Entry taken from the book "The Plantagenet".

History is full of moments in which an unforeseen or casual event caused a change in the course of events that involved radically altering the historical future of a country or even the world order. If ever there was a case in which a host of unforeseen circumstances came together to change the course of a kingdom's history, it is undoubtedly the birth of the Tudor dynasty.

From a dowager queen who, altering her traditional role, fell in love with a Welsh nobleman, to a family branch of bastard origin who reached a throne from which they had been removed by decree, going through a dynastic war in which the crown changed hands several times and beheaded the various branches of the royal family, a marriage that proved its usefulness thirteen years after it was celebrated, or a decisive battle in which an entire contingent changed sides and sentenced to death the last English king to fall on the battlefield.

And, above all, a girl of noble origin and rich heiress who was passed from husband to husband like a hunting trophy and who, as a woman, fought tirelessly for the your child's rights. An offspring he had when he was barely thirteen years old, whose father had died before he was born and who spent his youth in exile. This is the story of Margaret Beaufort and the birth of the Tudor dynasty.

1.- Catherine de Valois, the French princess who changed the history of England

Catherine, born in 1401, was the daughter of the king Charles VI of France, known as the Beloved, but also as the Fool due to his personality disorders. At the Battle of Agincourt (1415) the English King Henry V defeated the French army against all odds. From that moment on, all of France was at his mercy and Charles VI was forced by the 1420 Treaty of Troyes to recognize Henry V as heir and to give him his daughter, Catherine of Valois, in marriage. In this way, the kingdoms of France and England would be unified in a single crown.

But Henry V died in 1422, not before he had time for his marriage to Catherine to give him an heir, the future Henry VI. The queen dowager seemed destined to fade into history in the role of her queen mother. And so it would have been if her path had not been interposed by a love that would change the history of England. The name of the girl in love with her is enough to explain why:Owain Tudur or, as the English scribes renamed him, Owen Tudor.

Owen was a minor Welsh nobleman who had found a job in the household of King Henry VI. There, he and Catherine of Valois fell in love and from their union (depending on sources) four or five children were born. It seems they got married in secret.

When Catherine died in 143, Owen was imprisoned by the regents of the kingdom (the king was still only 13 years old). But when Henry VI came of age, he freed Owen and his children by his mother, his half-brothers Edmund and Jasper Tudor. In 1452 he made them Earls of Richmond and Pembroke, respectively.

