Although in the Modern Age weapons traditional swords lost importance on the battlefield, the sword became a symbol of prestige and nobility , since its possession was associated with the upper classes. This behavior was emulated by the lower classes, who wanted to appear higher in status. In this way, it became common to carry a sword as if it were one more element of clothing [1]. Its use as a means of personal defense or honor was also widespread. In this context, two weapons stand out for the frequency of their use and the number of treatises dedicated to them. We refer to the hand and a half sword and the rapier sword.

The hand-and-a-half sword , also called bastard sword or long sword, owes its name to one of its main characteristics:its size, ranging between 100 and 130 centimeters, made it advisable to use both hands to handle it, although, if the situation favored it, could only be used with one. This weapon emerged in the 14th century as a response to plate armor, as its long reach allowed weak points to be easily penetrated; but firearms performed this function much more effectively, so their use ended up being restricted to the civilian sphere, being especially popular in the Italian territories and the Holy Roman Empire. However, from the second half of the 16th century its use plummeted, being replaced by the rapier sword [2].

There is no clear consensus regarding the origin of the term ropera . Some authors consider that it is of Hispanic origin, while others maintain that it derives from the French rapiere . In principle, the word ropera , which we can find in texts from the fifteenth century, designated any sword whose purpose was to be carried with civilian clothing . Later, this term ended up being associated with the model of sword that became widespread in the 16th and 17th centuries [3]:a sword with a long, thin blade designed mainly to thrust , albeit with the ability to cut, with a hand guard on the guard. It was frequently used accompanied by a candle dagger mainly defensive function in the left hand. In the mid-17th century, the rapier was replaced by the rapier, a weapon that was lighter but could not cut [4].

On the other hand, the personal guards of nobles or bourgeois used to opt for the halberd , a weapon that was found to be more useful in the civilian arena than on the battlefield. This is because its long range and its ability to engage the enemy weapon were very useful in protection tasks. For this purpose, the use of the montante was also frequent. [5], a two-handed sword slightly larger than the one-and-a-half sword.

Other weapons that could be found were the cutlass, the sword with a built-in gun barrel, or the “secret sword” , consisting of a weapon hidden inside another object such as a cane, used mainly as a means of self-defense by people who were not used to being armed such as clerics and doctors [6].

Duels in modern Europe

In modern society honor was imposed as one of the most important values , and with it, the need to defend it in any way against the slightest offense. The most used route was that of mourning . Refusing a challenge was considered a clear sign of lack of manliness [7], which is why men, especially those from the upper classes, were frequently involved in situations in which they had to confront someone to defend their public image or that of others. his family, since it was considered that the man was the repository of the honor of his wife and children [8].

The number of duels that were held throughout Europe became very worrying, so the European monarchs had to take action on the matter [9]. The Catholic Church banned duels after the Council of Trent considering them unfortunate events caused by drinking and other excesses [10]. The same was done by other monarchies such as the English and the Hispanic. However, all these bans were to no avail, as many duels continued to take place clandestinely [11]. The Hispanic Monarchy decided to go even further and promoted the creation of a series of laws aimed at reducing the lethality of weapons . Maximum measures were established for swords, certain types of points that were especially lethal were prohibited, and it was established that it was compulsory to always carry a sheathed sword. To avoid picaresque, swords that integrated mechanisms to lengthen the blade and sheaths that allowed the sword to be drawn faster than normal were also prohibited, since this gave the attacker an advantage [12].

Masters and fencing treatises

During the Modern Age fencing halls emerged in which the teachers taught their knowledge to their students. Later, this was done publicly and thus the custom developed of organizing fencing games in some public squares, especially during fairs, in which anyone could participate [13]. For the practice to be safe, “black swords” were used, lighter weight weapons without edge or point and with a button on the tip to offer additional protection [14].

