Undoubtedly the knowledge of the alleged first indigenous culture of the Iberian Peninsula, that is, tartessos, continues to be today one of the biggest headaches for historians and archaeologists. It is true that there is no official position on the subject, but today it is taken for granted that we are talking about the first autochthonous political entity of the Iberian Peninsula.

In this article we will try to shed a little light on the current state of research, by the way very scarce, as a summary we will know the main social, economic, cultural and religious aspects especially the first steps of the Tartessian culture. All this from an approach of curiosity and questioning, in the face of clear national policies that turn their backs on the attempt of professionals in the sector to bring to light the truth about Tartessos.

Where Tartessos was developed.

It is evident that the first thing we must know is the geographical space where the Tartessian culture arose. Today there is a general consensus that this culture arose approximately in the 10th century BC, in the triangle formed by the current cities of Huelva, Cádiz and Seville, but more specifically around the lower courses of the Guadiana and Odiel rivers, or at least that reflects the archaeological finds. Note that it will later expand to the rest of what is now Andalusia and Extremadura.

This geographical space around the said X century BC., is assigned to the prehistoric culture of the final Atlantic Bronze. One of its archaeological remains that denote its particularity are the stelae of warriors, which are large stone slabs engraved with figures of a warrior. Due to the decontextualization with which the vast majority were found, at first they were assigned as markers for their tombs. But the lack of bone records, not only around their discovery, but also in the geographical space assigned to the beginning of the supposed Tartessian culture, has led to a consensus that they are territorial markers, whether they were agricultural, mining or simply places. by the way to them.

This fact, together with the lack of burials, may be one of the signs that we are facing a different culture, both from the rest of the Iberian Peninsula, and from that of its future members come from outside, see Phoenicians and Greeks. To solve the problem regarding the way to say goodbye to their dead, experts see in some archaeological remains found in the rivers of the area, a possible answer.

Huelva Estuary reservoir.

In the spring of 1923, while cleaning the bottom of the Ría de Huelva, a dredger extracted 397 metal pieces from the bottom. The vast majority were weapons and among them some of the best examples of carp-tongue swords on the Peninsula stood out. Along with them, spears, daggers, or arrowheads completed the outfit of a supposed Tartessian warrior, but to this we must add ornaments such as brooches and pins.

It was easy to believe that they arrived there due to the sinking of some merchant ship, but subsequent findings questioned this hypothesis, including a Greek helmet or a statuette of the God Melkart. In addition to the various dates that gave dates, you included between 1300 and 750 BC.

With all this, Belén and José Luis Escacena, professors at the University of Seville, proposed a hypothesis in 1995. The ritual for the transfer of their dead by the inhabitants of Tartessos consisted of depositing them through some system in the rivers of the area, next to them the typical trousseau. This fact is not exclusive to the Tartessian culture, but rather a current that comes from the Atlantic cultures, since similar vestiges have been found in different areas and sometimes even together with bone remains.

Estuary of Huelva deposit

Despite this, this lack of exclusivity cannot subtract an iota of importance from the differentiating fact with the majority customs in the Iberian Peninsula, before and during the culture of Tartessos, obviously We talk about burial and cremation. By the way, practices that our protagonists adopted, after the arrival of the Phoenicians and Greeks to the Iberian Peninsula, changing their peculiar way of saying goodbye to their relatives.

Also say that this position finds its detractors, who see it as very difficult for all the materials deposited throughout a wide temporal space to end up at the same destination. These continue betting on the sinking of a supposed ship, or a deposition before the end of a lineage that lost its possessions. Both poses miss details, like the Greek helmet.

The religion of the Tartessians.

A small paragraph to remember religion as the great unknown of this supposed Tartessian culture. The differential fact of saying goodbye to their dead in a natural environment can lead us to interpret religious practices rooted in nature, possibly very similar to Celts or Iberians. It is evident that we are talking about their intrinsic religion, since after contact with the Phoenicians and Greeks they adopted, as in the case of the cities that we will see below, non-native traditions.