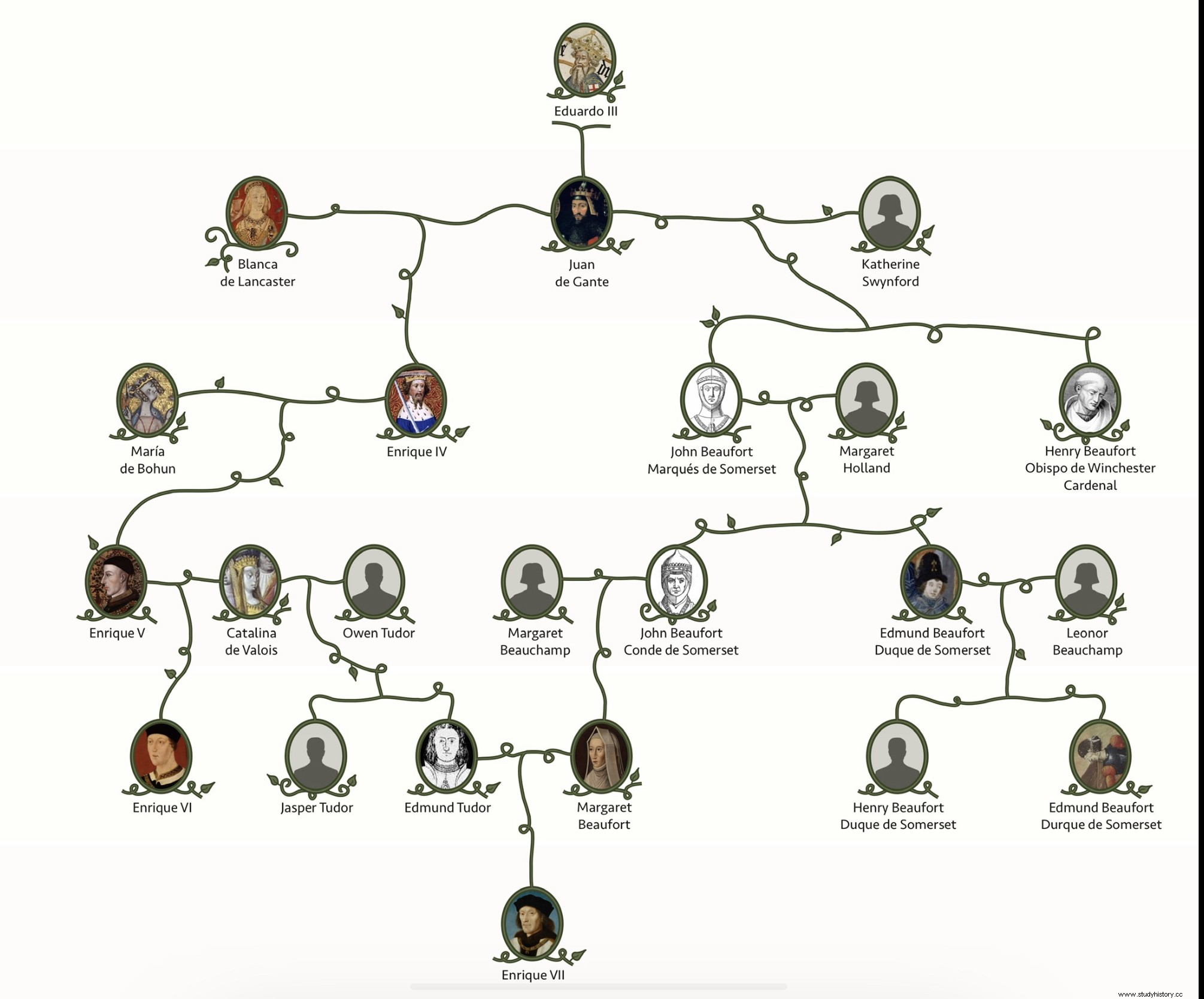

2.- The Beauforts, the branch of bastard origin that was removed from the throne by royal decree

To know the origin of the Beaufort family we have to start from the figure of the English prince John of Ghent, son of King Edward III and Duke of Lancaster (hence the name of the house to which his descendants belonged). From his marriage in 1359 with Blanca de Lancaster, Henry IV was born, who proclaimed himself king of England in 1399, dethroning his cousin Richard II. Juan de Gante married in second nuptials in 1371 with Constanza de Castilla. From this marriage was born Catalina de Lancaster, first princess of Asturias, queen of Castile and grandmother of Isabel la Católica.

John of Gaunt had a mistress named Katherine Swynford. From this union four children had been born during the 1370s who adopted the surname Beaufort (it was the name of one of their father's continental possessions). The fact that all four were born out of wedlock to a married man made these illegitimate offspring ineligible to inherit their father's family titles and estates.

When his wife Constance of Castile died in 1394, Juan decided to remarry. Although he could have chosen any marriageable young European royal, he chose to honor his longtime faithful companion and lover, Katherine Swynford. The couple married in Lincoln on January 13, 1396. John of Gaunt had only one legitimate heir, Henry Bolingbroke (the future Henry IV), and he decided that it was important for him to have the support of his half-brothers without weighing them down. because of its stigma of bastardy.

The illegitimacy of a son not only deprived him of the possibility of inheriting his father's titles and estates, but also of obtaining preferential treatment in the event that they chose to do career within the church. To solve both obstacles, it was necessary to request recognition of the legitimacy of children born before marriage by civil and canon law.

John of Ghent addressed both the pope and the English Parliament to get the four offspring of his union with Katherine Swynford legitimized. Papal recognition was granted in September 1396. And Parliamentary recognition in January 1397, when a law declared that King Richard II, in the exercise of his power and with the ratification of Parliament, granted the children of John of Ghent and Katherine Swynford are considered legitimate descendants of their father for all purposes. This included the right to access "all honours, dignities, pre-eminences, properties, degrees and public and private offices, both perpetual and temporary, noble and feudal, by whatever name they may be designated, whether dukedoms, principalities, counties , baronies or others”.

As we have pointed out above, in 1399 the eldest son of John of Gaunt and White of Lancaster, Henry IV, half-brother of the Beauforts, had acceded to the throne. When the question of his legitimacy was raised in 1397 it seemed unlikely that descendants of John of Gaunt were in the line of succession to the throne (John was the third son of Edward III). However, when Henry IV usurped the throne in 1399, his (already legitimized) half-siblings were much closer in that line of succession.

In 1407 the eldest of the Beauforts, John, then Earl of Somerset, petitioned Parliament to confirm the legitimacy of his family. His request was approved, but a small but very significant variation was made on the original text. They were granted access to "all honors, dignities, except royal dignity , pre-eminence…».

The historian Nathen Amin draws attention to an important aspect:the initial resolution of 1397 had been approved by an act ratified by Parliament. Any modification to its content should have followed the same procedure (either through its repeal and replacement by a new law, or through a regulation that modified the previous one). However, the addition of 1407, although it was sanctioned by Enrique IV, did not go through the process of parliamentary ratification.

For the cited author, this nuance means that the exclusion of the succession line of the Beauforts was not validly established and that, therefore, what should prevail was the law of 1397 where they were recognized the right to access any dignity, including the royal. This would mean, according to Amin, that all the descendants of the Beauforts would have a right to the English throne.

