On February 12, 1873, Amadeus I, the most democratic king that Spain knew in the 19th century, took his suitcases and undertook a trip to Portugal. Not without first making it very clear what he thought of the Spanish:

“If Spain's enemies were foreigners, I would be the first to fight them, but all those who attack her with the sword, the pen or the word are Spanish” .

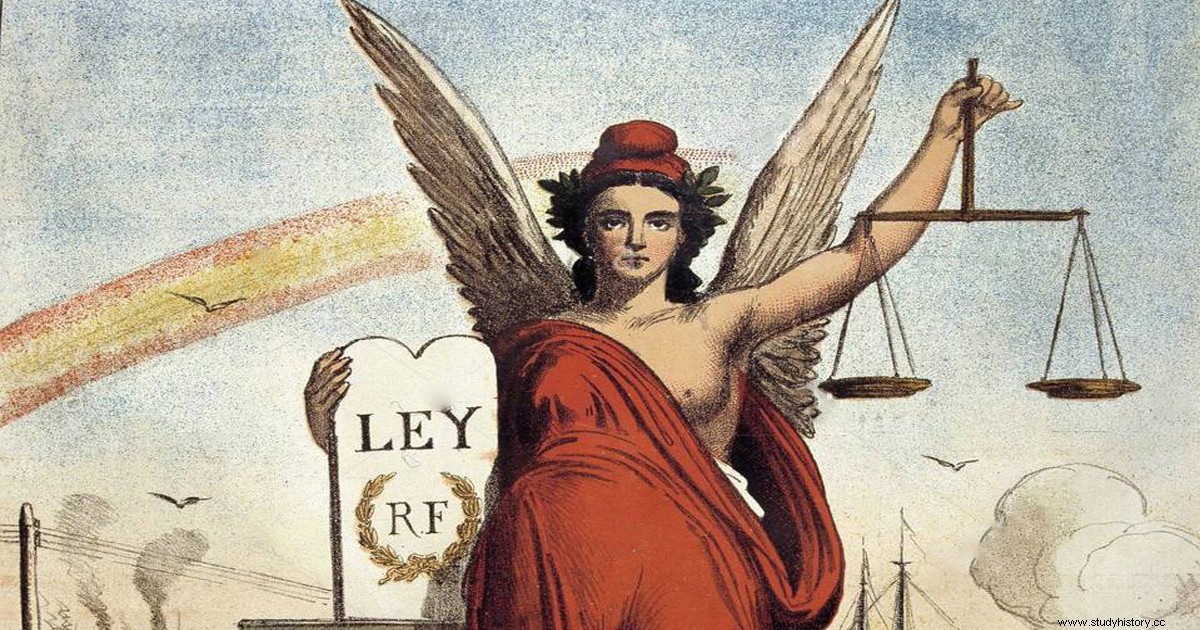

The day before, before the evident abdication of Amadeo I, the people of Madrid crowded outside the Cortes with liberal demands as their flag. Said renunciation of the throne was the opportunity that the heirs of the men who, in Cádiz in 1812, had drawn up one of the most advanced constitutions in Europe had been waiting for. It was time to put into practice the highest expression of political liberalism, by 258 votes in favor and 32 against, the Cortes on February 11, 1873 established the First Spanish Republic. 686 days later, the dream of the Spanish republicans faded, as they failed to politically impose themselves on the enemies that appeared from all sectors of society. By the way, as we will see, there is no worse enemy than the one you have at home.