From this point on, one of the most important archaeological sites on the Peninsula would come into play, in relation to the world of Tartessos. We are talking about Cancho Roano in the province of Badajoz, according to all indications a religious temple. But in my opinion, it is not very defining to know this Tartessian religion, it is only necessary to remember that this site is dated approximately 550 BC, the date on which the collapse of the Tartessians begins and the transfer to the pre-Roman people of the Turdetans.

The birth of the Tartessian cities?

Two have been the main positions among historiography for the knowledge of the genesis of the Tartessos culture. The first of them called “colonialist ” shows us an oriental substratum at the beginning of it, its defenders certainly less and less, they rely on the arrival of the Phoenicians and Greeks. Since the 10th century BC, and prior to the first settlements of these cultures in the Peninsula, they were introduced among the indigenous people of the late Atlantic Bronze Age, changing their customs and creating this Tartessian culture.

But the one that is defended with the most evidence is the “evolutionary position ”. It is also based on the arrival of the Phoenicians and Greeks, but to interact commercially with the indigenous people and form this supposed Tartessian society. Through these contacts, the local elites will introduce these new customs, adapting them to the idiosyncrasy of the native population. It is in this place that the cities of the Iberian Peninsula appear, let us leave aside whether they are Phoenician, the first Orientals to settle, or they are Tartessian, since it continues to be a matter of daily discussion among experts, but rather explain it to the famous treasure of Carambolo, which one day rises as a Tartessian and the next as a Phoenician.

The settlements of the X century BC, that is to say at the beginning of Tartessos, are the typical settlements of the recent prehistory of the Iberian Peninsula, in this case in the form of circular houses of a single stay and with little durable materials. Undoubtedly, as was usual among the economies dedicated to subsistence agriculture and livestock, governed by some type of superior entity, as the warrior stelae show us. But something changed with the arrival of the first Phoenicians in the 9th century BC. As is known, this occurred, among other things, to obtain minerals with which to pay tribute to the Assyrians. So the mountain range of present-day Huelva became his destiny, gold, silver, copper or tin was his claim.

This produced a rapid change in the settlements, the Phoenicians contributed their rectangular houses, with different rooms and even two levels. All of them around structured streets and the appearance of public buildings, whether economic, political or religious. Both aspects are important to assign them the change of nomenclature from towns to cities. From this first phase are cities such as the current Cádiz or the Doña Blanca settlement, both clearly assigned to the Phoenicians. But also others such as Huelva, which, as we will see later, continue to have serious doubts about assigning them to one, the other, or both.

The Old Roof.

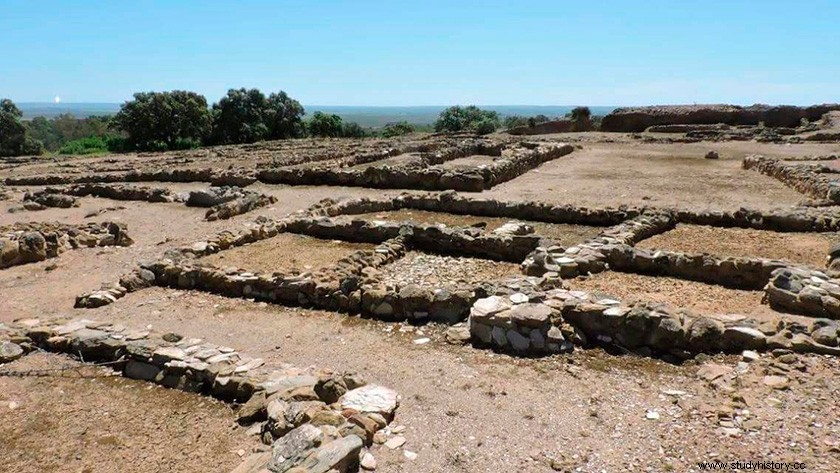

Undoubtedly one of the most significant sites of this transition, also the most clearly assigned to an autochthonous culture, that is, Tartessian, although using the physiognomy of the Phoenician cities of the coast . Its extension of more than 6 hectares reveals a medium-sized city, halfway between the mineral extraction areas and their shipping ports.

We are therefore facing one of the first supposedly Tartessian cities, well organized through blocks and streets, but still in the incipient phase of separation of public and private. It is necessary to emphasize that its construction technique based on a stone plinth that rests on the mountain without any type of foundation, is the usual one in the Mediterranean cultures of that time.

