We have already devoted the odd article to certain mysterious radio broadcasts consisting of the same message (buzz in one case, numerical codes in another). Today we are going to tell about another case in which the same song was broadcast on a loop for three days in a row, sowing confusion among listeners. Only this time the mystery was solved after that time:the objective was to deplete the batteries of mines controlled precisely by radio. It happened in Finland in 1939 and the music in question was a very popular folk song:the Säkkijärven polkka .

Although it is often believed that etymologically it refers to Poland, in reality the polka is a type of dance -and the music that goes with it- originally from Bohemia, where it was born in the second quarter of the 19th century, deriving from the Czech term půlka , which means "half" and alludes to the short (medium) steps of their dance. In fact, it is believed that its creator, the music teacher Josef Neruda, had the idea in 1830 when he saw a student of his, named Anna Slezáková, dancing to a popular song (specifically, Strýček Nimra koupil šimla , translatable as "Uncle Nimra bought a white horse") more lightly than normal.

And it is that the polka, with a two-four beat, is of fast movement, which was so groundbreaking in its time that it made it spread immediately throughout all European countries, jumping to the USA in 1844 and becoming the most popular ballroom dance. successful until the late nineteenth years (even John Ford reflected it in Fort Apache , in the NCO dance scene, with Henry Fonda in the lead). But it also caught on in the academic field, so that composers such as Smetana, Strauss, Shostakovich or Stravinsky incorporated polkas into their repertoire. However, the author we are interested in here is less well known:the Finn Viljo Vili Dressing.

Vesterinen was born in 1907 in what was once Terijoki, a city renamed Zelenogorsk today because it is part of the Russian oblast of Leningrad, since it is located in one of those hot border areas (that is to say):the Karelian Isthmus. Therefore, he has been changing hands and if he belonged to Finland - which in turn was part of Sweden - until Peter the Great annexed it to the Russian Empire in 1721, returned to Finnish hands in 1811 but integrated into the Grand Duchy of Finland, which had been in the hands of the tsars since Alexander I conquered it in 1809 to make it a buffer state against the Swedes, albeit granting it ample autonomy.

Alexander III and Nicholas II carried out a Russification campaign in the duchy, appointing a governor and imposing their language. In 1917, taking advantage of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Finns declared their independence, which gave way to a civil war between reds and whites, parallel to what was happening in the neighboring country. The latter prevailed, consolidating the new state and establishing a constitutional monarchy with a German on the throne, Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse-Kassel, without a parliament and related to the German Empire. The latter's defeat in World War I paved the way for a democratic republic from 1918.

That was the historical context in which Vesterinen had to live. Pianist, cellist and accordionist, he began recording in 1929, and would enjoy success and fame until his death in 1961 due to alcohol and tobacco. Earlier, he composed some of the most popular national melodies, of which the aforementioned Säkkijärven polkka should be highlighted here. , since it was the theme that was played incessantly on that radio in a year of such warlike resonances as 1939:as almost everyone knows, in September the Second World War broke out; but three months later the so-called Winter War also began.

That last dispute pitted Finland against the Soviet Union when the Moscow government demanded the cession of the border region between the two in exchange for territorial compensation elsewhere. The reason? The border was too close to Leningrad, about thirty kilometers away, which was a problem for his security. Obviously, Helsinki, which in addition to being in a moment of economic growth was experiencing a moment of passionate pan-Scandinavian romantic nationalism, refused.

In reality, the Finns had crossed that border more than once trying to attract peoples of their ethnicity and culture in the Russian zone, aspiring to create Greater Finland, an idea proposed in the interwar period that sought to unite in the same state Finns, Sami, Karelians, Estonians, Kvens and Ingrians; Similarly, the Soviets had also infiltrated Finland, supporting its Communist Party and organizing revolutionary attempts that led to the outlawing of communism in 1931. In other words, relations were not exactly cordial.