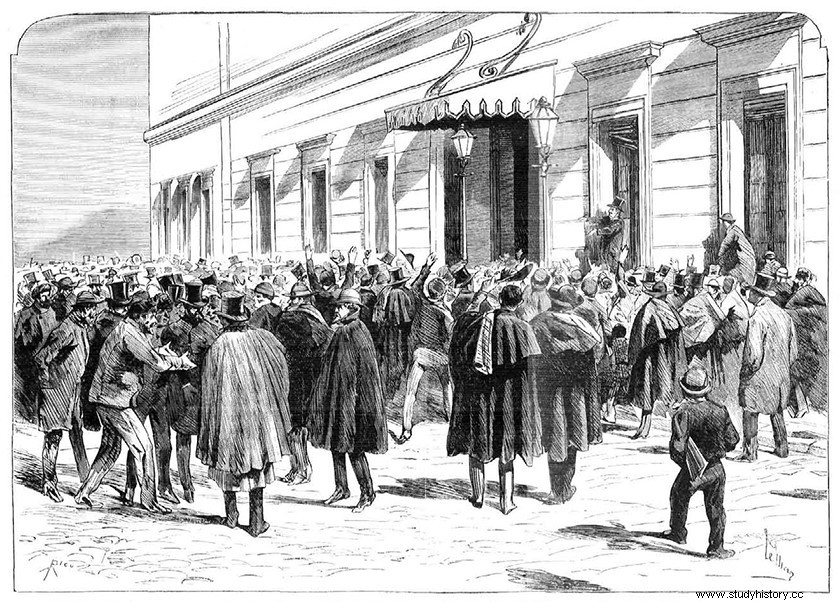

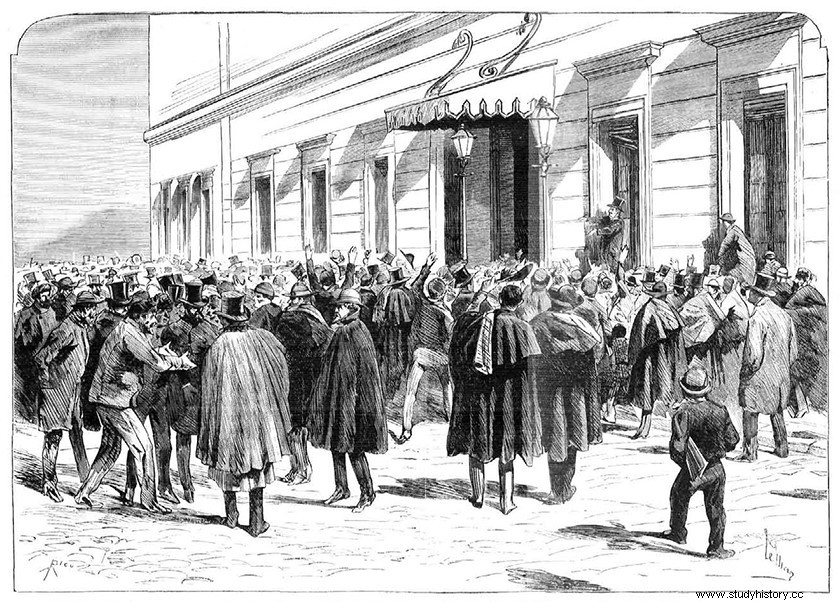

Exterior of the Cortes on February 10, 1873

The "enemy at home" thing seems obvious. Up to four presidents had the First Republic in less than a year. The first two Barcelonans; the lawyer Estanislao Figueras and the historian Pi y Maragall. The following two Andalusians; Nicolás Salmerón, from Almería, and Emilio Castelar, from Cádiz, by the way, the latter a member of the Royal Academy of History. Well, all of them took turns as ministers of the other cabinets, jumping from one party to another in a matter of days, they were members of the Progressive Party, the Democratic Party, or the Federal Republican Party, depending on the needs of each moment. It is evident that the lack of unity and direction led to a greater force for the enemies of the Republic.

