Year 615, the Visigoth king Sisebutus he is carrying out a harsh military campaign, naval and land, against the Roman-Byzantine positions in Hispania. Malaca, Malaga, has just fallen into his power. The combats are fierce and the Visigothic army and fleet are imposing themselves on the Romans at the cost of a bloody tribute.

Despite such triumphs, Sisebuto laments the bloodshed and longs for the days when he could devote himself to the study of astronomy, grammar, and philosophy . In fact, the king composes a poem about the phases and eclipses of the moon to comfort those who see dire omens in these natural phenomena and encourages his friend, the bishop of Hispalis, Seville, Isidoro, to write a new work on astronomy. and nature:De Rerum Natura and to continue writing his monumental Etymologies where universal knowledge should be collected and systematized.

The really surprising thing about the previous picture is not that it occurred in Hispania, but that only there, of all Western Europe, could it occur.

If we really want to understand the extraordinary fact that the existence of sovereigns, politicians, ecclesiastics, writers, etc. meant in Western Europe in the 7th century. like Sisebuto, Isidoro de Sevilla and their successors, that is, men not only able to read and write, but also equipped with sufficient knowledge to safeguard and appreciate the legacy of the classics and participate in meetings such as the Councils of Toledo where scholars Bishops and noble cults of the Aula Regia met to discuss theological problems, of law and politics, it is enough to look at Merovingian France of the 7th century or Anglo-Saxon England of the same period and verify how there the learned kings or they did not exist, in the case of England, or they begin to be an anecdote until they disappear and become a normal thing that the sovereigns could not even write their own name, as is the case of Merovingian France. And it is that, in the words of a French historian, P. Riche, In Hispania at the end of the 6th century and the 7th century it was achieved that “The Aula regia toledana, that is the Visigothic court, had more in common with the Byzantine imperial court than with the Merovingian ”.

This Hispanic singularity is something valuable to highlight. Well, as A. Rodríguez de la Peña points out, the "density" of learned men and the resurgence of Latin letters in the Visigothic Hispania of the 7th century is of an unparalleled force in the West of the time.

Now then, the sudden and dazzling Hispanic cultural awakening was to a large extent propitiated and promoted by a great figure of disproportionate genius and intellect:Isidore of Seville . Let's stop at the figure of him and the importance of him.

Isidore of Seville, transmitter of knowledge

At the beginning of the 7th century, Hispania was taking shape as an idea that specified and conformed to the Regnum Gothorum of which it was no longer but a synonym. Well, as José Carlos Martín wrote:“It seems difficult to maintain, in fact, that for Isidore the history of the Visigoths was not inextricably linked to that of the Peninsula. I think, rather, that for him there were no longer two races or two peoples who shared a territory, Hispano-Romans, on the one hand, and Visigoths, on the other, but a single people of great military and political strength.”

In effect, José Carlos Martín was right. Well, that idea, the one outlined above, was expressed in the texts of the Toledo councils, centuries VI and VII, and very particularly in the transcendental IV Council of Toledo of 633 in whose Canon LXXV the expression “Spaniae Populi ,” that is, “Peoples of Hispania”, to define the political subject over which the King of the Goths rules and who is represented before the monarch by the bishops and nobles of the conciliar assembly.

In fact, Isidore perfectly defined in his Laus Hispaniae that new idea, that new identity that they built and added to each other, Goths and Hispano-Romans. Isidoro's own life was a kind of vital example of this process.

In fact, probably born in Hispalis, Seville, around 556, his parents, Severiano and Turtur, had left their hometown, Spartan Carthage, Cartagena, in 554, so as not to remain under the administration of the restored Roman power in southeastern Hispania brought about by the Recuperatio Hispanic of Justinian in 552. This, that Hispanic-Romans of lineage preferred to live under Gothic rule rather than Roman/Byzantine, was already a sign that something was changing.