In this context, the figure of fencing masters is of vital importance. . They were men who mastered the handling of all kinds of weapons and who, in addition to teaching their disciples, controlled the development of fencing games. To do this, they used a stud that they placed between the two combatants when they considered that the game should stop. They also had the custom of “flowering” these weapons before the public to demonstrate their skills [15].

The Catholic Monarchs created in 1478 the position of “Maestro Mayor” , whose function was to judge who possessed the necessary knowledge to be officially recognized as a fencing master and teach classes [16]. In the Catholic Monarchy it was forbidden to teach fencing to disadvantaged groups such as Jews and slaves. Doing so could result in the loss of the license to teach, and if someone taught fencing without a license, they faced a very severe fine[17].

At the end of the Middle Ages some fencing masters began to put their knowledge in writing, in the form of treatises describing the most important techniques. These were not intended for a general audience, but for his students. These manuals assumed some knowledge of swordsmanship on the part of the reader, thus omitting basic explanations such as how the swordsman should move. His purpose was not to teach, but to help his disciples remember the lessons taught [18].

The oldest preserved fencing treatise is anonymous and is in the Royal Armories museum from United Kingdom. It receives the name of MS I.33 , dates from the early 14th century and describes some sword and buckler techniques in Latin with some annotations in German [19].

The appearance of the printing press would later encourage the dissemination of these texts, which spread to a wider audience. Throughout Europe several "schools" of fencing arose , that is, several traditions were created that followed common methods, each with a series of significant authors. The most outstanding were the German, the Italian and the Spanish . However, there were also important masters in other countries who left us invaluable texts, such as the Englishman George Silver, author of Paradoxes of Defence (1599) [20] or André des Bordes and his Discours de la théorie de la pratique et de l’excellence des armes (1610) [21].

Fencing schools in modern Europe

The German school:

The German tradition is inaugurated with Johannes Liechtenauer . We know practically nothing about his life, beyond the fact that he lived in the fourteenth century. However, his influence on German fencing was enormous, to the point that Meyer, writing at the end of the 16th century, continues his tradition[22].

Liechtenauer did not write any treaties. The only thing that has come down to us from him are a series of verses that are very difficult to interpret. This difficulty is intentional:his goal was that only his disciples could understand his meaning. These verses were not an in-depth explanation of swordsmanship, but rather a series of easy-to-memorize rhymes intended to help his students remember the lessons [23]. Fortunately, his disciples and their followers translated these verses into a language understandable to the uninitiated.

The most important early modern Liechtenauer successors were Peter von Danzig and Hans Talhoffer . Already in the sixteenth century, mainly two authors stand out. Paulus Hector Mair worked as an accounting officer in the city of Augsburg. A great fan of fencing, he collected a large number of books. Seeing that the art of the sword was being lost, in 1552 he decided to write three treatises in German and Latin for which he invested an outrageous amount of public money, a fact that caused him to be hanged in 1579 for embezzlement [24] . On the other hand, Joachim Meyer published in 1570 Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens , the first fencing treatise printed in German. The main novelty of this book was that, for the first time in the German tradition, it introduced the use of the rapier sword [25].

Italian schools:

The oldest surviving Italian fencing book is the Fiore dei Liberi, from the early 15th century. It is not the first Italian treatise to be written, as Fiore himself mentions other books in his prologue. The next important author is Filippo Vadi, author of De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi , written between 1482 and 1487. This treatise is highly influenced by Fiore dei Liberi, and stands out for being the first to point out the importance of geometry in fencing [26].

Unlike in the Holy Roman Empire, on the Italian peninsula there was not a single tradition based on a single teacher, but many different schools developed. In the 16th century, the bolognese , with Antonio Manciolino and Achille Marozzo, and the Florentine with Francesco di Sandro Altoni [27].

The publication in 1553 of Trattato di Scientia d’Arme, with vn Dialogo di Filosofia , by Camillo Agrippa , marked a turning point in Italian fencing, as it was the first fencing treatise addressed not to the master's students, but to anyone interested in learning. Agrippa did not limit himself to describing techniques that readers should memorize, but he did an argumentative work in which he defended the importance of reason when deciding the actions to execute in a duel [28]. This would have a capital importance in the subsequent development of Spanish fencing.