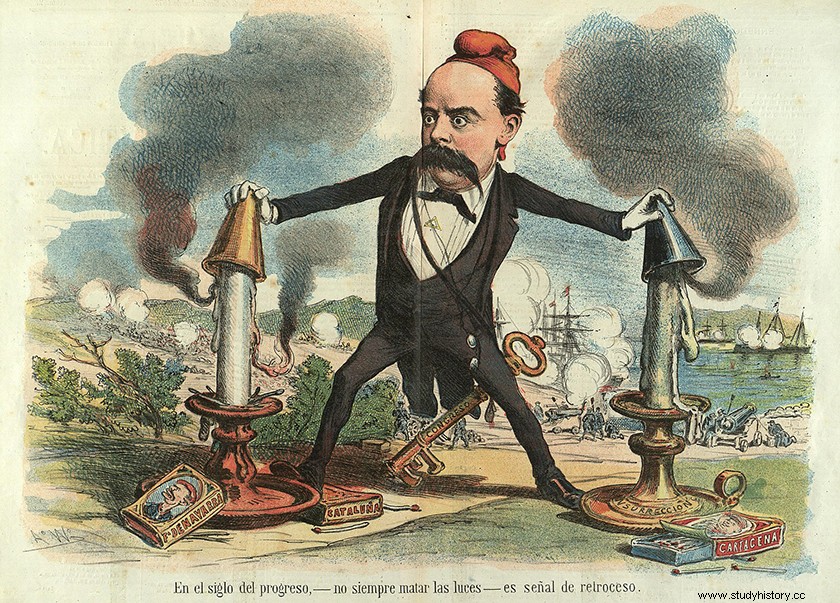

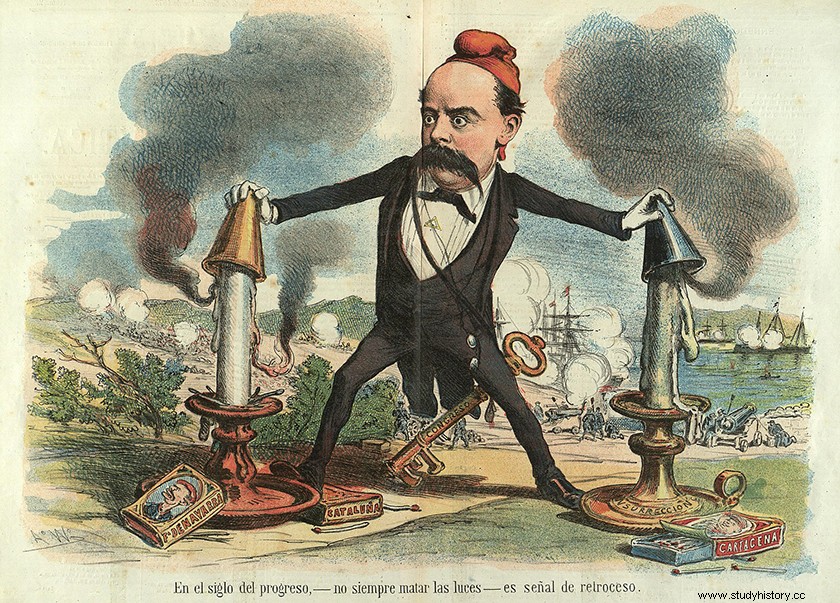

Emilio Castelar putting out the revolutionary fires.