The pottery of the Tartessians.

As it is known in prehistory, from the Neolithic, one of the best markers of the different societies or cultures are the remains of ceramics. Tartessos also finds in this aspect a differentiating fact. Although we are talking about a period in which boquique ceramics flooded a large part of the Iberian Peninsula, in the geographical space assigned to the Tartessian culture two very different ones appear.

On the one hand we find what we can call everyday crockery, it is the burnished grid ceramic, dark in color and rudimentarily made by hand or on a slow lathe, its appearance is quite crude. On the other hand, the so-called Carambolo-style painted ceramic , offers a much better appearance, it must have been the tableware of the higher classes. Its elaboration should not be very different from the previous one, but painted with red tones on an ocher background, its appearance was much more pleasant.

The arrival in history of Tartessos.

Until now we have talked about burials, habitats or material culture, all of which are aspects that help us differentiate the Tartessians from other prehistoric societies of the Iberian Peninsula. But with the arrival of the Greeks in the 7th century BC, we suddenly find that apart from archaeological evidence, we have written evidence to support the existence of this Tartessian culture.

Without a doubt the main one comes from the father of Western history. Herodotus describes for us the contacts of the Phocaean Greeks with King Argantonius, sometime between the 7th and 6th centuries BC. He also describes him to us as a king who exercises tyranny as a form of government. It should be remembered that this adjective is not at all pejorative in the Greek world, which sees tyrants as those who provided Ancient Greece with the economic improvements that led to the arrival of Greek democracy. Therefore it is not surprising that Herodotus described Argantonius to us as a good king, who helped his people and even the Greeks.

On the question of the longevity of this king, 120 years of them 80 in office, it is usually solved with the thought of finding ourselves before a dynasty, all of them with the same name . But also in this list of Tartessian kings, according to Professor Gonzalo Bravo, other names appear, some of them mythical such as Nórax or Gargoris, along with others supposedly real such as King Habis.

The Tartessos in the orientalizing period.

From here, among the few literary sources and archaeology, we have been presented with this first political entity in the form of a state in the Iberian Peninsula. Supposedly with a great capital called Tartessos, which despite the efforts of A. Shulten, among others, we still do not know its whereabouts.

As reflected above, the arrival of the Phoenicians and Greeks transformed this society. Its economy could be one of the most prosperous in the Mediterranean. Its mining, especially in terms of silver, complemented with the technological advances that came with the Phoenicians, made its gold work travel the Mediterranean. The potter's wheel was generalized for mass production of high-quality ceramics, together with the introduction of iron metallurgy.

Gold ring from the Necropolis de la Joya in Huelva

All this hand in hand with livestock and agricultural improvements, especially in the use of the rich land for the production of vines and olive trees, products with a high economic return. This provided the obvious local elites who undertook the aforementioned improvements in the cities, in addition to their fortifications.

Necropolis of La Joya in Huelva.

Well, all this spectacular Tartessos is still waiting for a clear confirmation of its existence. While historians and archaeologists continue to search for evidence, it seems that our authorities have not been, nor are they about to unearth this first political entity of the Iberian Peninsula, or at least that I can deduce, from facts like the one I want to narrate below.