3.- Margaret Beaufort:birth and first marriage commitments

Margaret Beaufort was born on May 31, 1443. When she was only one year old, her father, John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, died under mysterious circumstances after a disastrous campaign in France. Many rumors pointed to her suicide because she was going to be held accountable for the excesses and errors committed in France, but there is no irrefutable evidence of the cause of death.

Margaret did not inherit the title from her, which passed to her father's brother, Edmund Beaufort. When she was six years old she arranged her marriage to John de la Pole (then eight years old), but the union was never consummated. John's father and Duke of Suffolk, William de la Pole, fell from grace and was scapegoated for the loss of English holdings in France.

De la Pole had been the architect of the signing of the Treaty of Tours, on May 22, 1444, by which the marriage of Henry VI of England with Margaret of Anjou. The English could forgive the fact that the bride came without a large dowry under her arm, despite being the niece of the King of France and her father displaying the impressive but empty titles of King of Naples and Sicily and even wielding a supposed right to Jerusalem throne. What the English did not forgive De la Pole for was that he ceded to the French king with a stroke of the pen the territories of Anjou and Maine that they had shed so much blood to preserve and from which the enemy used as a launch pad to reconquer Normandy and Brittany.

The Marquis of Suffolk's protests about the impossibility of winning a war that his king did not want to wage and for which he had no funds were useless. De la Pole fell into disgrace (he would end up being assassinated on his way to exile to which Parliament condemned him), his son's (unconsummated) marriage to Margaret Beaufort was annulled and the girl was left in the custody of the king's half-brothers, Jasper and Edmund Tudor.

The Tudors were, as we have seen, brothers on the mother's side of King Henry VI and, despite the court scandal, he treated them with great generosity. Therefore, when he tried to find accommodation for the orphan Margaret Beaufort, he decided to marry her to her stepbrother Edmund Tudor. After all, the Beauforts were also descendants of Edward III. In this way, the Tudors became part of the Lancaster family branch.

It was time to reinforce the side with new blood of the Lancastrians. In 1453 Henry VI went through a period of loss of his mental faculties (inheritance from his maternal grandfather Charles VI of France) and the regency of the country became occupied by the Duke of York, Richard Plantagenet. Late in 1454 the king regained his lucidity, restored Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset and Margaret's uncle, (also a Lancastrian) to head the council, and summoned the Yorker to account for his deeds. This refused and there were several clashes between the supporters of the York (who based their right to the throne on being descendants of the second and fourth sons of Edward III) and those of the Lancasters (descendants of the third son of Edward III). Hostilities had first broken out on May 22, 1455 at St. Albans, where the Duke of Somerset died. It was the beginning of the war of the Roses.

Meanwhile, Margaret Beaufort and Edmund Tudor had begun their conjugal life, despite the fact that she was only twelve years old. But Edmund had to come to the defense of his half-brother Henry VI to face the York party in Welsh lands and there he was taken prisoner by a Yorkist gentleman, Lord William Herbert. This transferred Edmund to Carmarthen Castle, where he contracted an illness and died in November 1456.

At just thirteen years old, Margaret was left a widow; and she was also pregnant. On January 28, 1457, her son, whom she named Henry, was born at Pembroke Castle. Miraculously for the time, despite her young age and weak physical constitution, both her mother and her son survived. In the words of her confessor, John Fisher, "it seemed a miracle that someone could be born from such a small character." It is believed that due to the damage sustained during her birth, Margaret was left sterile. In any case, she had no more children.

The first years of the boy's life were spent in the same Pembroke Castle, residence of Edmund Tudor's brother, Jasper. And from there we will pick up the second and third entries in this series.

Images| Wikimedia Commons.

Family tree drawn up by Ventura Contents for the book What Shakespeare didn't tell you about the Wars of the Roses.

Daniel Fernandez deLis. The Plantagenets . Madrid, 2021..

Daniel Fernandez deLis. What Shakespeare didn't tell you about the Wars of the Roses . Madrid, Libros.com, 2020.

Dan Jones. The Hollow Crown. The Wars of the Roses and the rise of the Tudors. London, Faber &Faber Limited, 2015.

Plantagenets, The Kings Who Made England . London, Ed. William Collins, 2012.

Peter Ackroyd. A History of England. Volume I (Foundations). London, Ed. McMillan, 2011.

Roy Strong. The Story of Britain. London, Pimlico Ed., 1998.

Simon Schama. A History of Britain. London, BBC Worldwide Limited, 2000.

Derek Wilson. The Plantagenets, The Kings That Made Britain . Ebook edition, London, Quercus Edition Ltd., 2014

Nathan Amin. The House of Beaufort. The Bastard Line that Captured the Crown. Stroud, Amberley Publishing, 2017.

Elizabeth Norton. Margaret Beaufort, Mother of the Tudor Dynasty. Stroud, Amberley Publishing, 2011.

Thomas Penn. Winter King, The Dawn of Tudor England. London, Penguin Books, 2012.

Alice Carter. The women of the Wars of the Roses. Ebook Edition, Editor Alicia Carter, 2013.