There are already several articles that we have dedicated here to the First Punic War. At least two of them, the one that deals with the battle of Cape Ecnomus and the one that reviews the history of the mercenary general Xanthippus, focus much of the attention on the Sicilian scenario and make contextual reference to a specific confrontation that largely determined the subsequent events:the long siege of Lilibea (Lilybaeum), which lasted almost a decade.

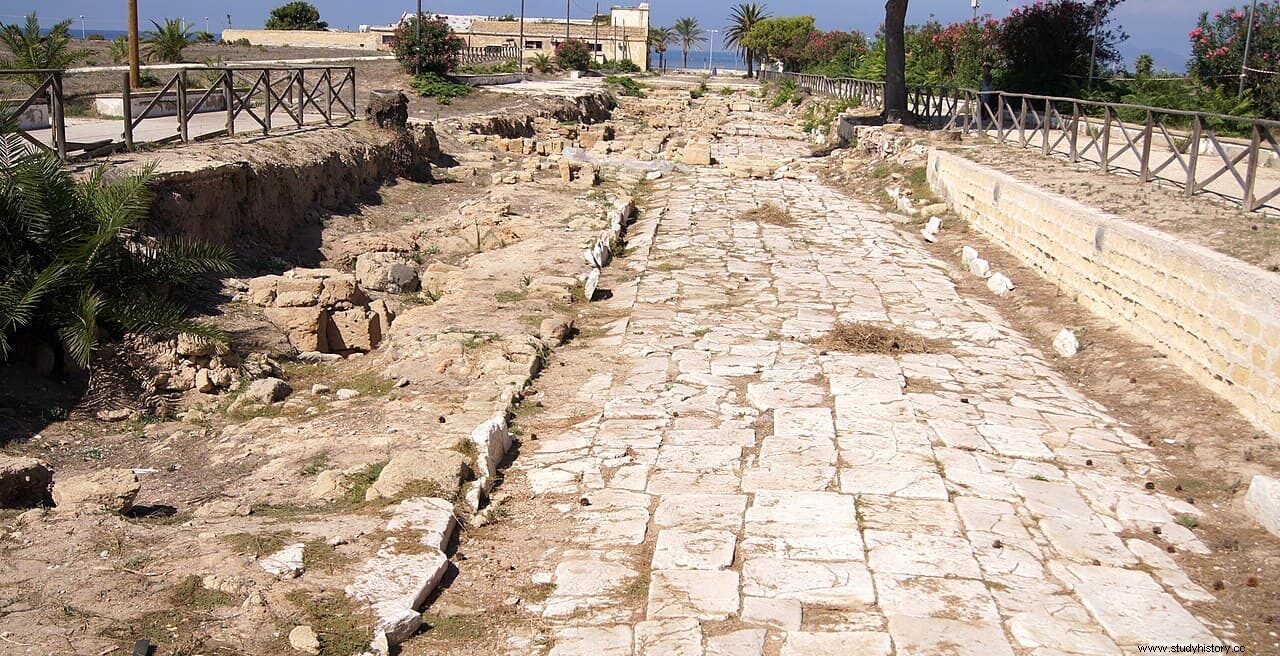

Lilibea is the name given in ancient times to the current Italian municipality of Marsala, located in the province of Trapani in Cape Boeo, which constitutes the extreme western Sicilian and therefore the closest point to the African coast (to Tunisia, for greater accuracy).

Today less than eighty-five thousand inhabitants live there, conserving a considerable monumental heritage from the 16th century left by the Spanish, but there is also archaeological evidence of an earlier era.

We are referring to Motia, the first Phoenician colony, established on the neighboring island of San Pantaleón and destroyed at the end of the 4th century BC. by Dionysius I, tyrant of Syracuse, who caused his people to move to Cape Lilibea and found a new settlement helped by the Carthaginians. This is how Lilibea was born, which was endowed with strong fortifications because its strategic location made it foreseeable that it would arouse the greed of others. This would happen in the year 276 BC, when Pirro, king of Epirus, laid siege to the city in his campaign to dispossess Carthage of the Sicilian land.

