They say that on the morning of July 22, 1921 , when the captain general of Melilla, General Manuel Fernández Silvestre , present in the Annual camp, had decided to withdraw from the besieged position in what would later become a cruel massacre, his personal friend, the influential Sharif of the Kabyle of Beni Said, Kadur Namar, who was at his side , told him:"Don't retreat, general, don't retreat, look how abandoned a Kabyle is a rebelled Kabyle." That same afternoon, with the bloody flight of the Spanish army from Melilla underway, the sherif appeared in Quebdani to ask Colonel Araujo to withdraw immediately. Three days later, the 900 soldiers in the position were massacred after voting to surrender and hand over their weapons. It was not the first notice that Silvestre received.

In a confidential report dated February 1921, Colonel Gabriel Morales Mendigutia, chief of the Indigenous Police , had warned him against taking too much haste to cross the Nekor River in the direction of Alhucemas and had been more in favor of consolidating the rearguard and advancing cautiously along the coast than continuing with the dizzying land occupation strategy that had made him famous. to Silvestre during the first half of 1921 and that had led the Melilla army to stretch the elasticity of its troops to the maximum. Lieutenant Colonel Ricardo Fernández Tamarit, head of the 3rd Battalion of the 68th Africa Infantry Regiment, stationed in Bu Becker's Zoco el Telatza, had also warned his boss and personal friend, in a private letter dated May of 1921, that the Kabyles in the rear were not subdued, that the new positions taken were difficult to defend, that the Rif people were warriors by nature and knew that the further the army advanced, the worse their defensive situation would be and he even reminded him of the precedent by El Rogui .

The rise of El Rogui

When Sultan Hassan I died in 1894, he was succeeded to the Moroccan throne by the youngest of his nineteen sons, his favorite, Abd El Aziz , to the detriment of the others, including the eldest son, Prince Muley Mohamed, known as "the One-Eye", who was imprisoned in the imperial city of Meknes by the grand vizier Ahmed Ben Musa, chamberlain of the deceased sultan, to ensure the succession , since the chosen one was only fourteen years old. Another of the victims of the purge was the brother of the old sultan and uncle of the new one, Muley Omar Ben Mohamed, Khalifa of Fez, who also ended up in prison along with his closest collaborators. Upon the death of the grand vizier, the new sultan, Abd El Aziz, an eccentric collector of luxury cars, watches and exotic animals, began to surround himself with foreign advisers and even tried to introduce a new tax to pay for his considerable expenses. , the tertib , which taxed property, including livestock, even contravening the dictates of the Koran. Naturally, he became very unpopular among his subjects, who preferred to support his other brothers or any member of a chorfa family, that is, a descendant of the Prophet, who demonstrated with his baraka that he enjoyed divine protection. .

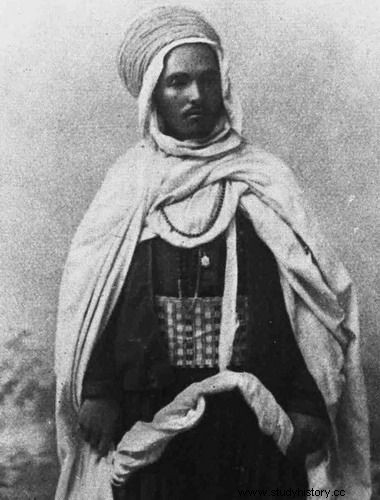

In 1902, when the former secretary of the Khalifa of Fez, a character named Yilali Ben Salem Zerhouni el Iusfi, was released from prison, he decided to play his trick by posing as Prince Muley Mohamed to postulate itself as the true holder of the rights to the sultanate. This impostor, well versed in the interiorities of the Mazjen, that is, the structure of the Moroccan state, also skilfully imitated the prince's gestures, pretending to be one-eyed and even using magic tricks to dazzle his audience and thus managed to convince a growing following of followers that he had more right to the sultanate than his "brother" Abd el Aziz. He was known as Bu Hamara, "the one with the Donkey", for presenting himself in this guise in the souks claiming his candidacy, which is why he was also known as El Rogui, "the Pretender" . In fact, his family origins were very humble, based in the customs of Mount Zerhoun, near Mequinez, in the Kabyle of Ulad Yusef, but, due to his unusual intelligence and his great capacity for assimilation, he was able to brilliantly complete his studies. Koranic and even pass a military engineering course taught by the French administration, where he also developed contacts with French intelligence through the French topographer Gabriel Delbrel, who would later perform important services for the Spanish Protectorate. Once he had accommodated himself to his new personality as the son of the previous sultan and heir to the throne, through pacts and marriages of convenience he obtained the support of some Kabyles and conquered Taza in October 1902, where he defeated the mehalas that the new king sent from Fez. Sultan to try to subdue him, which increased his prestige and the support of the Kabyles. In April 1904 his forces managed to dislodge from Farjana the representative of the Mazjen, Pasha Bachir Ben Sennah.