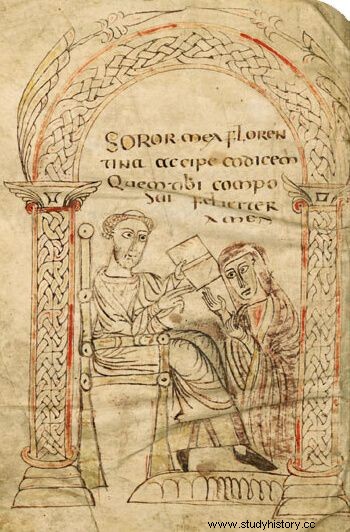

he kept doing it. Isidoro's family, with his three outstanding older brothers -Leander, Fulgencio and Florentia- was going to be one of the most influential in the new "Kingdom of Hispania", as the contemporary Frankish historian Gregorio de Tours repeatedly calls it, which the implacable and brilliant Leovigildo and his temperate and intelligent son, Recaredo, were forging in the extreme West.

Isidore would soon be noted for his erudition and his political skill. Skill that would allow him to successfully overcome the ups and downs of the dangerous Gothic court where the kings succeeded each other between conspiracies and bloody settling of accounts.

Around the year 599 he succeeded his brother Leandro in the episcopal chair of Hispalis, Seville , at that time one of the most powerful, rich and populated cities of the Peninsula and notably influenced kings such as Sisebuto, 612-621, Suintila, 621-631 and Sisenando, 631-636, at a time when the kingdom reached its peak political, military and cultural.

His ability and political influence were manifested in the IV Council of Toledo of December 633 in which Canon LXXV defines the obligations of the king towards the people and of the people towards the king and where the latter is subject to the prevailing law and morality. The monarchy being subject to the conciliar assembly of nobles and bishops who, on behalf of Spaniae populi , "Of the peoples of Hispania" he chose the sovereign and, if necessary, could judge him and depose him.

Isidore of Seville, in fact, perfectly defined what the virtues of the good king should be and with this, and thanks to his powerful influence in medieval Europe, he conditioned the image of the prince that it would be had in the West for the next eight hundred years. Thus, in the Etymologies of it tells us about kings and their power:

But above all, Isidoro was a cultural beacon. A friend of the cultured king Sisebuto (612-621), he undertook at the latter's instigation a series of almost Herculean works: the Etymologies , an entire “encyclopedia” or compendium of the knowledge that the Greeks and Romans had bequeathed to the world; The History of the Goths, Vandals and Swabians and the little appreciated, but surprising and unknown, Universal Chronicle . They were not the only works of his. On the contrary, they numbered in the dozens and dealt with diverse topics ranging from philosophy and theology to biblical exegesis, music, mathematics, numerology, hydraulics, law, astronomy, etc.

Possessor of a very abundant library in which there were works lost to us today, his knowledge and, even more, his attitude towards knowledge and his universal concept of it, made it a bridge between classical antiquity and the Middle Ages . While his taste for the systematization of the knowledge of the ancients and his ability to add it with total naturalness and success to the new cultural context that the Middle Ages already announced, made him one of the great masters of Europe.

Isidore, faced with knowledge, does not adopt a passive role, of a mere transmitter, but rather questions its function and purpose. His reflections on history, grammar, music, politics or good government, etc. they are full of good sense and deep reflection that preludes humanism insofar as it aspires to a full and integrated understanding of man and nature as creations and therefore, as projections, of Divinity.

It is difficult to convey the extent to which Isidore of Seville influenced the learned men of medieval Europe . Monasteries and cathedral schools throughout the West relied on his works and found in them a substantial part of his scholarship and, through it, of his worldview. But although Isidore's works were many that conditioned European thought for centuries and centuries, the truth is that it is in his Etymologies where we find the greatest cause for astonishment and the sum of his intellectual virtues. Well, without a doubt, the Etymologies by Isidore of Seville are the most fascinating work written in Europe between 400 and 1200.

A work for posterity

The Etymologies they are not a mere "encyclopedia," but a complete reflection on the knowledge of the ancient Greeks and Romans and its synthesis with Hebrew literature and the new Christian civilization. Isidore not only collected and synthesized much of the knowledge of the classical world, but also adapted it to the new world that emerged from the fall of the Roman West, thus making that knowledge understandable for medieval man and incidentally, and therefore, saving it in good faith. measure.