Even so, from the spring of 1938 Stalin tried to reach an agreement that would safeguard the protection of Leningrad against the potential enemy that was becoming more and more powerful in Europe, Nazi Germany; especially considering Finnish philo-Germanism. But neither the Soviet request for the cession of islands in the Gulf or the Hanko Peninsula for a limited time, nor the request to move the borders of the Karelian Isthmus some thirty kilometers -to the vicinity of Viipurí (present-day Víborg)-, in exchange for hand over eastern Karelia (twice what they asked for), were accepted by Helsinki, which in its counteroffer raised the handover of Terijoki and the islands, considerably less than what Moscow wanted.

The negotiations ended in failure in November and on the 26th of that month, the death of several Soviet border guards - an alleged false flag operation - gave Moscow a casus belli to start what is known as the Winter War. Counting on the peace of mind that the recent Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact (signed in August) gave him for the time being, Stalin ordered the Red Army to enter Finland; his military commanders calculated that the campaign would last two weeks, given the success of the invasion of eastern Poland and the one charged against the Japanese in Khalkhin Gol (Manchukúo). However, things turned out very differently.

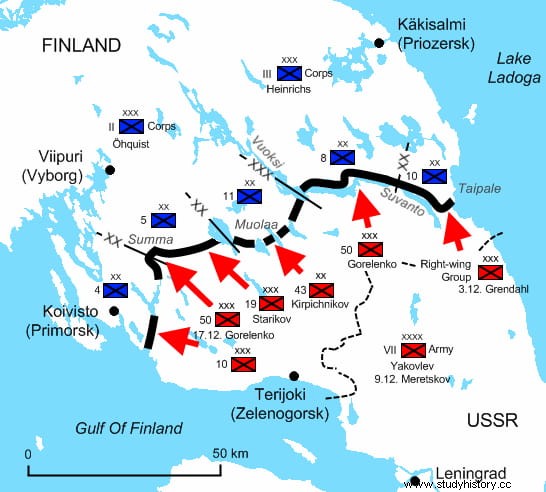

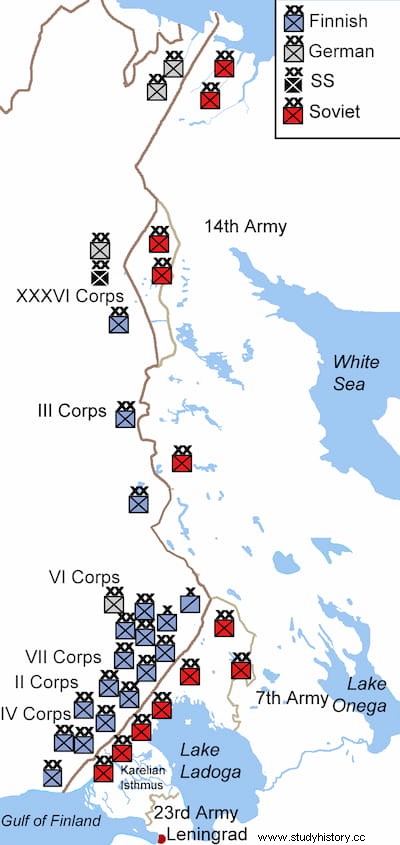

Finland was a very young country and, therefore, practically lacked the road infrastructure to advance through a terrain that, to a large extent, was made up of forests and lakes, to which snow and swamps had to be added, all of which was to be one more weapon of his soldiers. Hence the enormous superiority in number of troops destined by the Soviet commands to compensate:twenty-one divisions against eight. In a lightning attack, they occupied Karelia and set up a sympathetic government, while the Finns withdrew to the Mannerheim Line, a defensive system with more than two hundred strong that crossed the isthmus from east to west.