Agrippa's work was a real revolution for Italian fencing, exerting a great influence on all subsequent treatises . Furthermore, his method became very popular throughout Europe, especially among the nobility and upper classes[29]. In the 17th century, the works of Salvator Fabris, Ridolfo Capoferro and Nicoletto Giganti stood out, imitating Agrippa in his structure, vocabulary and basic principles [30].

The True Skill:

In the Iberian Peninsula in the 16th century, fencing was it had become a game played by the middle classes. Among the masters of this period stands out Francisco Román , whose treatise of the year 1532 has been lost [31]. A school was developed, later called Vulgar Fencing, of a violent nature and lacking in theoretical foundations in which black swords were not treated as replicas of white weapons, so their implementation in a real situation was useless and dangerous. [32].

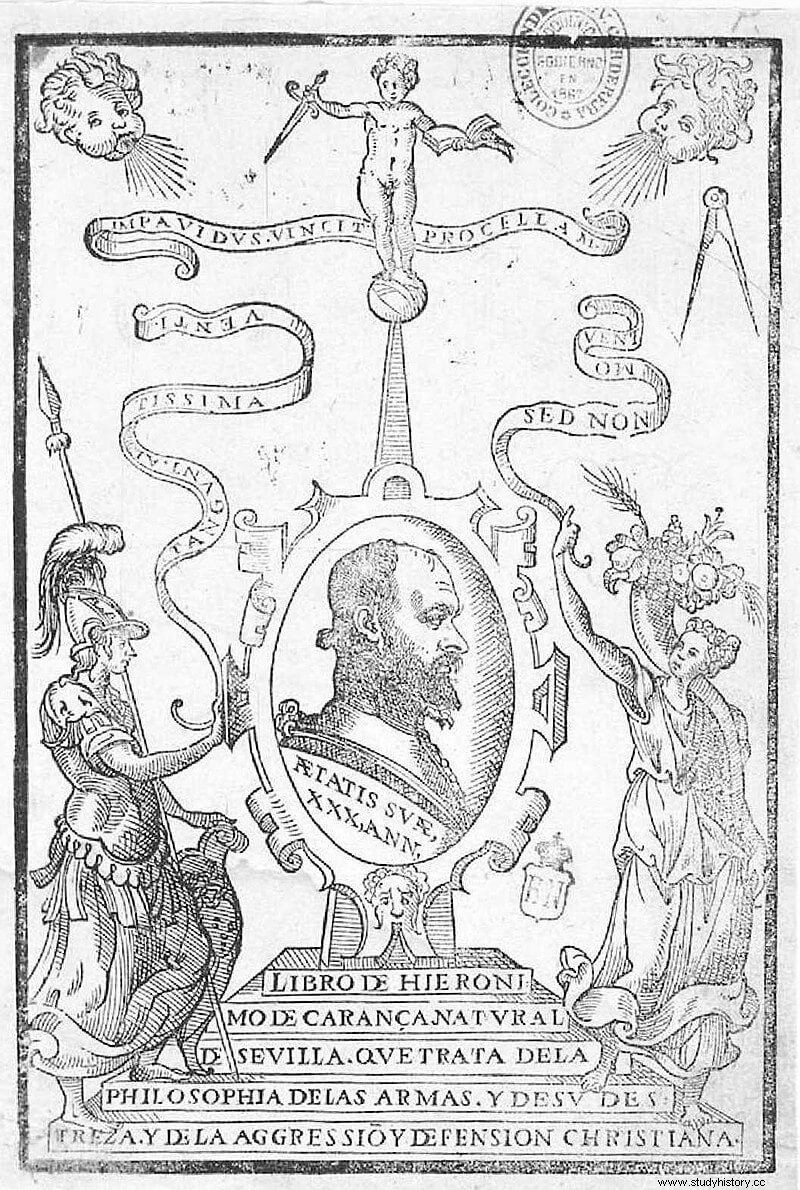

The Sevillian humanist Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza I was not at all satisfied with this situation. Carranza had been a soldier and he had been in the service of the Duke of Medina Sidonia and Felipe II. He also served as Governor of Honduras [33]. In 1582 he published Of the Philosophy of Arms and of their Dexterity and of Christian Aggression and Defense , a book in which, clearly influenced by Agrippa, he defends a theoretical and rational study of fencing using elements of sciences such as mathematics and geometry. His intention was to elevate fencing to the status of a liberal art or science. During the author's lifetime, this book was a great success among the upper class of the time [34].

Carranza had laid the foundations to study the correct handling of the sword but had not created his own method, as his work was more focused on philosophy than on practice. The baezano Luis Pacheco de Narváez was in charge of this . Pacheco, also with a military career , was assigned to the Canary Islands. In 1600 he returned to the Peninsula, specifically to Madrid, bringing with him his Book of the Greatness of the Sword , in which he theoretically and practically developed the principles of the True Skill of Arms, the school of thought founded by Carranza [35].

