A few days ago we published an article in which we saw how, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, Czechoslovakia disintegrated between internal centrifugal movements (which gave rise to the Slovak Republic) and the scrapping to which Germany and Poland subjected it, the same year in which Hungary recovered a region called Transcarpathian Ruthenia. The curious thing is that, compared to the others, the Magyar government was of a very different nature since in 1919 the Hungarian Soviet Republic had been proclaimed.

The end of World War I brought a lot of changes to Europe, and since the Austro-Hungarian Empire was on the losing side, it got to experience some even before the Treaty of Versailles.

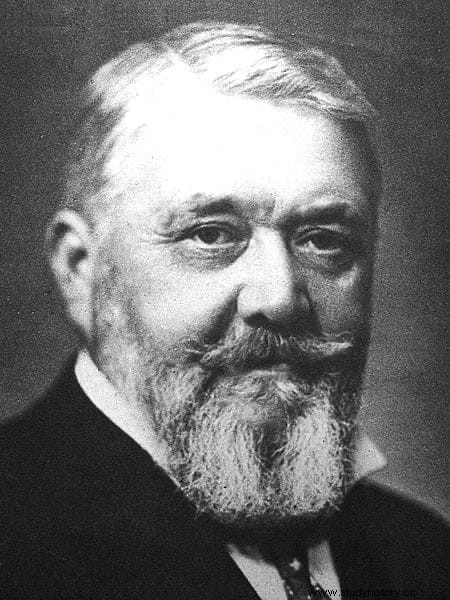

On October 30, 1918, the troops refused to fire when a coup by the soldiers' associations overthrew the government of János Hadik, who had been in power for barely a day, and forced the emperor to accept the presidency of the social democrat Mihály Károlyi. .

Károlyi was the leader of the so-called National Council, an alliance of the Social Democratic and Radical parties that five days earlier had published a manifesto demanding, among other things, the end of the alliance with Germany, the country's independence from the empire, the liberation of political prisoners, agrarian reform and the calling of free elections with universal suffrage and women's votes.

Hadik took the troops out into the streets to break up the demonstrations but was met with disobedience from him in what has gone down in history as the Chrysanthemum Revolution.

It was relatively bloodless - although the soldiers assassinated the emperor's representative, Count Estaban Tisza, whom they hated as responsible for leading them to war - and the result was dubbed the Hungarian People's Republic, proclaimed on 16 November.

Once at the head of the executive, the National Council fulfilled its promise and separated from the empire but was unable or unwilling to do the same with the other points. Thus, he proclaimed universal suffrage but without calling elections and the country's catastrophic economic situation resulting from the war continued without a solution, especially when the long-awaited agrarian reform did not develop as expected either.

In reality, as is often the case, Károlyi did not have much room for action and could not risk having the conservative army commanders or some key figures in the administration against him, always wary of excessive reforms. Nor did he have the support of the Triple Entente (the coalition made up of France, Great Britain and Russia), which did not even recognize the new regime despite signing the Belgrade Armistice with it, which was supposed to regulate the disputed borders.

In an attempt to guarantee order, the soldiers were massively discharged. Unfortunately, this, added to the more than 400,000 deserters and 725,000 prisoners of war released by the Soviets, meant nearly a million and a quarter more citizens who suddenly found themselves in civilian life without employment or means of support. Along with large sectors of the peasantry, they formed the basis of the new PCH (Hungarian Communist Party), founded on November 24.

Despite not yet having many militants, from the beginning he set the revolution as a goal, acquiring the weapons that the German army was delivering to equip his growing cadres and infiltrating unions and military councils, until then loyal to the National Council. And it is that the government was losing popular support by forced marches and weakening visibly:the ministers barely lasted a few weeks in office.

