In the 1st century AD. C. a new hero appeared in literature. So Silio Italico wrote Punica , an epic poem about the Second Punic War (218-201 BC) who faced Carthaginians and Romans. At a certain point in the story, an extraordinary warrior emerges:

The action is set in the Roman assault on Hanno's camp in 207 BC. C., and Laro is a mercenary who fights in the Carthaginian ranks . Silius continues:

Next, he describes his tremendous fight with Lucius Cornelius Scipio , who, finally, with great difficulty, manages to bring him down. This is the only ancient mention of this exceptional character.

The writer and the barbarians

Did Laro exist? Probably not. Punica , although historically well documented, is pure literature , a great epic in the style of the Iliad or the Aeneid in which powerful warriors fight to decide the fate of the world. When building his universe, Silius used exotic, historical and mythological names to create his secondary characters, mixing elements from different eras with which to adorn his work. In all likelihood, Laro is just that, an attractive literary device .

In fact, there weren't even any Cantabrians in the Second Punic War; neither the Romans nor the Carthaginians had had enough contact with those peoples yet. What happens is that, when Silius wrote his work two hundred years later, the Astur-Cantabrian War (29-19 BC) was recent. , which culminated the Roman domain of northern Hispania. In addition, this conflict was accompanied by a powerful propaganda apparatus:it was sold as the great military achievement of Augustus, presenting the Cantabrian peoples as the barbarians par excellence. That is why Silius introduced northern characters in his story and reproduced various topics about his savagery and ferocity, because that theme was easily recognizable for the public of his time, although it had nothing to do with the historical time he was living in. talking. Laro is a myth conceived by the imagination of a poet in a certain political context.

Laro, the Cantabrian hero

Later, for centuries, Laro remained practically forgotten, while other Hispanics, such as Viriato or the numantines , were becoming authentic national heroes . It went unnoticed even in the 19th century, when the indomitable Cantabrian towns began to be seen as a perfect romantic example of independence from foreigners. After all, Laro's story was not the most appropriate, since his only merit was fighting as a mercenary for the Carthaginian invaders, one of the most reviled civilizations in Spanish tradition, which followed the Greco-Roman trail in this.

Suddenly, however, Laro was reborn. The Cantabrians , by Joaquín González Echegaray (1966), can be considered a pioneering work of the academic historiography on the Antiquity of that region. In it, this character has an important role, for example, to speculate on the appearance that his people must have had:“it seems, then, that the Cantabrian was usually tall and stocky, which allows us to assimilate him to a more Nordic racial type. than the Mediterranean type, short and nervous” (p. 123). Although he admitted his literary nature, the temptation to imagine his beloved Cantabrians as colossal northern warriors, using Laro as the prototype of an entire ethnic group, was stronger.