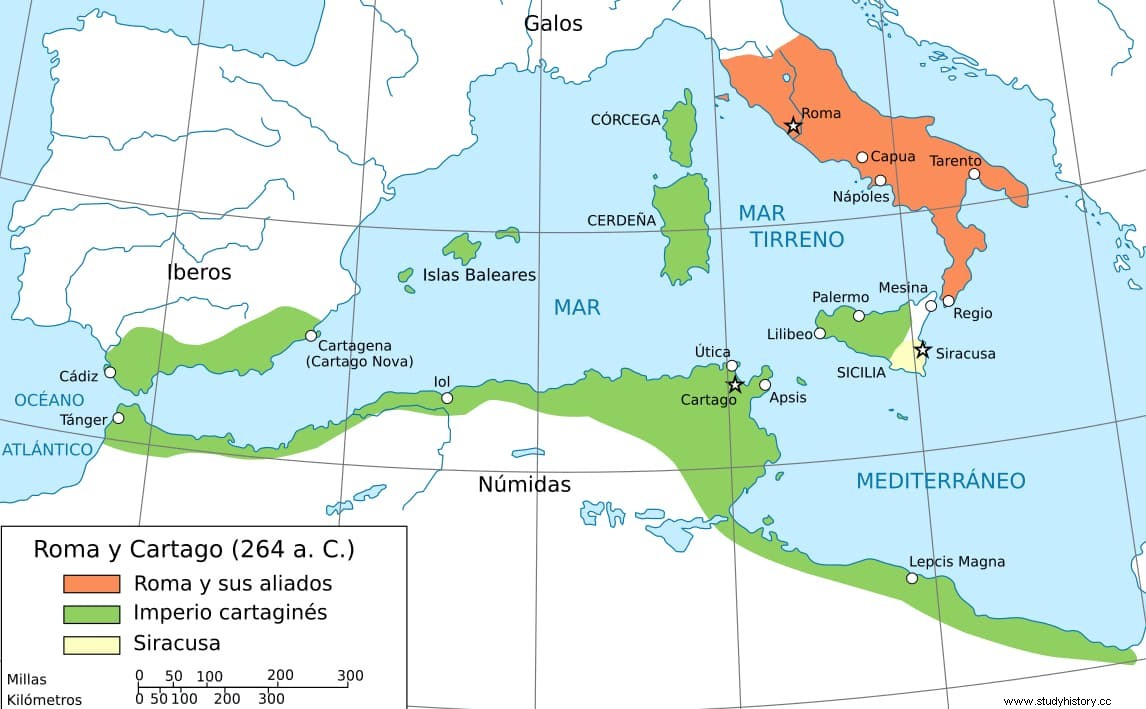

It was unsuccessful. Lilibea resisted receiving supplies by sea and Pyrrhus had to lift the siege two months later. However, that did not mean a return to calm because a dozen years later the Carthaginians found themselves with a new enemy:a Rome in full expansion to the south that had already managed to take over the entire Italian peninsula and was now making the leap beyond the seas, entering into an inevitable collision with Carthage, the power that until then dominated the western Mediterranean, with territories in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, Corsica, Sardinia, the Balearic archipelago... and the western half of Sicily.

In fact, the control of that island and its resources passed through taking over the city of Messina, something that the Romans carried out under the pretext of meeting the request for help sent by the Mamertine mercenaries who had occupied it for Syracuse. It soon became clear that the ensuing war was going to be long and costly, and it could not be decided in favor of one or the other contenders with a decisive battle but rather through attrition.

And, a priori , Carthage had the advantage of its powerful fleet, which allowed it to keep the front far away, guarantee the continuity of trade and face the conflict with mercenaries.