In Madrid, Pacheco and his theory became very popular. To demonstrate the veracity of his statements, he came to the fore to defend them sword in hand, earning the admiration of characters such as Lope de Vega and Cervantes . He was never defeated; the anecdote that he was easily defeated by Quevedo is a later invention of a biographer of the poet [36]. In 1624 he was appointed Master Master of Philip IV , position that he took advantage of to impose the True Skill of Arms as the only legal fencing teaching method. Several supporters of Vulgar Fencing initiated litigation against him, but the baezano emerged victorious from all of them [37].

Pacheco wrote a total of eleven works. In 1632 he was removed from office and died living in misery in 1640. In the second quarter of the 17th century, various followers of Carranza began to question Pacheco's method. Thus arose a dialectical confrontation that in some cases led to duels between "carrancistas" and "pachequistas". At the end of the 17th century, the Maestro Mayor prohibited teaching fencing to Carrancistas, thus definitively imposing Pacheco's method throughout the Hispanic Monarchy [38]. The True Dexterity of Arms was the most popular school of fencing among the European aristocracy until the French school was popularized at the time of Louis XIV [39].

Bibliography

- AYLWARD, J. D. (1956), The English Master at Arms from the Twelfth to the Twentieth Century , Routledge &Paul, London.

- BOMPREZZI, A. (2012), “The True Skill of Arms or the Path of the Sword of the Spanish Hidalgo”, Desperta Ferro:Modern History, 1, pp. 38-41.

- BOMPREZZI, A. (2013a), «Quevedo never beat Pacheco de Narváez», https://www.academia.edu/42797500/QUEVEDO_NUNCA_VENCI%C3%93_A_PACHECO_DE_NARV%C3 %81EZ , (retrieved January 16, 2021).

- BOMPREZZI, A. (2013b), “Military thinking as a generator of an individual combat system:the True Skill of Weapons”, Perspectives and news from the Military history:a global approach , 2, pp:773-784.

- CIRLOT, V. (1980), “A Classification Model of the Sword. A Purpose of "The Rapier and Small-Sword (1460-1820)", by A. V. B. Norman", Gladius:studies on ancient weapons, armament, military art and cultural life in East and West , 15, p. 5–18.

- DAWSON, T. JAQUET, D., VERELST, K. (2016), Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe (14th-17th Centuries) , Brill, Boston.

- DUEÑAS BERAIZ, G. (2004), “Introduction to the typological study of Spanish swords:XVI-XVII centuries”, Gladius:studies on ancient weapons, armament, military art and cultural life in East and West , 24, p. 209–260.

- GRANT, N. (2020), The Medieval Longsword , Osprey Publishing, Oxford.

- GUILLÉN BERRENDERO, J., SÁNCHEZ, R. (2019), The culture of the sword:honor, duels and other events , Dykinson, Madrid.