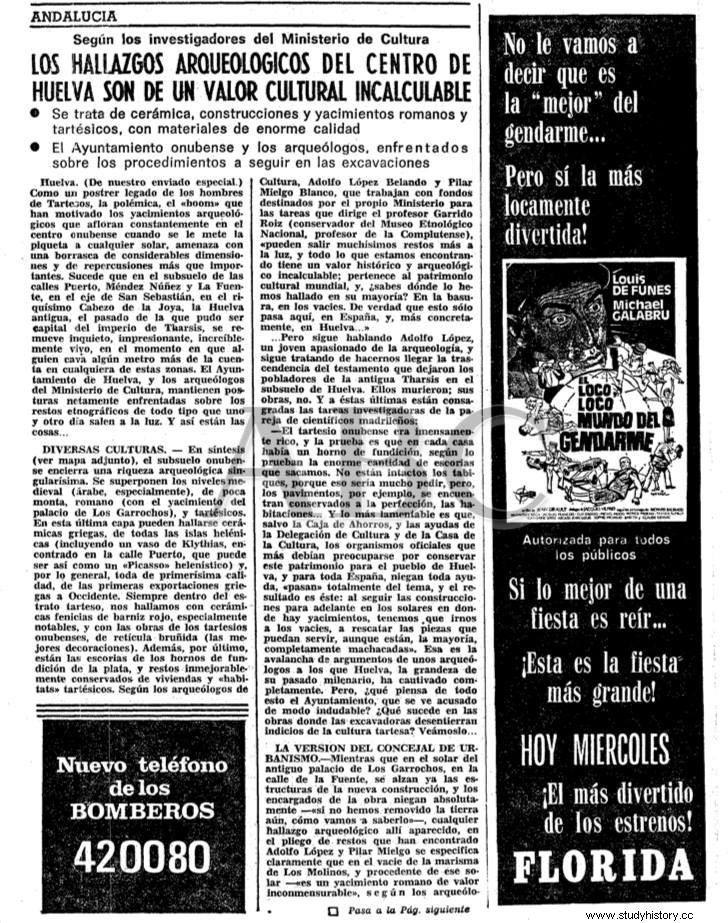

A few months ago in Walking through history we referred to Asta Regia, the site near Jerez de la Frontera as a possible Tartesso (if you want to know it follow this link). A few days later, via social networks, one of the archaeologists in charge of the excavations in the center of Huelva, in the 1980s, contacted us. His answer caught my attention; “let no one look for Tartessos, because it is below Huelva and no one is going to get it out of there”. In addition to ensuring that the royal tombs of the Tartessian kings were in that place. He referred, among others, to the archaeological site of the necropolis of La Joya de Huelva, as an example he sent me these two photographs on a newspaper dated December 29, 1982, without a doubt, as they say, they are priceless.

As obviously we cannot guarantee anything, we must go to the museums, to locate some of the pieces extracted from the place before the site was abandoned, and put earth on it , at least in certain parts. It seems that the municipal authorities feared for their urban plans.

Huelva Museum.

According to the director of this museum in 2015, Mr. Pablo S. Guisande. The necropolis of La Joya de Huelva had at least 19 tombs with abundant evidence that its tenants could have been Tartessian kings. Among other elements, a large number of gold, silver and bronze jewels were found, as well as foreign elements such as ivory or ostrich eggs.

Of all of them, we can highlight a piece found in tomb nº 17 that served as a hubcap for a car, a fact that demonstrates the high status of the individual who was there. We can also highlight two vases with a unique physiognomy in the world, a differential fact that can refer us to a unique culture. One of them shared a tomb with the previous element, it is a vase with an inverted lotus flower with a cone-shaped support. The other was found in the next tomb, No. 18, and is a curious jug with a handle in the shape of a deer and a top in the shape of a horse. I leave you the museum website at the end so that you can know the rest of the elements.

Vases from the La Joya Necropolis in Huelva

Conclusions.

We have begun by saying that we are facing one of the most significant periods in the protohistory of our Iberian Peninsula. Undoubtedly, one day being able to discover the beginnings of our history is an exciting task. The mythical capital of Tartessos could reveal many secrets and also be able to compare it with historical cities of this period, such as Athens or Rome itself taking its first steps.

The detractors of this alleged first Hispanic culture, usually emphasize the similarity with the Phoenicians. And I say, more than 300 years of coexistence are enough to acquire behaviors and learn from other cultures to make your own progress. It is clear from the archaeological record that the Tartessians learned much from the Phoenicians, and the latter have gone down in history as merchants. Therefore, the space of coexistence and not of occupation seems the most logical to find the truth about the world of the Tartessians. We will try to be attentive to the news that continue to emerge on this exciting topic.

I leave you with one of the most entertaining stories you can find about the Tartessian world from the pen of Manuel Pimentel.

More info:

Tarteso and the colonial period, María Pilar San Nicolás, Topic 9 of Recent Prehistory of the Iberian Peninsula, Ed. Uned, 2013.

New History of Ancient Spain, Gonzalo Bravo, Ed, Alianza, 2011

Images:

museumsofandalucia

Links of interest:

museumsofandalucia

institutional

tejadalavieja