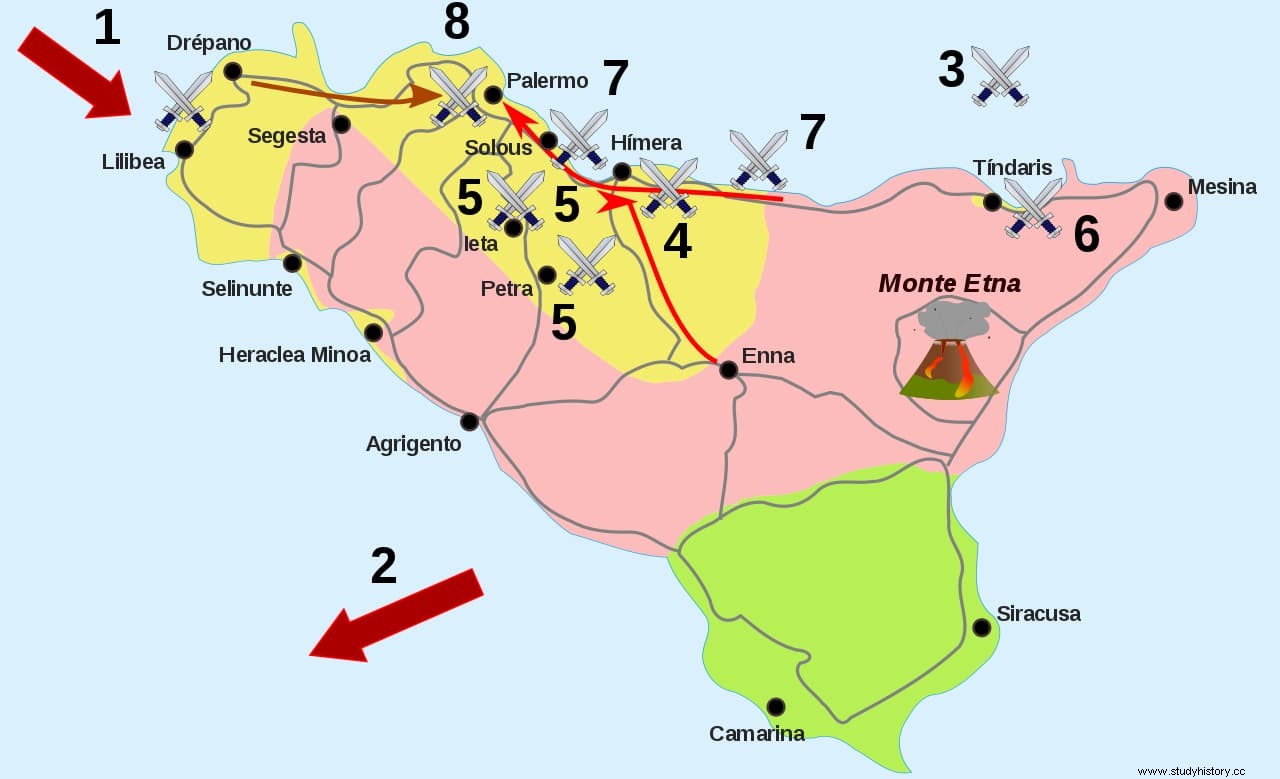

The exchange of blows brought different luck to each other. The Carthaginians Aníbal Giscón and Hannón suffered unexpected defeats that Amílcar (not to be confused with Barquida) later alleviated, and although little by little the Romans managed to gain a foothold in Sicily to continue operations, things came to a standstill. In 260, Rome understood the importance of gaining control of the sea and undertook the construction of a large fleet, ironically inspired by the enemy, with which it tried to conquer the Lipari Islands.