- GUILMAÍN ALONSO, (2015), “Francisco Román, master of arms of the Emperor, and his lost Art of Fencing”, in J. IGLESIAS, R. PÉREZ, M. FERNÁNDEZ (eds.), Commerce and culture in the Modern Age . Proceedings of the XIII Scientific Meeting of the Spanish Foundation of Modern History. Editorial University of Seville. Seville, p. 2451-2467.

- GUILMAÍN ALONSO, (2017), “«The sword is the foundation of all shields». Seville fencing in the 1500s”, in J. M. PARODI ALVÁREZ, In Medio Orbe (II):Characters and avatars of the I Tour of the World , Sanlucar de Barrameda, pp:131-141.

- HESTER, J. (2009), “Real Men Read Poetry:Instructional Verse in 14th-Century Fight Manuals” Arms &Armour, 6, pp. 175–183. — (2012), “A Few Leaves Short of a Quire:Is the ‘Tower Fechtbuch’ Incomplete?” Arms &Armor , 9, p. 20–24.

- JAQUET, D. (2020), “Collecting martial art knowledge on paper in Early Modern Germany and China:The examples of Paulus Hector Mair and Qi Jiguang and their reading in the 21st century”, Martial Arts Studies , 9, p. 86-92.

- VALLADARES REGUERO, A. (1999), “Luis Pacheco de Narváez:bio-bibliographical notes.” Newsletter of the Institute of Giennenses Studies , 173, p. 509–577.

- VAN DIJK, C. (2020), “A New Halberd Typology (1500-1800):Based on the Collection of the National Military Museum, The Netherlands.”, Arms &Armour , 17, p. 1-26.

Notes

[1] J. GUILMAÍN ALONSO (2017, 131-132).

[2] GRANT, N. (2020, 4-5, 7).

[3] G. DUEÑAS BERAIZ (2004, 212-213).

[4] V. CIRLOT (1980, 8-14).

[5] C. VAN DIJK (2020, 21).

[6] G. DUEÑAS BERAIZ (2004, 214-222).

[7] J. LUKE (2019, 286).

[8] J. GUILLÉN BERRENDERO, R. SÁNCHEZ (2019, 9-10).

[9] J. LUKE (2019, 283).

[10] J. GUILLÉN BERRENDERO, R. SÁNCHEZ (2019, 53).

[11] J. GUILMAÍN ALONSO (2017, 132).

[12] G. DUEÑAS BERAIZ (2004, 241-251).

[13] J. GUILMAÍN ALONSO (2017, 133).

[14] A. BOMPREZZI (2013b, 778-779).

[15] J. GUILMAÍN ALONSO (2017, 133).

[16] J. GUILMAÍN ALONSO (2015, 2453-2455).

[17] J. GUILMAÍN ALONSO (2017, 137).

[18] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 190-191).

[19] J. HESTER (2012, 20-21).

[20] J. D. AYLWARD (1956, 62).

[21] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 361-362).

[22] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 250-252).

[23] J. HESTER (2009, 181).

[24] D. JAQUET (2020, 87-89).

[25] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 249).

[26] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 295-299).

[27] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 302-305).

[28] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 305-306).

[29] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 302-305).

[30] T. DAWSON, D. JAQUET, K. VERELST (2016, 312-314).

[31] J. GUILMAÍN ALONSO (2015, 2456-2459).

[32] A. BOMPREZZI (2013b, 776-777).

[33] A. BOMPREZZI (2013b, 774).

[34] A. BOMPREZZI (2012, 39).

[35] A. VALLADARES REGUERO (1999,514-515).

[36] A. BOMPREZZI (2013a, 4-5).

[37] A. BOMPREZZI (2013b, 776).

[38] A. BOMPREZZI (2012, 39, 41).

[39] J. GUILLÉN BERRENDERO, R. SÁNCHEZ (2019, 125).