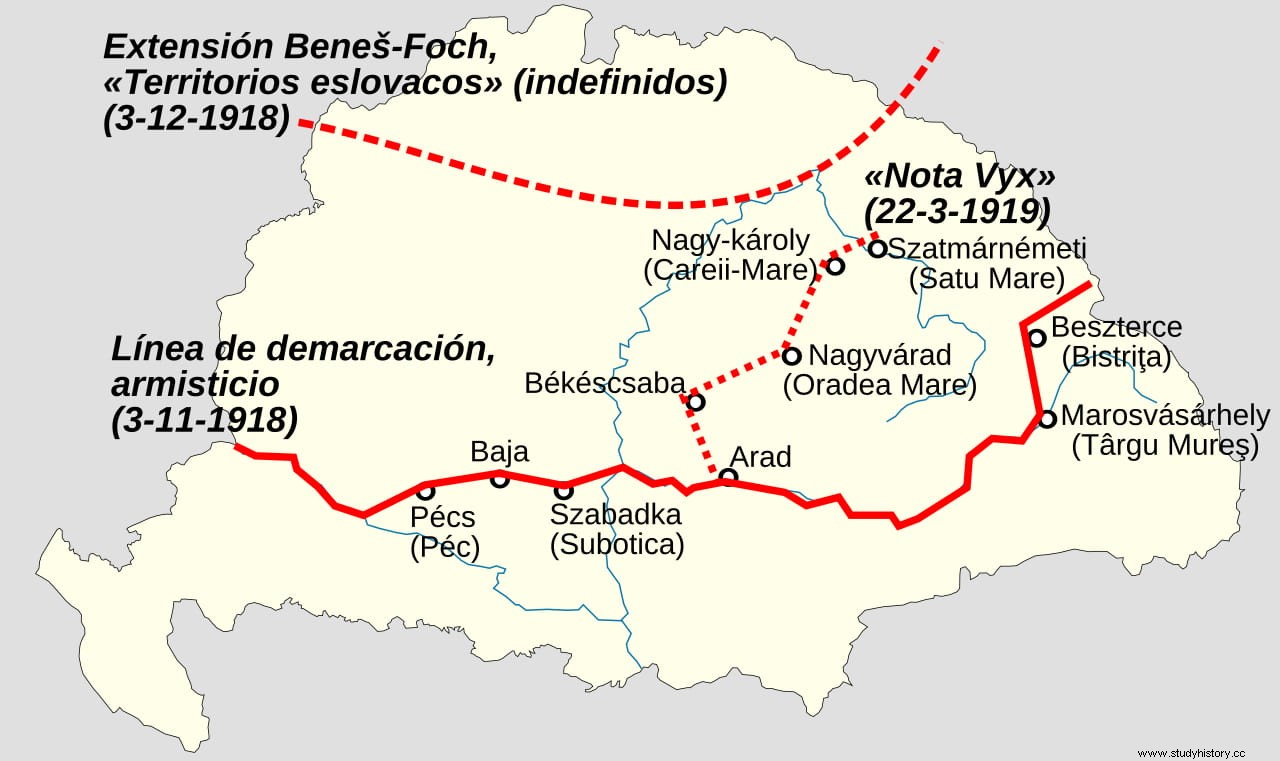

Another problem that it had to face was that of the claims of ethnic minorities, which could not be solved and ended with the loss of border territories when neighboring countries intervened to annex the parts that interested them.

Thus, taking advantage of the fact that the Hungarian army was in the process of disintegrating and, therefore, inoperative, the Romanians of Transylvania proclaimed their incorporation into Romania on December 1 and the armed forces of this country occupied the region. Yugoslavia had done something similar the previous month and Czechoslovakia also took over Ruthenia, which had a Slovak population, with the approval of the Triple Entente.

With the start of the new year, not only did the situation change nothing but it got worse and if the extreme left took to the streets to put pressure on, the right did the same, violently clashing, which led the government to ban the PCH and other extremist associations. In practice, that meant everyone against Károlyi, who on March 20, faced with the Romanian ultimatum that sought to appropriate more territory and having no forces to oppose, presented his resignation.

The government was left in the hands of a coalition of socialists and communists -with a majority of the former- under the leadership of Dénes Berinkey, a social democratic jurist who was first overwhelmed by some communist actions and then harshly repressed a mining strike, settled with a hundred dead. The two factions of the left became irreconcilable but the socialists were radicalizing their ideology to cushion the unstoppable defection of militants in favor of the PCH and their diminishing influence in the unions:nationalizations, tax increases, repression of counterrevolutionaries...

Public order was further undermined, with the councils exercising real power in the manner of the soviets in the face of government impotence. In addition, the timid economic reforms were insufficient to face the very serious situation of general precariousness and popular discontent led Berinkey to call elections for April 13. They were never held because the merged socialists and communists received power from a naive Berinkey, proclaiming the Hungarian Soviet Republic on March 21, 1919. Károlyi, who was still president, resigned.

