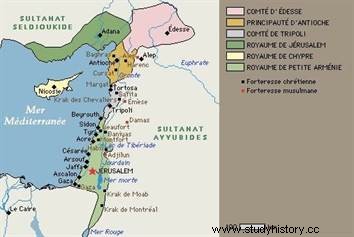

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was a Latin and Christian state of the Middle Ages founded during the first crusade, in 1099, and whose capital was Jerusalem. Disappeared in 1291, it covered present-day Israel, part of Jordan and Lebanon. It was the longest and most extensive of the Frankish states founded by the Christians during the Crusades. The importance of the city, a high place of pilgrimage, was central for Western Christians. It was therefore logical that the kingdom created around it in 1099 was the most important of the Latin states, and that its sovereign had preeminence over the other princes and counts. However, the life of the kingdom of Jerusalem was not going to be easy, and not only because of the desire of the Muslims to take back the city...

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was a Latin and Christian state of the Middle Ages founded during the first crusade, in 1099, and whose capital was Jerusalem. Disappeared in 1291, it covered present-day Israel, part of Jordan and Lebanon. It was the longest and most extensive of the Frankish states founded by the Christians during the Crusades. The importance of the city, a high place of pilgrimage, was central for Western Christians. It was therefore logical that the kingdom created around it in 1099 was the most important of the Latin states, and that its sovereign had preeminence over the other princes and counts. However, the life of the kingdom of Jerusalem was not going to be easy, and not only because of the desire of the Muslims to take back the city...

Kingdom of Jerusalem:a feudal system

It makes sense that the lords who took possession of the Holy City imported their own systems for governing it, and for organizing the realm itself. Most of the masters of Jerusalem are, from 1099, barons from the North of France; they are certainly not of great lineage, but they nevertheless possess the codes and structures, those which began to be put in place and consolidated in the 11th century in the West, and more particularly in the Capetian kingdom.

It should immediately be specified that the kingdom of Jerusalem certainly has a strong symbolic importance, that it is the largest of the Crusader states, but that on the scale of the West, it's no bigger than a decent duchy. Moreover, the modest origin of its lords also relativizes its influence, which is important in the relationship of the kings of Jerusalem with the other great sovereigns, Western or even Byzantine.

It is however a real feudal system that is set up, at least at the highest levels. At the top, therefore, a king from Baudouin I (while Godefroy de Bouillon was, according to his own will, only “advocate of the Holy Sepulchre”); it is a hereditary monarchy which, as in France, excludes women (even if they have their role, as we will see). The life of the sovereign is organized around a curia regis , without real administration, where all the vassals can be present, but where only the decision of the great lords and especially of the king is followed. It is within this court that all political, economic, legislative, military life, etc., is decided, that fiefs are granted, the rules of transmission enacted and the war "voted".

The king predominates thanks to the right of conquest, he holds his power only from God (through the anointing granted by the Patriarch of Jerusalem during the coronation), and therefore is not himself a vassal of a Western overlord, or even of the pope. However, in theory, the sovereign is still elected by the Great according to the will of Godefroy de Bouillon; but from Baudouin I, the monarchy therefore became hereditary in practice, even if the support of the Great remained important. From his coronation, he is declared as "chief lord", that is to say suzerain of the other lords, and therefore at the top of the feudal pyramid. This system works at full capacity until the 1150s, but it quickly cracks because of the first difficulties, to which we will return. Also in the early days, the king claimed suzerainty over the other lords of neighboring states, thanks to the importance of Jerusalem. Apart from under the first two Baudouins, it is not really visible in practice...

At the executive level, apart from the king, the powers are relatively limited:the constable commands the army, assisted by the marshal; the seneschal takes care of financial management, while the chancellor, chosen from among the clerics, has less power than in the West. Finally, the chamberlain administers the royal residence.