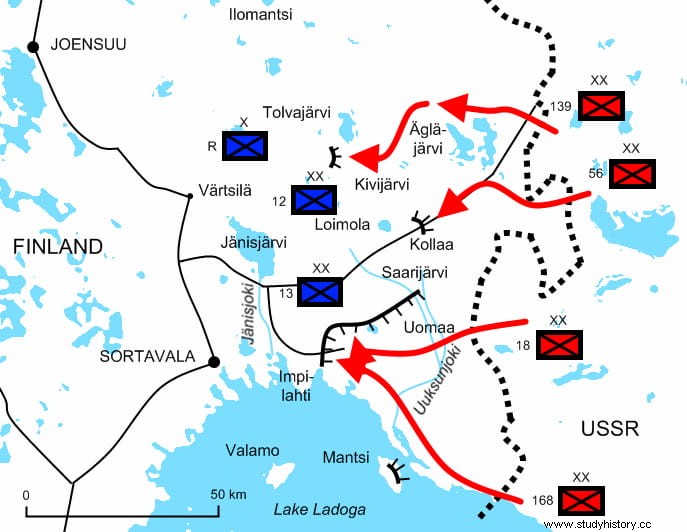

The line held, but lacking anti-tank material, little ammunition and often without even uniforms, they opted for a guerrilla war that had a good ally in the intense winter cold. Something that was evident in the combats of Lake Ladoga and Kainuu, where some snipers also showed off, while in Lapland, the Soviet advance stalled in the snow. Three weeks later there were hardly any changes, so Stalin replaced Marshal Klíment Voroshilov with Semyon Timoshenko, who decided to focus operations on Karelia after receiving reinforcements.

The change in tactics included ending the massive charges of men and tanks, or at least protecting them with smoke and artillery fire. The fortresses were falling and the Finns, who caused heavy casualties to the enemy but, in turn, were very depleted, made a second withdrawal. The Helsinki government found itself alone as it did not receive the expected support from Sweden and only had a Franco-British expedition that, it was obvious, would not arrive on time, given that the Swedes and Norwegians were not going to give them way. He understood, therefore, that he could do nothing but negotiate with Moscow (which, in turn, saw how her country was expelled from the League of Nations).

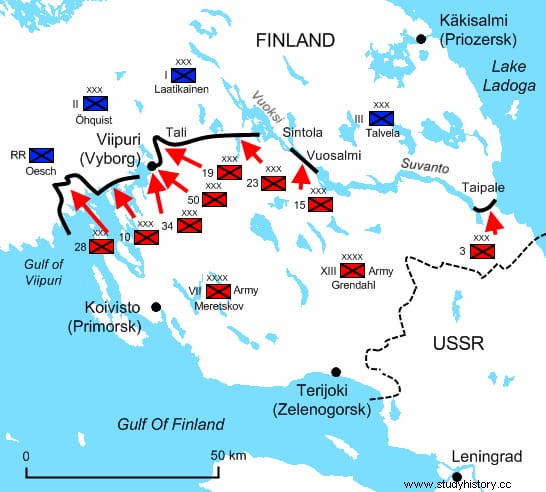

Initially he did not get a response, since the Red Army had reversed the situation and was advancing the front line more and more, surpassing the Mannerheim Line and occupying Viipurí (Víborg); Let the reader keep this name, which we will see again later. Later he did listen to the armistice offer, but demanding more concessions than before. Finally, on March 12, 1940, the Moscow Peace Treaty was signed, by which Finland handed over the Karelian Isthmus and the northern region of Lake Ladoga, which was equivalent to eleven percent of the country, a good part of its territory. more industrialized, as well as an area of Salla, the Rybachy peninsula and four islands in the gulf. Likewise, the Hanko Peninsula was leased for thirty years. The Soviet Union returned the Petsamo region, which it had conquered in the war.

But things weren't really over. Fifteen months later, in June 1941, he finished what is called Välirauha ("Temporary Peace") and a second contest broke out, called a Continuation for obvious reasons. Of course, the panorama was substantially different, since the world conflict had reached unsuspected dimensions and the United Kingdom, along with other Commonwealth states, declared war on Finland on December 6. The Nordic country was not daunted and took advantage of Operation Barbarossa (German invasion of the Soviet Union) to try to recover what was lost.