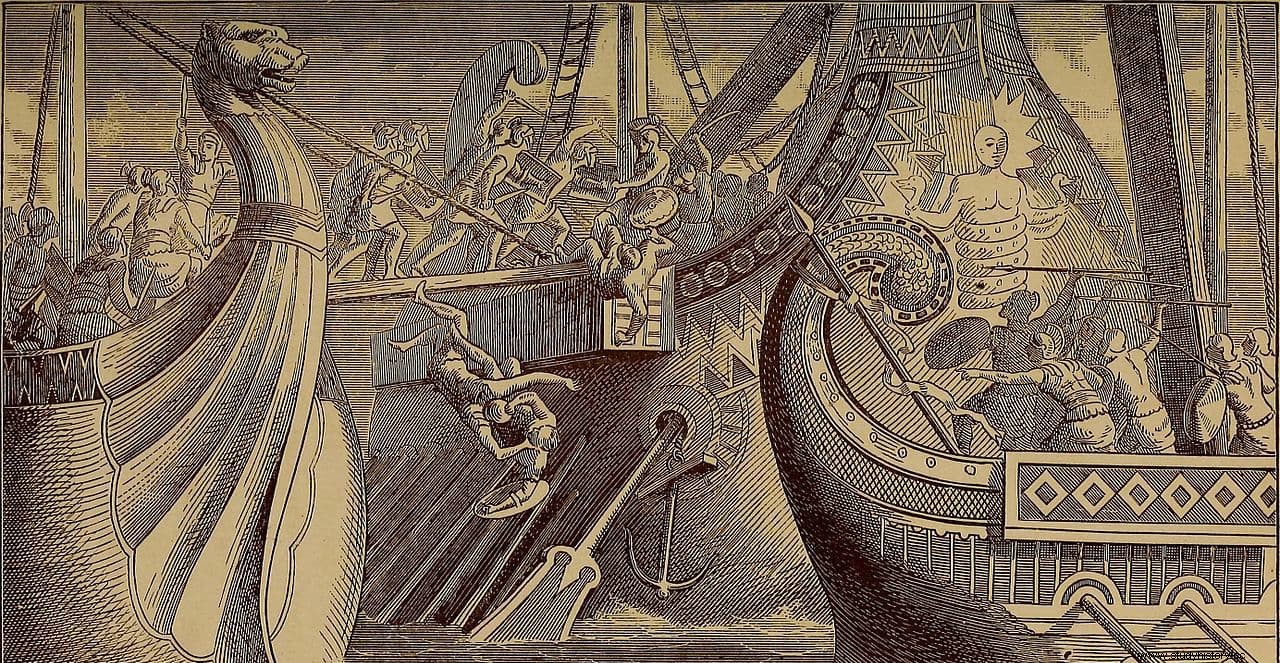

Aníbal Giscón inflicted a severe defeat on him, making it clear that having ships was not enough; The result of this, the lesson learned, was the incorporation of the corvus to minimize the seafaring skill of the Punics and favor the action of the embarked legionnaires. The victories of Milas and Sulci proved the correctness of the strategy, and both the Lipari and Malta passed into their hands. Then, the decisive victory at Cape Ecnomus allowed them to set foot on African soil and take the front line there, in the final phase of the war.

In all of this, the evolution of the operations in Sicily was decisive. The legions were taking Akragas (Agrigento), Panormus (Palermo), Ietas, Solunte, Petra, Tíndaris, Selinunte and Heraclea Minoa, pushing and cornering the Carthaginians in the westernmost part of the island. There, what seemed to be the last nucleus of Punic resistance was organized around the walls of Drépano (Trapani), to the north, and Lilibea, to the south, which were separated by barely forty kilometers. For now, however, the Romans turned their attention to the latter. It was the year 250 BC.

With the mission of conquering it, the consuls Cayo Atilio Regulo and Lucio Manlio Vulsio received four legions that, together with the auxiliaries, totaled nearly one hundred thousand men, to which a fleet of two hundred ships had to be added. Opposite the Carthaginian Himilcón had entrenched himself with seven thousand infantry and seven hundred horsemen, most of whom were not Punic but Greek and Celt.

The numerical disproportion was compensated by the effective defensive system, based on walls, towers and a huge moat that, as we saw, had already caused the failure of Pirro.

But, although the proverbial Roman war engineering managed to overcome these obstacles, filling in the moat, installing siege machinery (catapults, battering rams...) and demolishing several towers, the possible departures of the defenders to hinder the work and the inevitable appearance of epidemics among the besiegers caused the situation to drag on with no end in sight. Only discouragement made several of the mercenaries desert, forcing Himilcón to promise them financial prizes to prevent the example from spreading.

The two consuls ordered the enemy positions to be assaulted several times, but to no avail, and soon after, a fleet awaiting its opportunity hidden in the neighboring Aegadian archipelago rushed into Lilybea with several thousand reinforcements and supplies. This was possible thanks to the fact that the city had a port that was difficult to access, in which a pilot was needed to cross the sandbanks, and the Romans did not dare to pursue them for fear of running aground.