Population and settlement of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

As we have seen previously, the Latin States were created despite the massive return of the first Crusaders; the Latin population was therefore very small at the beginning of the 12th century. It is concentrated above all in the cities, even if there are more important traces than one believed for a time in the rural areas. On the eve of the fall of Jerusalem (1187), the Latin population is estimated at around 100,000 souls, gathered mainly in Tyre, Acre and Jerusalem itself (about 20,000 for the latter); a population that could provide around 2,000 knights and 20,000 infantry for the quasi-permanent wars of the time.

This increase over almost a century is due to immigration from Europe. It can be classified according to several waves, located mainly between 1100 and 1150. These populations therefore settled first in the cities, but also to a lesser extent in the rural areas, even creating a few Latin villages. A real system of colonization is organized, but it seems to have stopped with Amaury I (1163-1174).

It was Jerusalem that was the first to be repopulated:its population was partly massacred or reduced to slavery, and in addition Jews and Muslims were prohibited from staying there (only a short pilgrimage is allowed to them). Baldwin I therefore did not hesitate, from 1115, to “deport” Syrian Christians from across the Jordan to come and settle them in the holy city! The proportion of Latins is about one inhabitant out of four in the kingdom; the natives are mostly Muslims, but there are also significant minorities of Syrian Christians of different persuasions (Jacobites, etc.), or even Armenians, some Byzantines and of course Jews.

We will discuss in another "Deus Vult" the nature of the relations between these different peoples (as well as the role of military religious orders), but we can already note that contacts were relatively few between the Latins (including the "Colts", born on the spot) and the "others", but above all that the failure of colonization sounded the death knell in the medium and long term of the kingdom, and of the Latin States as a whole.

A Conquering and Offensive State (1099-1174)

The reigns of Baldwin I (1100-1118) and Baldwin II (1118-1131) are those of conquest and maximum expansion of the kingdom, despite the failures in Syria against Aleppo and Damascus. The difficulties begin with the accession of Zankî, but above all of Nûr al-Dîn, in a context of disputed succession of Baldwin II; he would have transferred his power to a trio composed of his son-in-law Foulques d'Anjou, his daughter Mélisende (whose mother is Armenian) and his grandson Baudouin. This provoked disputes and rebellions, but above all the creation of two factions opposing the two spouses, Foulques and Mélisende! This does not prevent the first from reigning, even if the second is considered more legitimate as the daughter of the deceased king; thus, Foulques consolidates the defenses in the South against the Fatimids, and in the North against Zankî from whose clutches he saves Antioch.

When he died (a hunting accident) in 1143, his son Baldwin III was too young and it was therefore Mélisende who ensures the regency. She showed great skill by relying on a few great lords (such as the Prince of Galilee, Elinard) and by creating an administration parallel to that of the king. Very quickly, she openly opposes her son, causes his failure in his attempt to help Edesse (she has taken as vassals the main lords who could have helped him, enjoining them not to respond to Baudouin's call III), and blames the failure of the Second Crusade, while Louis VII and Conrad III followed the advice of barons close to Mélisende, causing the rout in front of Damascus!

When he died (a hunting accident) in 1143, his son Baldwin III was too young and it was therefore Mélisende who ensures the regency. She showed great skill by relying on a few great lords (such as the Prince of Galilee, Elinard) and by creating an administration parallel to that of the king. Very quickly, she openly opposes her son, causes his failure in his attempt to help Edesse (she has taken as vassals the main lords who could have helped him, enjoining them not to respond to Baudouin's call III), and blames the failure of the Second Crusade, while Louis VII and Conrad III followed the advice of barons close to Mélisende, causing the rout in front of Damascus!