The twenty books that make up the Etymologies they are an overwhelming sample of the knowledge that was available in the Visigothic Hispania of the 7th century . The whole of Europe, Europe from the 7th to the 15th centuries, was largely formed by reading these twenty books of the Etymologies . In them we can find disciplines, knowledge and subjects as varied as grammar, rhetoric and dialectics, arithmetic, music, geometry and astronomy, medicine, law, chronology, the Holy Scriptures, the cycles of time , libraries and books, festivals and major trades, the nature of God, the angels, the holy fathers, the hierarchy and organization of the church, the synagogue and Judaism, the life and work of the most famous philosophers, heretics and poets, the study of other religions, news about the peoples of other lands, about their languages, institutions, customs and the relationships that were had with them or where the knowledge of them came from, the study of names, the anatomy of the human being, its malformations and the phenomena linked to it, animals, both familiar and close, as well as exotic and almost fabulous, the elements that made up the universe and matter, the seas, rivers and floods, the geography, the types and elements of urban and rural settlements:the cities, towns, villages, etc., the forms of communication that could be used, the weights and measures, the minerals and metals, the agriculture, war:weapons, tactics, etc., shows and games, different types of boats, fishing, buildings and clothing, food and drinks, household goods, tools...

That totalizing and universalist desire of Isidore of Seville can also be seen in his Universal Chronicle , where, with astonishing naturalness, he hybridizes Greco-Roman, Babylonian and Hebrew traditions and myths with Roman history and the new Christian culture.

But without a doubt, his most influential work during the next eight centuries that passed after his death were his Sententiae , "Sentences", a work of a reflective and moral nature where he addresses issues such as the object and reason for the power of the princes and which marked an entire conception of good government in medieval Europe. An idea that was also reflected in the IV Council of Toledo, to which we have already referred above, as well as in its Etymologies and in which the law remained as a referent and maximum ruler to which even the king had to submit even if he himself had promulgated it. The power of the king was sacralized as it was nothing more than a kind of responsibility that God granted him as Vicarius Dei , that is, intermediary between God and the people or, following a biblical image, as "shepherd" of his people. But at the same time, this divine "order" allowed the subjects to demand good government, respect for the laws and restraint from the king.

Isidore's influence was enormous in his own time and momentous in the centuries that followed. His works were soon copied in Ireland where in the 8th century he was one of the most widely read authors and the highest authority on such varied subjects as geography, grammar, astronomy, etc. His works were also very soon received and copied in Anglo-Saxon England, in northern France, in Italy... And, of course, they had a powerful echo in the Christian kingdoms and in Hispanic al-Andalus.

In short, it can be affirmed that what we can call “Isidorian Renaissance ” was one of the fundamental bases of the later and better known Carolingian Renaissance. And that the great cultural flourishing experienced by Europe during the twelfth to fourteenth centuries also had one of its fundamental roots in the legacy of Isidore of Seville.

Bibliography and primary sources

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologies :Díaz Díaz, M., C. San Isidoro de Sevilla, Etymologies. Madrid, 2000.

- Isidore of Seville, Universal Chronicle :Martín, J.C “The Universal Chronicle of Isidoro de Sevilla:historical and ideological circumstances of its composition and translation of it.” Iberia. Antiquity magazine. Vol 4, 2001, pgs. 199-239.

- Riche, P. (1971): L’éducation a l’époque wisigothique:les institucionum disciplinae. Anales Toledo 3, 1971.

- Riche, P. (1967):Education et culture dans l'occident barbare. VI-VIIIe secles, Paris, pp. 209-221.

- Rodríguez de la Peña, M. A. (2008):The wise kings. Culture and power in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages , Madrid.

- Teillet, S. (1984):Des Goths à la nation gothique. Les Origenes de l’idée de nation en Occident du Ve au VIIe siècle , Paris.