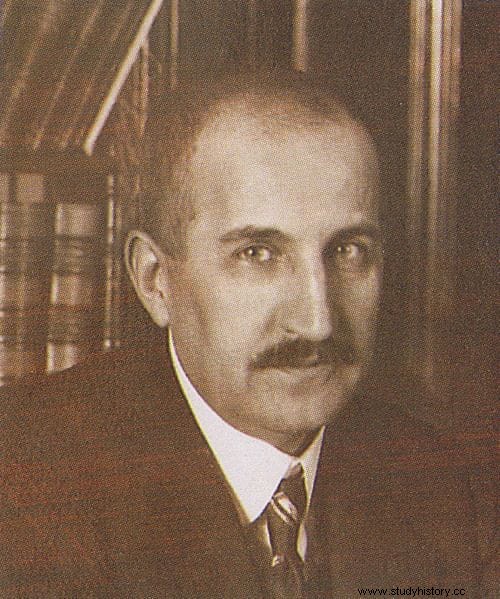

Although Lenin considered the implantation of a communist system in Hungary premature, given the archaic semi-feudal structures of the country, the truth is that the Russian and Spartacist examples inflamed the masses. The new party was led by Béla Kun, a lawyer, journalist and trade unionist, a militant of social democracy despite being from a bourgeois family; a war veteran who had fought on the Russian front, being imprisoned and embracing Bolshevism to the point that he joined the POSDR (Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, later reconverted into the CPSU) and collaborated with the soviets in the October Revolution. All that experience was later applied in his country, when he returned in 1918, ignoring Lenin.

And although he was imprisoned, he ended up assuming the Foreign Affairs portfolio in the new government, whose head was Sándor Garbai. This was a bricklayer who entered the leftist movements at a very young age and who was said to be only there to sign the sentences, since the real power was exercised by Kun. The policy applied was what was claimed:new constitution, rejection of the threats of the Triple Entente, elections with universal suffrage, free education, nationalization of services, industries, banks and large properties, and an eight-hour workday.

However, despite the abolition of private property, land was not distributed, provoking the anger of the peasantry. The fall in production, combined with the closure of businesses and the blockade decreed by European countries, led to a total shortage of supplies, with hunger spread at all levels despite the seizures made in the farms by patrols created ad hic . Coinage was then imposed, which led to considerable inflation.