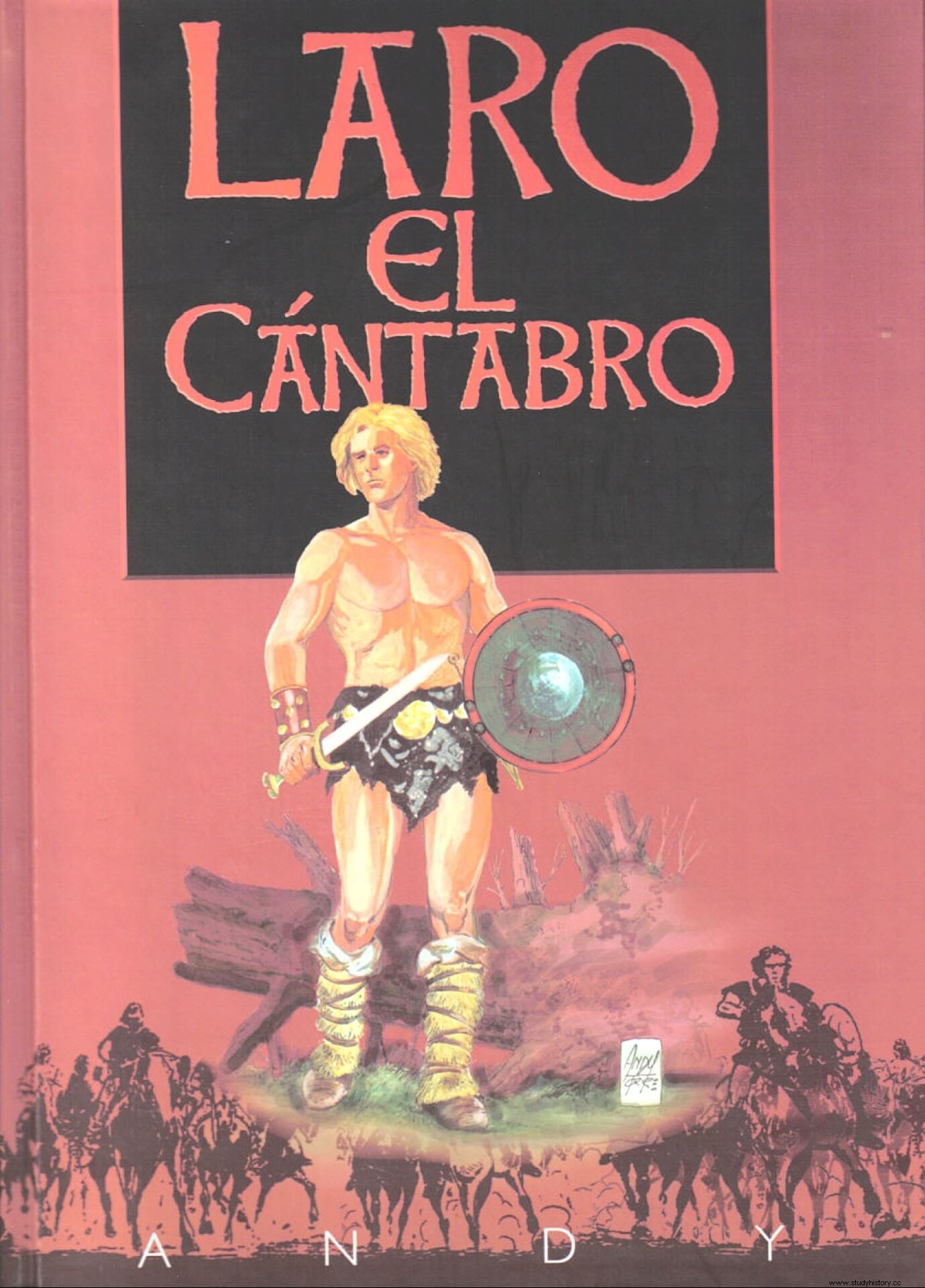

Echegaray's book is just an early sample. The truth is that, in the following decades, Laro came to the foreat the regional level. Certain scientific and informative works have maintained this tendency to idealization, while comics and historical novels have turned him into a popular icon, omitting his role as a mercenary and transforming him into a leader of the anti-Roman resistance. Even the very name of Laro spread among Cantabrian babies. How can a forgotten literary character become a hero of this caliber?

A propitious moment

Dates are key. The figure of Laro began to become popular between the 60s and 80s, the time of the Democratic Transition . He wasn't the only one, he did too Corocotta , the other Cantabrian hero, in this case "invented" by Adolf Schulten. Actually, that period was fundamental in the investigation of the remote past of the region, its recreation in literature and cinema, and the commemoration of it in public monuments. Many of the scientific and creative results of that phenomenon have been very valuable, but just as interesting are the political implications of it.

Evidently, the rediscovery of Laro has a lot to do with the formation of theautonomous community of Cantabria . In the process of building the autonomous regime of 1978, the areas that had little previous nationalist or regionalist tradition, as is the case of Cantabria, had a special difficulty in justifying the claim of their powers against Franco's centralism and in competition with the rest of the communities. In this process of legitimation, it was essential to rescue any historical resource that supported their identity discourse, however weak it might be at times. Apparently, the new political project for the future required rebuilding a past that was up to the task.

Undoubtedly, the resistance that the Cantabrians offered to the Roman conquest was a good deed to celebrate in that sense, but in that story a well-known hero was missing, an exemplary individual who could serve as a reference. Searching among the sources, Silius's poem provided the singular leader that was needed. In an ideological environment that feeds this type of myth, Laro has come to be assumed in the collective imagination as an ancestral symbol of Cantabrian culture. The hero, conveniently reinvented , was ready to fulfill his new assignment.

Bibliography

- Aja Sánchez, J. R. et al . (eds.) (2008), The Cantabrians in antiquity:history versus myth . Santander:University of Cantabria.

- González Morales, M. R. (1992):«Racines:la justification archéologique des origines régionales dans l'Espagne des Communautés autonomes», in Shay, T. and Clottes, J. ( eds.), The limitations of archaeological knowledge . Liège:Marcel Otte-Université de Liège, pp. 15-28.

- Núñez Seixas, X. M. (2005), «Inventing the region, inventing the nation:about autonomous neo-regionalisms in Spain in the last third of the 20th century», in Forcadell Álvarez, C. and Sabio Alcutén, A. (eds.), The scales of the past . Huesca-Barbastro Institute of High Aragonese Studies-UNED, pp. 45-80.