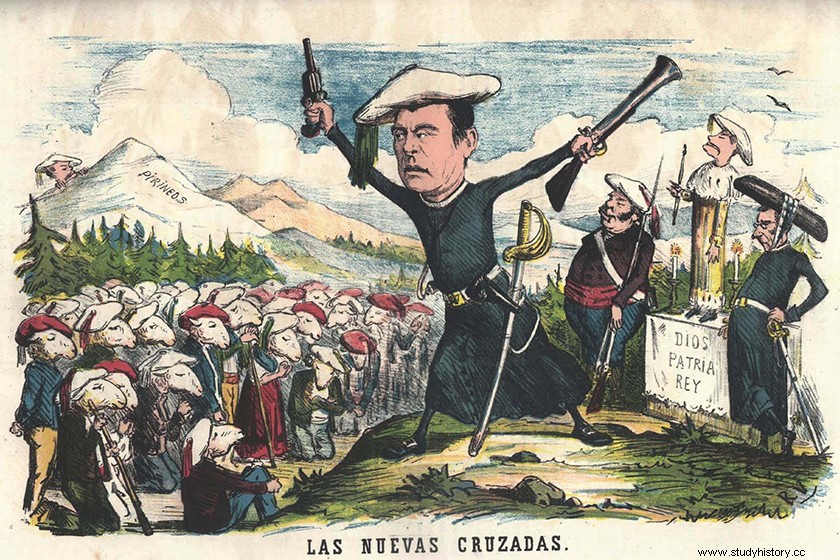

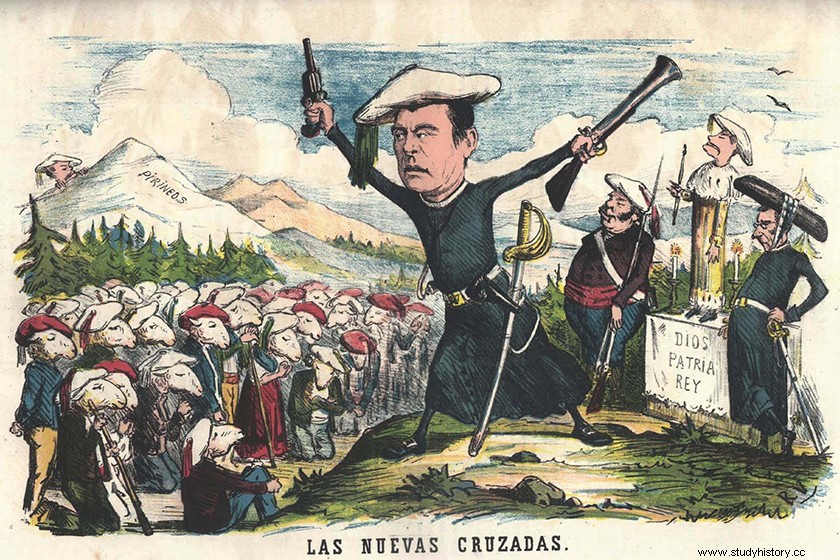

The Carlists.

The first of the great enemies of the Republic was on the battlefield and it was not their own, but rather a matter of inheritance. The Carlist wars undermined the governments of Liberal Spain since the death of Ferdinand VII in 1833. At that time, the Crown of Spain was in the hands of a 3-year-old girl and her mother María Cristina, a supporter of a Constitutional Monarchy, acted as Regent. . Opposite were the supporters of Carlos Luis de Borbón, brother of Fernando and supported by the most absolutist and Catholic sectors of Spain. Since then, the war has been latent in the country, and it awoke every time the Crown or the government approached the most liberal sectors.

This aspect became evident from the arrival of Amadeo I, which was the trigger for what is known by the most current historiography as the Third Carlist War, which began in 1872, is that is, a year before the republican consecration. But obviously the proclamation of the First Republic raised huge blisters within the Carlist, the establishment of the separation between State-Church, lay education, or freedom of worship, were aspects that could not be allowed. The Carlists championed by Carlos de Borbón, grandson of Carlos Luis de Borbón, who named himself Carlos VII and Duke of Madrid, led the country into a profound civil war.

Carlism's greatest strength lay in the Basque Country, in Navarra and in the north of Catalonia, at that time, in addition, new parties from the interior of the Aragonese mountains and Valencian. It is estimated that around 70,000 men were active in the Carlist army, nurtured with weapons from abroad, such as English cannons or French rifles, largely thanks to bribes from the railway facilities of the Basque Country, which had to pay 1,000 pesetas a day to avoid attacks. In addition to the army, the Carlists had other types of forces, in this case the small groups totally outside the law and even criticized by themselves, such as that of the Cura Santa Cruz, capable of entering any town and assassinating any Republican follower .

Carlism, the Christian crusade of the 19th century

The solution to the Carlist War was to give up key aspects of the Republican electoral posters. The abolition of the "fifths", the military recruitment system by lottery that could be circumvented upon payment, was transcendental for them. So the solution was a new army made up of day laborers and unemployed called "the volunteers of the Republic", given their poor military training, members of the permanent armies were placed in front, in this case declared alfonsinos, that is, supporters of the return of Constitutional Monarchy led by Alfonso de Borbón, son of Isabel II. In January 1874 one of them already held the presidency of the republican government, he was an old acquaintance of the previous monarchical governments, General Serrano. His work to lift the siege to which the Carlists subjected Bilbao, a bastion of liberalism in northern Spain, was achieved after 125 days. The very expensive price, putting the Republic in the hands of the military.

The slave owners.

The Carlist war was not the only one that shook Republican Spain in 1873, another latent war was carried out in the Antillean colonies, especially in Cuba. In it we can mean that there were a series of confluences of interests that provided greater political power to the rivals of the Republic.

Every political movement needs financing behind it, the return to the Constitutional Monarchy was endorsed by liberal parties, but with a markedly conservative character. The main one of them was the Liberal Union that during the time of the Republic fell into the hands of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo and its financing came mainly from the so-called slave owners.

