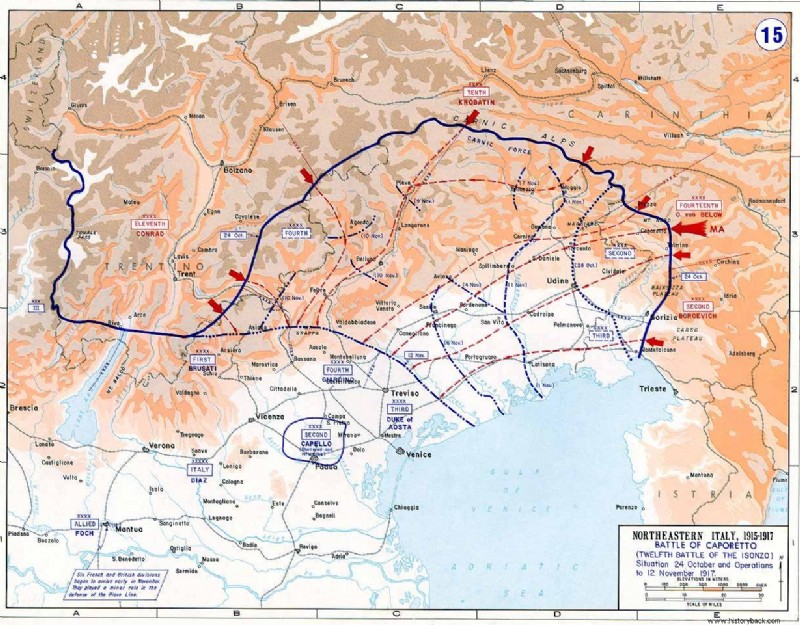

The battle of Caporetto is one of the greatest victories of all time, achieved against a stronger opponent in extremely difficult terrain. The Italian 2nd Army held an extensive frontal sector south of Gorizia.

This particular army had won the laurels of the 11th attack of Iszonso, which was successful for the Italians. It was the strongest Italian army with nine army corps under its command and 24 divisions, on a front of 60 km.

Unwarranted optimism?

Both the commander general Capello and the Italian commander-in-chief Cadorna therefore had every reason to look to the future with optimism. Opposite it was initially the Austrian 2nd Army of Izontso and the also Austrian 10th Army.

The latter withdrew further west, leaving room for the new mixed Austro-German 14th Army. Even after this new arrangement of the front, however, the Italian army alone had almost equivalent forces to the two Austro-German armies – 24 Italian infantry divisions against 18 Austrian and seven German.

The problem for the Italians was that they had their center of gravity turned to the east, towards the sector of Gorizia and the lower Izonzo. Six of the nine army corps of the Italian 2nd Army were lined up there, leaving three to guard the alpine sector of the front, some 30 km long.

It was not unreasonable, however, for the Italian command to expect the eight divisions of the sector to defend with relative ease 30 km of mountainous terrain, which, in its view, could not be exploited by the enemy. And in this observation the Italian administration did not seem to be mistaken.

The difficulty of the terrain, combined with the little cover it afforded the opponents, who held positions lower than the Italians, should not have allowed the necessary concentration of material and personnel to launch a large-scale attack.

Italian soldiers .

Thus a feeling of security for the specific sector was born in the Italian staff. However, in war there are no positions. Thinking exactly like this, the Austrians and Germans decided to attack exactly where they did not expect them, in the alpine sector, on a front of less than 30 km.

Attack

The plan of attack was the product of the cooperation of two generals experienced in mountain fighting, the German General Kraft and the Austrian Lt. General Kraus. The planned attack had to surprise the enemy, who at that time of the year – mid-autumn – had another reason not to consider the possibility of launching an attack in the Alpine sector possible.

The Italians had even withdrawn some of their divisions from the front line, leaving only four to guard the sector, with an average front sector per division of 7.5 km. Another four divisions of the Italian 4th, 27th and 7th Army Corps were held in reserve, some kilometers behind the front line.

German raid section before the attack

The Austro-German plan was simple. Enjoying a numerical superiority of 5:1 in the areas of attack and qualitative superiority in general, Kraft and Krauss planned to attack along the upper Iszonso valley with the aim of capturing Caporetto and first dislocating the left wing of the Italian 2nd Army .

If they could also capture the Stoll and Kolovrat heights, which formed the western arm of the Black Mountain range, nothing could stop them from dismembering or encircling the entire Italian army, forcing the Italian Army as a whole of retreating behind the river Po.

The Italians, however, had warnings about the coming blow, but they ignored them. Commander-in-Chief Kadorna, reacting to the information, contented himself with sending two infantry regiments to the threatened sector.

Crash

Fatefully, when the Austro-German bombardment began at dawn on October 24, the Italians, staff and soldiers, suffered their first unpleasant surprise. On the morning of October 24, Kraus's Austrians attacked first, broke through the Italian positions and almost captured the Stoll hill.

In the central sector, the Alpinist Corps, led by the immovable and fearless lieutenant at the time, Erwin Rommel, managed to move as far as Kolovrat, opening the way for the 12th Silesian Division to Caporetto, which was captured the same day.

It was not until the afternoon of the 24th that the Italian headquarters began to realize what had happened. She had lost contact with three of her four front line divisions and knew that the fourth, the 50th, had been destroyed.

Italian prisoners of war.

Cadorna ordered the immediate dispatch to the threatened front of five divisions and another four in a second year. However, these troops came upon fugitive Italians, mixed with them and panic soon prevailed.

This was helped by the Germans and Austrians who appeared everywhere with deep penetrations, giving the impression to the Italians that their front had completely collapsed.

But it wasn't exactly like that. Simply, the Austro-German raids, taking advantage of their terrain, moved through the mountains, overrunning the Italian positions in the valleys, something similar to what the Greek Papagos army did in 1940-41 in Northern Epirus.

Panicked, the Italians then fled in disorder, just 28 hours after the start of the attack, an unprecedented event by the standards of the First World War. They stopped only after crossing the Po on November 7, 1917 and after being reinforced with French and British troops.

Within three days they had lost the territorial gains of two years of fighting, along with more than 300,000 men and 3,000 guns.