The world of religious institutions is more complex than it seems at first glance. For a layman, everything is reduced to regular clergy (those governed by a monastic rule) and secular clergy (independent priests and deacons), but then each one is subdivided into various types of institutions. Of these, for example, there are two:orders and congregations , the latter being able to be clerical or lay. We are going to stay with the laity in this article to focus attention on a specific one, that of the Celite or Alexian Brothers , because his occupation was as specific as it was curious.

Members of lay congregations did not pronounce vows solemn butsimple , so they were not priests. They normally focused their activity on teaching and catechesis, or in the care of disadvantaged sectors like orphans, sick poor and convicts. In the case of the Celite Brothers, the object of their services were the most extreme patients of the past, those whose contact could mean death:those affected by contagious diseases and most especially the plague.

It is convenient to put yourself in a situation and take into account that centuries ago, when a pandemic broke out, little could be done more than isolate those affected waiting for it to go away on its own, which often happened because the mortality rate was so high that the chain of infection was interrupted or hindered. Meanwhile, the dying were forced to cloister themselves in their homes or were expelled outside the urban perimeter, considering them evicted without receiving care .

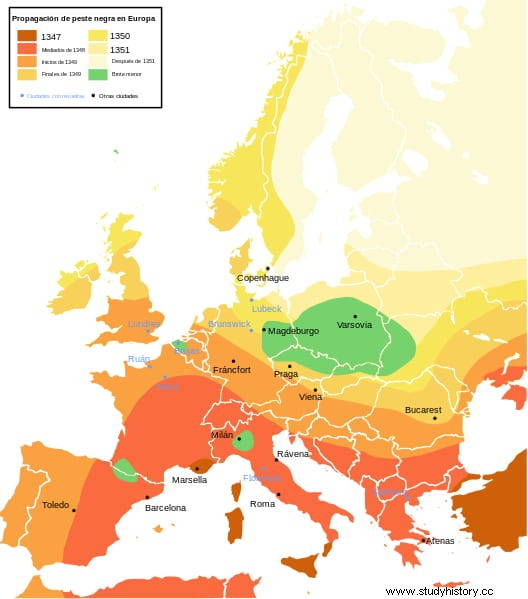

In that sense, the so-called Black Death It was one of the critical moments in European medieval history. Identified today with the bubonic plague , which was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread through the bite of fleas that rats had, it appeared in the West in the fourteenth century, more specifically in Italy, thanks to the trade routes that came from China. Its maximum severity occurred over almost two decades between 1346 and 1361, causing at least the death of a third of the population (although some authors raise the percentage to two thirds), which in round numbers would mean fifty to eighty million corpses.

An impressive amount that reveals a serious problem:getting rid of those bodies in a context in which hardly anyone wanted to approach them, something even worse when it came to living patients. In this context, some religious orders or institutions were created - at that time it was faith that catalyzed helping others and charitable work - aimed at addressing the issue.

For example, the Brotherhood of Charity of Toledo , as its name indicates, from the 11th century onwards it founded numerous hospitals from which it developed an intense activity in favor of neighbors without means , such as medical care, feeding the hungry, maintenance of orphans and widows, ransom payment of prisoners, etc. It was quite paradoxical that most of its members came from noble birth.

One of the activities of said brotherhood was shared with that of the Celites and consisted of taking charge of the burial of deceased in unusual circumstances , such as drowned without identity, executed, murdered foundlings, sick without means, etc. In other words, all those who, for whatever reason, could not be buried normally.

Likewise, they also took care of something as important at that time as saying masses for their souls; a priori It may seem inconsequential but, spiritual issues aside, the fact is that these trades -as well as the burial work- had to be paid for and that was what they dedicated part of the alms they collected.

The Celites, a word derived from the Latin cella (alluding to the cells or small rooms where they lived), also known as Alexians (for his patron saint, San Alejo) or medaños (by its founder, Meccio), were made official in a process that began in 1460 and concluded in 1476 signed by Sixtus IV, although they existed de facto from at least a century before, as a branch of the Beghards (the male version of the famous beguines).

Although they were laymen, they were governed by the Augustinian rule and took their first steps in Brabant (Flanders), spreading throughout central Europe . Because of the hymns they sang at funerals, they were often confused with Lollards and other heretics, which is why Pope Gregory XI had to issue regulations to protect them.

Currently, the Celite Brotherhood still exists, although limited to Germany, Belgium, the United Kingdom and the United States. Many of its members have professions related to health and work in the hospitals that they manage on a non-profit basis, where there are no longer plague patients but other contemporary ills have arisen. (AIDS, alcoholism, drug addiction, psychiatric illnesses, senile dementia, homelessness...) that give patients this marginal status that has traditionally required your attention.