The abolition of the slave system in the colonies was another of the highlights of the Republican electoral poster, the highest expression of liberalism could not afford to continue maintaining an economic system that came from the Old Regime. The confrontation with the rich landowners of the colonies led them to finance both the Liberal Union of Cánovas and the Carlist parties. The main character in this case was Julián de Zuloaga, from Vitoria, one of the largest fortunes in Spain in the 19th century, the origin of which was his sugar plantations in Cuba, and the illegal slave trade between Africa and America. Behind this movement is the arrival in the government of the Republic of General Serrano, another of the most outstanding politicians of the Liberal Union, which, by the way, disappeared with the end of the Republic at the time the Conservative Party was born, with the return of Alfonso XII and the constitutional monarchical system. Regarding the Cuban War of Independence, the Spanish Republic was a mere troupe, it was inherited and continued after its disappearance.

The Republicans themselves.

As we have seen in the previous points, both from the battlefield and from political offices, pressure was exerted for the end of the First Spanish Republic. We certainly don't know what would have happened if the Republicans themselves had rowed all at once in one direction. Far from forgetting their political differences to launch the Republic, discussions within the new government were the order of the day. The various events in the street, the result of the enormous impatience shown by both the population and a part of the politicians, when it came to launching the liberal political reforms that the republican ideology carried with it, were the main trigger for the crisis Republic policy.

The convening of the Constituent Assembly, from which the Republican Constitution was to emerge, was a compendium of political visions. On the one hand, the impatient "radicals", and on the other the prudent "conservatives", without forgetting the different vision between the Unitary Republic and the Federal Republic. The discrepancies soon reach the street or vice versa.

Republic yes, but unitary or federal?

The lack of control in the first days became evident, especially in Andalusia, where the hatred of the poor against the rich exploded. One day after the Republic was proclaimed, the oppressed peasants of Montilla, in Córdoba, approached the Mayor's House, destroying and burning all the archives and murdering his employees. Similar riots took place all over the country, a fact that did nothing but redound to the benefit of the monarchists.

In the midst of the debate on the advisability of a Federal or Unitary Republic, on February 22, that is to say 10 days after the departure of Amadeo I, the gathered Catalan councils make the decision to become a federal state. That day all the alarms went off between moderate Republicans and supporters of a Unitary Republic. The then Minister of the Interior, Pi y Maragall, had to come to the fore to annul the agreements pending a true Constitution, which contemplated the political federalism of Spain. But the federal demands not only came from Catalonia, a few days later in Malaga the internationals, as the followers in Spain of the First International that had been born as a labor movement in London in 1864 were known, carried out their own commune, with 10,000 workers armed thanks to the new City Council tax against the propertied classes.

This last fact was not isolated, rather it was the tip of the iceberg of the republican movement that most harmed the newborn Republic, it was called the cantonal movement, to remember the Swiss cantons . It spread rapidly through many cities, mainly in the south of the Peninsula. In Seville they have been strong since June 30, establishing the 8-hour working day, lowering rents by 50%, in addition to confiscating and distributing the lands of the Church. More virulent we can consider the situation in Alcoy, which began as a general strike on July 7 and ended with factories burned and the agents of the civil guard and mayor of the town assassinated.

The movement needed to find a new capital, from which to generate a new Federal Republic, which will bring together the leadership of all the cantons. Cartagena was chosen, its good exit to the Mediterranean, and its fantastic land defenses were the best place to place a new government. Pi y Maragall tried to carry out a text that would recognize the new federal system and calm the revolutionary spirits, it was not possible and he resigned in the month of July. He was replaced by the "moderate" Salmerón, the response of the cities was immediate, in a few days half of Spain appeared quartered, in addition the movement spread to the north in cities such as Ávila or Salamanca.

The defense of the Canton of Cartagena

Cartagena, with the so-called Murciano Canton, was at the forefront of the Federal Republic project, the support of the Navy was essential for the establishment of a provisional directory. The people of Cartagena lent themselves to defend the city under the command of prominent figures such as Antonio Gálvez "antoñete". The petitions of those present in Cartagena did not address only local areas, the best example of capital status was that these petitions brought together the needs of the entire nation, a list of all the feudal privileges that continued to exist in Spain in the 19th century was presented, such as leasehold rents in Galicia or Asturias. On the other hand, policies clearly coming from the International began to be introduced, reminiscent of what happened in Paris. Among them, public salary limit, abolition of privileges for officials, or the creation of state banks, both agricultural and industrial, with a yield limit of no more than 3%. In short, a state where workers feel free to live from their work.