In 1150, it was at its peak but it cut itself off from large families like the Ibelins; it also highlights his other son, Amaury, who becomes Count of Jaffa. It was a real civil war that shook the kingdom until 1152, but against all expectations it was Baldwin III who emerged victorious; he forced his mother to retire to Nablus where she died in 1161. The king managed for a time to contain Nûr al-Dîn, he even took Ascalon in 1153, but he then had to face conflicts between Latin lords, whose famous Renaud de Châtillon. The basileus Manuel I Comnenus did not need to be asked to appear as a mediator, then exercising a quasi-protectorate over the kingdom of Baudouin III, who married his daughter Theodora (she received St-Jean d'Acre as dower)...

Amaury succeeded his brother (probably poisoned) in 1163, and it was Egypt that was the center of his interest. From 1163, the king intervened in the quarrels around the Fatimid vizirate (facing a weakened caliphate), but he had to regain his kingdom under the threat of Nûr al-Dîn. In 1167, he sees with concern a man of Nûr al-Dîn, Shirkûh, settle in the vizirate in Cairo, and he decides again to attack Egypt; if he fails in front of Alexandria (defended by the nephew of Shirkûh, a certain Saladin), he still manages to obtain the payment of a tribute from the Egyptians.

However, despite this relative failure, Amaury I did not give up on the conquest of Egypt, which he considered the key to the Holy Land:he tried to obtain at first the support of Byzantium (he also married a daughter of the emperor, Marie Komnène), but he did not wait for the Greek fleet and failed again in 1168. The situation became complicated:Nûr al-Dîn threatened the eastern borders of the kingdom of Jerusalem, and in 1169 it was Saladin who took the reins of Egypt... The latter became the main enemy of the Franks on the death of Nûr al-Dîn in 1174.

The Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

A year later (after the regency of Raymond of Tripoli), Baudouin IV succeeded Amaury I, who died of typhus in 1174, while he was preparing a umpteenth expedition against Egypt, this time supported by the Normans of Sicily. The king is stricken with leprosy, which will mark his tragic destiny, but also make him a legend. Because his illness did not prevent him from being a great king:he first strived to contain the Saladin threat, which he managed to defeat at Montgisard in 1177. The Ayyubid sultan signed a first truce in 1180, but the provocations of Renaud de Châtillon the following years forced him to attack again, while unifying the Muslims after the capture of Aleppo from the sons of Nûr al-Dîn in 1183. Baldwin IV again managed to stop him and obtain a new truce, but he died of leprosy in May 1185.

The vain dream of a new kingdom

Despite the fall of its capital, the kingdom as such is supposed to still exist…Guy de Lusignan (freed by Saladin), king without a kingdom, takes advantage of the arrival of Conrad, but especially of the Third Crusade, to set up the seat of the kingdom at St-Jean d'Acre (taken over from Saladin in 1191). He enjoys the support of Richard Coeur de Lion, while his rival Conrad has that of Philippe Auguste; but from 1192, most of the barons sided with Conrad, and even the King of England had to let go of Guy. The latter recovers Cyprus, and Conrad of Montferrat becomes king of Jerusalem…in Acre! He does not have time to take advantage of it because he is assassinated the same year (an order from Saladin is mentioned).

The kingdom of Jerusalem then passed from hand to hand, from the Lusignan family to the Ibelin family, and we had to wait for the crusade of Frederick II (which we will discuss in a future “ Deus Vult”) so that for a time (between 1229 and 1244), Jerusalem would be returned to the Latins by the Treaty of Jaffa. But the fall of the Ayyubids leads to the reconquest of the holy city by the Muslims. The Frankish kingdom is slowly dying , torn by internal tensions and the appetite of the Genoese, the Venetians and then the Angevins. It is without difficulty that the Mamluks of Baybars complete it by taking St-Jean d'Acre on May 18, 1291, thus signing the end of the Latin States.

Bibliography- J. PRAWER, History of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, CNRS, 2007 (1 era edition, 1969).

- M. BALARD, The Latins in the East, 11th-15th century, PUF, 2006.

- G. TATE, The East of the Crusades, Gallimard, 1991.

- C. CAHEN, East and West at the time of the Crusades, Aubier, 1983.