In fact, he was not content with that and captured East Karelia as well, linking up with the German army some thirty kilometers from Leningrad. Together, they tried to seize Murmansk, without success. The fact is that the Germans, who had provided military equipment to their occasional allies in exchange for passing through their country to the north of the Soviet Union, soon realized that they were only interested in their territorial strategic ambitions. The Soviets then launched a counteroffensive that stabilized the front. It was already 1942 and the German defeat at Stalingrad made Helsinki rethink things.

Aid to Germany had been strongly opposed, which has now regained strength, so the government asked Moscow to negotiate peace by returning to the status quo of the previous treaty. As in the previous conflict, Stalin did not respond to the offer initially, but in practice the Finns refused to enter into an open alliance with the Germans. During the following year, the situation did not change much, until in December, at the Tehran Conference, Roosevelt convinced Stalin by offering the support of the Allies to the conditions that he put.

These were harsh, after the signing of the Moscow Armistice on September 19, 1944; They included the disarmament of the German troops in Finland, which would mean a war with them in Lapland and a return to the pre-war borders, although the Finns had to cede the mining municipality of Petsamo (now Pechega, rich in nickel) and the lease of the Porkkala peninsula, in addition to paying compensation of three hundred million dollars.

Such was the historical context. Now we have to go back to August 28, 1941, two months after the start of the Continuation War, when the Finnish army, in its vigorous offensive, forced the Red Army to withdraw from Viipuri. Let us remember that it is the current Russian city of Víborg (not to be confused with the Danish one of the same name), a port enclave in the Baltic that today continues to maintain a close link with Finland -it is a weekend tourist destination-, taking into account that forty thousand Finnish inhabitants had had to abandon it at the end of the Winter War.

Well, the Soviets left several minefields around the urban area to protect their retreat. These were not conventional mines but radio-controlled mines, activated by emitting a chord of three musical notes on the tuned frequency ad hoc and exploding when said sequence is played. This peculiar system left the Finnish soldiers disconcerted, who at first thought that it worked through a clockwork system, since explosions occurred without apparent logic. Later, the discovery on a bridge of an explosive device that worked in the same way, opened the eyes of its technicians.

The bomb was sent to Helnsinki for engineers to analyze, discovering that the mines had three sound sensors that, upon receiving the three notes at a certain frequency, activated them. To fix this, a REO 2L 4 210 Speedwagon truck was dispatched equipped to transmit music on the same frequency, so as to interfere with Soviet broadcasts. The theme chosen was, as we said at the beginning, Säkkijärven polkka , for no other reason than the fact that the vehicle was carrying a record whose repertoire included that song, in a version recorded by the aforementioned Viljo Vesterinen. At least in theory, since Viipurí was in the region that the Norse called Säkkijärvi and the coincidence seems very coincidental.

Thus, on September 4, 5 and 6, an unusual musical battle broke out, with the Soviets issuing their code and the Finns fighting back with the polka. It was seventy-two hours of uninterrupted music that led listeners who tuned in to that frequency to think that the radio programmers had gone crazy. On the third day a second truck arrived, coinciding with the discovery that the enemy was beginning to broadcast from two more frequencies. This forced the car's transmitters to be reinforced and the duel on the airwaves continued for another month, until on February 2 it was calculated that the mines had exhausted their batteries.

And so ended one of the most unusual battles of World War II. As one verse of the song says:“Säkkijärvi se meiltä on pois, mutta jäi toki sentään polkka!” , which means "We have lost Säkkijärvi, but we still have the polka!".

Fonts

VVAA, Finland at War. The Winter War 1939–40 | VVAA, Finland at War. The continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45 | Allen F. Chew, The White Death. The epic of the Soviet-Finnish Winter War | Tiina Kinnunen and Vile Kivamäki (eds.), Finland in World War II. History, memory, interpretations | Olli Vehviläinen, Finland in the Second World War. Between Germany and Russia | Wikipedia