Today, December 4, is the anniversary of the death, in 1214, of the King of Scotland, William the Lion. This monarch played an important role in relations between England and Scotland, which have traditionally been complicated. The last episode of this story took place in 2014 with the Scottish independence referendum that ended with the victory of those in favor of staying in the United Kingdom. Another of the best-known moments (largely thanks to the film Braveheart) of the disagreement between the two took place with the process for the election of the new Scottish king that took place after the death of King Alexander III in 1286 (see the entry dedicated to the situation that his death caused).

The election of the new king was arbitrated by Edward I of England and the name of the King of Scotland, William the Lion, was heard repeatedly. There were two reasons why he was summoned. The first, because the main candidates for the throne were his descendants. And the second, which is what this entry focuses on, because during his long reign (1165-1214) the vassalage relationship between the two kingdoms was raised on several occasions.

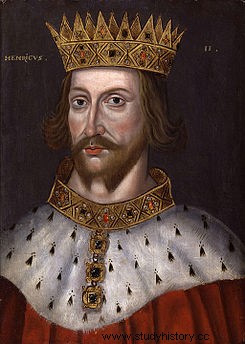

Let's situate ourselves:in the spring of 1174. Henry II, who was facing a widespread rebellion on the continent of his subjects led by his own sons Henry the Younger, Richard and Godfrey and sponsored by his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine and her first husband, the King of France Louis VII, was forced to return to England, where the situation had become complicated after an invasion by our protagonist, King William of Scotland, who obtained several victories against the English army in Northampton, Nottingham and Leicester.

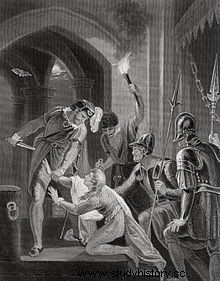

Henry's first action in England was a theatrical hit effect. Mindful of the widely held opinion that his troubles were divine retribution for the murder of Thomas Becket, he headed straight for Canterbury, where like any other pilgrim he reached the martyr's grave and, after a long tearful prayer, and protests of innocence, he swore that he had nothing to do with the archbishop's death but asked to be acquitted of his guilt for the words he spoke that caused his murder. He then fasted and did penance for three days, eventually being flogged by several of the community's monks. All this, in the presence of numerous witnesses to make it clear that he had settled his debt with Becket and that the saint had forgiven him for his sins.

And his action seemed to pay off:he was still in Canterbury when news reached him that his army had defeated King William of Scotland at Alnwick, taking prisoner to the monarch himself. In less than a month the rest of the rebellious barons in England had either been defeated or had surrendered to the king, who in August was able to return to the continent. There, his swift return took Louis of France, Philip of Flanders, and Henry the Younger by surprise, who had invaded Normandy in the hope of taking the capital, Rouen, before the return of the King of England. When their plans failed, they lifted the siege and Louis of France requested to start peace talks.

The peace conference was held in Montlouis. After showing the world his strength against a formidable alliance of enemies, Henry II could afford to show generosity to his rebellious sons, but not to the Scottish monarch. Henry forced him to sign in December 1174 the Treaty of Falaise, by the mercy of which several castles were confiscated. The Scottish monarch and nobles were forced to take an oath of allegiance to the English king and to recognize the kingdom of Scotland as a vassal of England. Later, once free, the King of Scotland reneged on his oath claiming that he did it under duress.

Years later, the issue was brought up again before the new English king, Richard the Lionheart. The English monarch was more concerned with his aspirations in the Holy Land and his problems on the continent with Philip of France than with the situation in the largest of the British Isles. Of the ten years of his reign, he only spent six months in England, which he saw only as a source of income for the Crusades. A chronicler put in his mouth the phrase "he would sell London if he found a buyer." Whether or not he said those words, they clearly respond to Lionheart's thoughts. If that's what he thought of England, he cared even less what happened to Scotland. Again with fundraising as the basis of his actions, he contacted William the Lion and agreed with him to give up his hard-earned tribute to his father in exchange for a considerable sum of money to finance his crusade.

And the subject came up again with the third king of England with whom he lived, Juan sin Tierra. Rumors had reached Juan of an alliance between France and Scotland to attack England. With the excuse of persecuting a noble family, the de Braose, who had rebelled against him and had accused him of murdering his nephew Arthur of Brittany, John the Landless invaded Scotland and forced William the Lion to sign the Treaty of Norham, by which he again recognized the King of England as feudal lord of Scotland; This ended with the threat of a joint invasion with France.

This was not the end of the problems between England and Scotland either… but that is another story, which William the Lion no longer starred in and which we have referred to in the entries dedicated to the battles of Stirling Bridge, Falkirk and the problems between Robert Bruce and John Comyn.