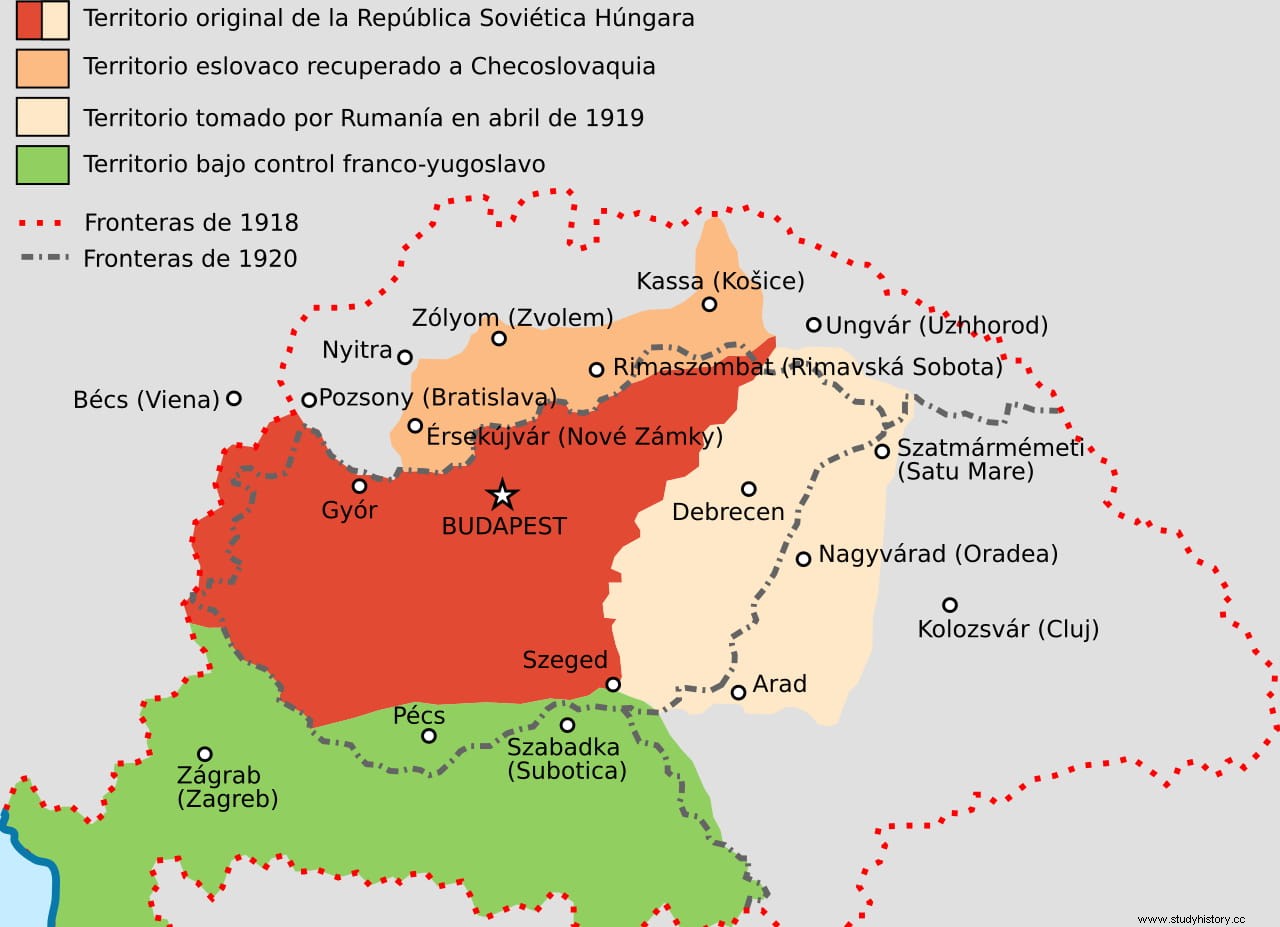

The poor economic management was not compensated by military success, despite the fact that not only were the Czechs stopped and pushed back, but Slovakia was taken and a Soviet republic created there as well. And it is that that victory was marred by new defeats against a Romania that was supported by the Triple Entente, due to the Transylvanian issue. But inside, things also went awry.

On June 20 there was an attempted coup by sectors of the anti-communist army. The reaction of the executive was implacable, instituting revolutionary courts and unleashing a persecution that became known as the Red Terror due to the hundreds of victims it claimed. The soldiers' councils were dissolved -the same ones that had facilitated the revolution- and martial law was established, which authorized summary trials in situ . All this earned the regime popular antipathy and nuclei of opposition began to sprout in border areas, as well as protests and revolts, especially in the countryside.

All these movements suffered from a lack of coordination, which is why, although they shook the government, it managed to hold on; yes, several socialist commissioners resigned, dissatisfied with his policy. More serious was the decision of the Union Board, voted and expressed on July 31, to stop supporting the communist system. This coincided with the final defeat against the Romanians, who were already threatening to enter Budapest, and the following day Kun finally resigned his post, leaving Hungary for Austria, which offered to take him in; On the way he was booed and attacked but he managed to get to Vienna.

He was replaced by Gyula Peidl, a socialist from the printers' union who had already been a minister under Károlyi. His cabinet was made up of social democrats and trade unionists but was in a very weak position because the Entente did not recognize him either, the people did not trust his announced democratization plan and the Romanian army was beginning to occupy neighborhoods in the capital. Even so, he adopted a series of measures that put an end to the communist adventure, whose sympathizers went underground.

Peidl's passage through the executive would be short-lived as he was deposed by the counterrevolutionaries, who agreed with the Romanian occupation forces. Like Kun, he had to take refuge in Austria while the reactionary István Friedrich succeeded him, while President Sándor Garbai was displaced by Archduke José, who arrived to assume the regency. Thus ended the Hungarian Soviet Republic… but also the Hungarian People's Republic. It had lasted a hundred and thirty-three days; in the end it turned out that Lenin was right.