With those reinforcement troops, Himilcón carried out a night sortie. He did not achieve his purpose of surprising the adversary and the latter, understanding the danger that that open port posed, sank several ships in front of the mouth to try to block it; it did not work either, since the Carthaginians then used light galleys, whose veteran crews evaded the Roman efforts to intercept them. And so, that tug-of-war threatened to entrench itself forever; if the legionnaires knocked down one wall, the Punics built another; if they got too close to breaching, a quick exit prevented it.

As was the case historically in sieges, there were times when the besiegers were worse off than the besieged. The ships provided fresh food to Lilibea while the legions suffered from insufficient supplies. Above, a strong gale blew away the roofing of the battering rams and siege towers, rendering them temporarily unusable; somewhat aggravated by another audacious action by Himilcon, who took advantage of that strong wind to set fire to much of the Roman camp.

The Romans decided to build palisades of earth and wood to protect them from those exits, although that meant having to partially give up a direct assault on the city and surrender it by starvation. With that objective, the new consuls, Publio Claudio Pulcro and Lucio Juno Pullo, concentrated their attention on Drépano, defended by general Aderbal.

This posed to his mercenaries a dilemma:endure a long siege or fight a battle to heads or tails. They opted for the latter, embarking to deal with the mighty Roman fleet Pulcrus had sent to cut off the sea supply line to Lilybea.

The clash ended with a resounding Carthaginian victory, which allowed Aderbal to send his squad under the command of Cartalón to the aid of the city, against the Roman ships that were blockading it. The Punics triumphed again, to the misfortune of Pulcro who, according to tradition, was sentenced in Rome to pay an enormous fine for not having heeded the bad omens:the sacred roosters of the oracle had refused food and he threw them into the sea to the cry of "If they don't want to eat, let them drink!" .

That same 249 B.C. Amílcar Barca arrived in Sicily to take command (yes, Hannibal's father), who began a series of guerrilla activities that drove the Romans crazy for three years and allowed him to occupy the city of Erice, besieging the enemy garrison on the homonymous mount that served as a sanctuary of Venus while the city itself was surrounded by the legions. These, however, were limited when it came to moving to control the Punic.

Exhaustion was beginning to take its toll on each other; the terrible number of dead and wounded prevented there from being sufficient replacements to cover the casualties and the economy of both powers was sunk, as agricultural work and, above all, commerce were interrupted. Still, in 243 B.C. the Roman Senate managed to raise private funds to build a new fleet and Carthage, seeing the danger, did the same soon after. The common idea was to wage a battle that would definitely tip the scales to one side or the other.

The two fleets met in May 241 BC. in the aforementioned Aegadian Islands, where the two hundred quinqueremes of the consul Cayo Lutacio Cátulo demonstrated that they had already acquired a seafaring skill comparable to or superior to that of their rival, to the point that they even dispensed with the corvus .

Hanno the Great , defeated at Cape Ecnome, returned to bite the dust (water, in this case) despite the fact that he had fifty more ships than Catullus, since he did not have enough sailors for them and those who did lacked adequate training .

Therefore, that naval battle was the end in every sense:for Lilibea in particular it meant not being able to continue receiving supplies, and for Carthage in general it meant being left without a war fleet, because in the time it took to build another the enemy could act. at pleasure The Carthaginian senate ordered Hamilcar Barca to negotiate peace, but he refused, considering that his position in Sicily was still strong. Then he was relieved by Giscón (not Hannibal Giscón, who was said to have been crucified by his own men after being defeated in Sardinia, but another), who had replaced Himilcón at the head of Lilibea.

Giscón was in charge of signing the Treaty of Lutacio, by which the Carthaginians had to cede most of the islands of the western Mare Nostrum (Sicily included), return the prisoners of war and pay a high compensation of two thousand two hundred talents in ten years. , plus another thousand immediate. Of course, Lilibea passed into Roman hands, although time was granted for all the soldiers who were in Sicilian territory to be evacuated by sea. From port of entry to port of exit; difficult to find a better metaphor for the end of the First Punic War.