At first, El Rogui benefited from French support, which sought to undermine the sultanate to facilitate French penetration in Morocco , but the Entente Cordial of 1904 between France and Great Britain facilitated relations with the Moroccan royal family, with which the pretender lost French support and was forced to seek Spanish protection. El Rogui appointed his friend Delbrel as Chief of Staff with the name of Mouslim Mouttakillah and finally settled in the citadel of Zeluán, where he received the submission of the Kabyles located to the south of Melilla. Although Spain, forced by the Algeciras conference, did not recognize his authority, it maintained a good relationship with the pretender, especially since the latter controlled the region's iron and silver-lead mines and administered the concessions with Spanish companies. and French. To this end, the construction of the necessary infrastructure began, including warehouses, offices, accommodation for the miners and even a railway line to transport the mineral to the port of Melilla. The successful development of the exploitation and the safety of the workers required not only the umbrella that conferred military protection, but also the support of a local authority that controlled the Cabileños.

The withdrawal of El Rogui:the background of Annual

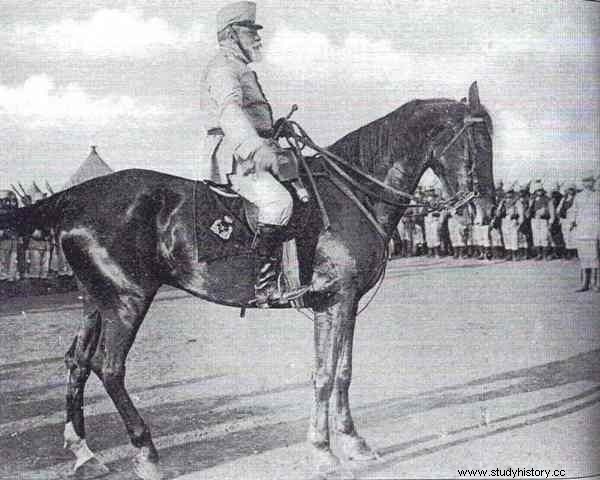

El Rogui ruled the region with an iron fist, negotiating the mining concessions in exchange for juicy payments that they would allow him to maintain his authority, which he also imposed through cruel punishments and large taxes. The understanding with the Spanish and French, with economic and political interests in the area, kept El Rogui in power and he reciprocated by facilitating mining exploitation and the construction of railway lines, until, in 1908, some Kabyles refused to comply. your demands. Then, in September, El Rogui sent a mehala with two thousand ascarids to Beni Urriaguel under the command of his faithful shaykh Yilali Mul Al Udu, former Ascari of the sultan's black guard, who raided the customs of the Kabyles of Tensaman and Beni Tuzin and appeared on the banks of the Nekor river, near the bay of Alhucemas, threatening to occupy Axdir, the heart of the Kabyle of Beni Urriaguel. At that moment, General José Marina Vega intervened. , military governor of Melilla, in aid of the population of Axdir, who traded with the Spaniards on the Rock of Alhucemas, and warned El Rogui that an attack on the town would be considered an attack on Spain. The Rif leader did not have it all with him either regarding his superiority against the reinforced hark that stood up to him or in terms of the loyalty of the faithful Kabyles of his rearguard, who could fall on him at the first setback, for which he ordered the withdrawal of his troops. This movement was interpreted by the Rif people as an unequivocal sign of weakness, which caused the hark to attack the retreating mehala, in which not only casualties occurred, but also desertions to join the enemy.