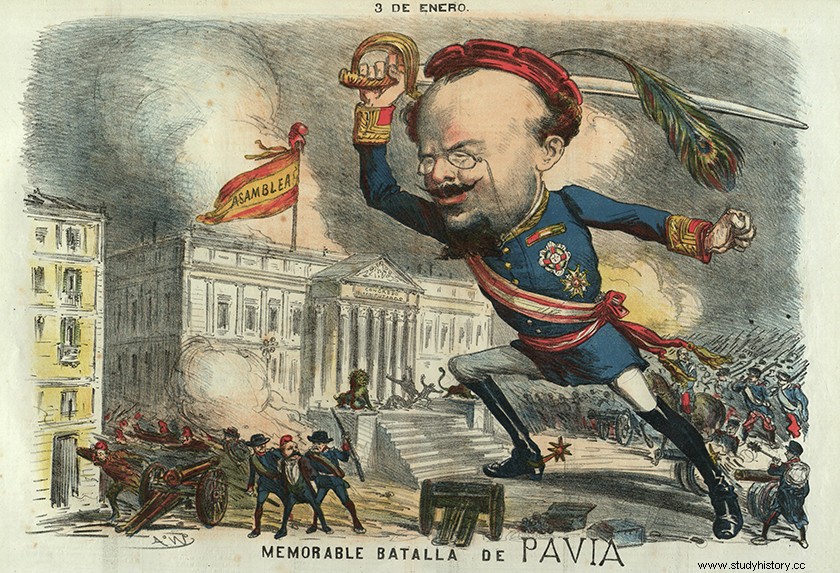

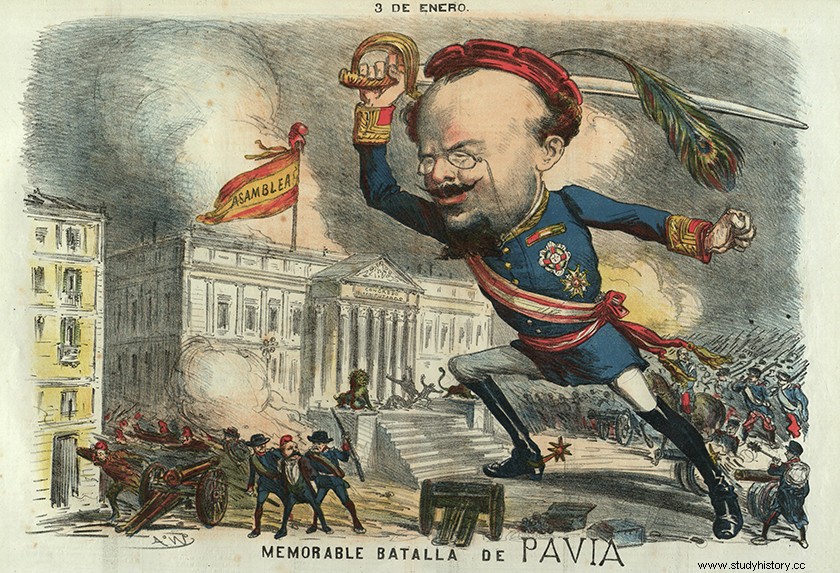

The President of the Republic Salmerón put the monarchist Martínez Campos, and the republican Manuel Pavía, at the head of the army. A month later, Salmerón presented his resignation after refusing to sign the execution of soldiers related to the quartered movement. He was replaced by Emilio Castelar who allowed greater repression against the federalist movement. All this led to the coup d'état by General Pavia on January 3, 1874, who, after seeing that it was impossible for the Republicans to come to an agreement, left a government of concentration, as we have pointed out, under the command of General Manuel Serrano. The political system of the Republic had languished in just over a year, certainly one more, 1874, but under a republican dictatorship that tried to confront the Carlists and independentist Cubans, awaiting the pronouncement of Martínez Campos at Christmas in that same year.

General Pavia at the door of the Spanish courts

The First Republic quickly fell through its own mistakes. It is true that he had powerful rivals and enemies, but impatience seems to have been the greatest of all. 56 years later the republican experience was repeated; impossible to forget how it ended.

More info:

Contemporary History of Spain 1808-1923, Blanca Buldain Jaca (Coor.). Ed. Akal, 2011.