In the dramatic flight from him, El Rogui's troops were massacred by the Kabyles through which they crossed, which rose in their path, with the aim of profiting by plundering the vanquished. El Rogui, with what was left of his mehala, had to hastily take refuge in his citadel in Zeluán on October 7, 1908. The following day, a serious incident took place in one of the mining operations:due to threats from some Rif workers , the head of the mine decided to flee to Melilla, which caused the rest of the frightened miners to seek protection in Zeluán, from where El Rogui's troops escorted them to the Plaza, and then proceeded to cruelly punish the miners. Cabileños who had caused the riots. The chiefs of the Kabyles of the area, initially loyal to the suitor, who also wanted to seize the benefits of managing the mining concessions, were aware of the collapse of their mehala and, aware of their weakness, took advantage of the discontent of the population before the submission of El Rogui to foreigners, his cruelty and greed, and, commanded by Mohammed Mizzian, holy man of Segangan, they used this incident to promote a generalized rebellion, so that the pretender had to take refuge again in his citadel, which was besieged until reaching a critical situation of lack of supplies, as happened thirteen years later in the nearby fortress of Monte Arruit with the last surviving Spanish troops of the Annual disaster.

Only a risky maneuver saved the situation. El Rogui ordered a convoy protected by his infantry troops to leave through the main gate of the citadel. The hark that surrounded the position, fearful of the counterattack of the cavalry that remained inside, preferred not to harass him. Attention diverted, El Rogui ordered to blow up the opposite wing of the fortification with explosives and escaped through there with his cavalry, while the Harqueños stayed looting the abandoned citadel. El Rogui's troops had to continue fleeing towards Taza, until, in the Uxda area, they were definitively defeated and their leader, captured in August 1909 by the forces of the new sultan Muley Abd El Hafid, true brother of the previous sultan Abd el Aziz, whom he had already overthrown in January 1908. El Rogui was taken to Fez inside a small cage transported by a camel and there paraded through its streets to the delight of the crowd. The few survivors of his army paraded in chains two by two with an arm or a foot amputated to later be decapitated, because without their heads they could not enter paradise after death. Following an ancient custom, the heads were treated in brine to be able to expose them publicly for days, despite the repeated protests of the Western foreign consuls stationed in Fez due to the barbaric practices and cruel torture inflicted on the vanquished. There are different versions about the end of El Rogui; one of the most popular tells that the sultan had reserved a special treatment for the enemy:the cage of the lions that he had inherited from the private zoo of his brother who had deposed him. The man must have arrived so battered that even the felines discarded such a delicacy, but such a miraculous prodigy in no way softened Abd El Hafid, who ordered his black guard to shoot him and then burn his corpse to prevent his access to the Muslim paradise.

The prophecy of El Rogui

El Rogui had previously sent a letter to the Melilla authorities where he prophesied the costs and suffering that his absence would cause Spain in the form of money, tears and rivers of blood . El Rogui was a cruel leader with his people and served the occupying forces in exchange for large payments , but while he dominated the area, peace reigned and the agreements were respected. Those who followed him were no less ambitious in their economic demands on him and his protection guarantees were not such. In addition, they considered the previously negotiated concessions as illegitimate, they tried to obtain more money for them and they also demanded payment for the land through which the railway ran. Precisely, a series of incidents with railway workers began what would become known as the Melilla campaign of 1909, which would lead to sad events such as the Barranco del Lobo Disaster and the Tragic Week in Barcelona> , when replacement troops were shipped there for the war in Morocco.

But the greatest disaster would occur in the withdrawal of Annual, Thirteen years later, the disastrous and merciless harassment that El Rogui's troops suffered in their flight would be repeated almost in the same scenarios with the Army of Melilla in disarray, leaving a bloody trail of some ten thousand corpses on the way. Here Aldous Huxley's famous phrase makes sense:"Perhaps the greatest lesson of history is that no one has learned the lessons of history."

Bibliography

- Albert Salueña, J. (2015), «Yilali Ben Salem Zerhuni el Iusfi. Known as Muley Mohammed Ben Muley the Hassan Ben Es-Sultan Sidi-Mohammed Bu-Hamara. The Rogui". In Guerrero Acosta, J. M. (dir.), The Spanish Protectorate in Morocco. Biographical and emotional repertoire . Iberdrola, Bilbao.

- Albi de la Cuenta, J. (2016), About Annual . Ministry of Defense, Madrid.

- Caballero Echevarría, F. (2013), Spanish interventionism in Morocco (1898-1928):analysis of factors that converge in a military disaster, Annual . Editions of the Complutense University, Madrid.

- Fontenla Ballesta, S. (2017), The Moroccan War . The Sphere of Books, Madrid.

- González Alcantud, J. (2014), «Cruelty as a symbolization of oriental despotism. The case of the execution of Rogui Bu Hamara in Fez in 1909”, in Lisón Tolosana, C. (coord.), Anthropology:symbolic horizons , Tirant Lo Blanch, Valencia.

- Francisco, L. M. (2014), Dying in Africa , Review, Barcelona.