At some point in our lives we are all Pre-Raphaelites . Without suspecting it, we imitate that same cliché of silly adoration towards the languid and archaic beauty that emanates from the paintings of the somewhat eccentric artists who altered Victorian England. Deliberately mystical, medieval, dreamers. That Brotherhood of painters and poets that barely lasted five years in the mid-nineteenth century has had, despite the disdain of the Academy, an overwhelming influence on popular culture. The Pre-Raphaelites were singular, modern and pure types who were no longer moved by classical art. His obsession, thanks to an unshakable faith in the primitive, was to return to the uncorrupted nature prior to Raphael's worldview. , the huge Italian painter of the Renaissance. Paradoxically, his desire for fidelity to a locus amoenus primary, of rescuing physical love from the religious tables of the Middle Ages, condemned them to an excessive artifice, to a sublimation of beauty that would end up becoming sinister.

Ophelia (1852) – John Everett Millais (founder of the Brotherhood). Lizzie Siddal Model

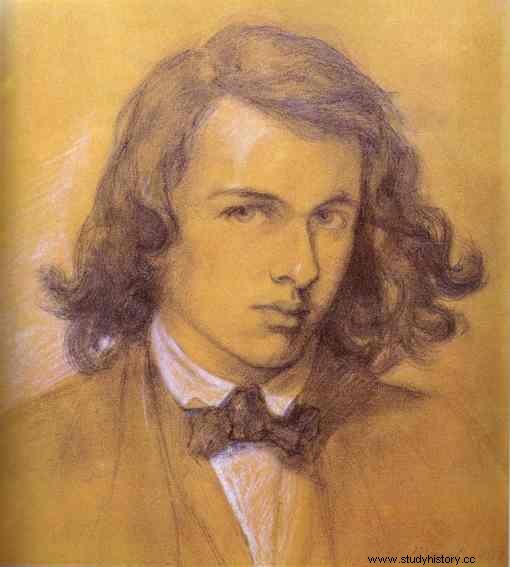

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882) was the most venerable representative of that saga of artists corrupted by the uncorrupted, poisoned by symbolism, lukewarm worshipers of lividity. Due to his eccentricity in a world of predictable conventions, his art is today the most recognizable for us, citizens of the 21st century. The Internet is full of reproductions and versions of his portraits of women (always previously and tragically loved women) and also of translations of his poems.

Self-portrait (1847)

Imagine, it's not complicated, the Victorian era:class hatreds, industrial revolution, bloody inequality, artificial customs destined solely and exclusively to divide the world between aristocrats and workers, peasants and upper bourgeoisie. (Good) taste as the most direct and cruel way to distinguish between rich and poor. In that world of double and even triple standards, the artistic career of a cultured and dreamy son of Italian immigrants developed. Rossetti was condemned, by name, to be an artist. And the art reciprocated.

Wrote the great art historian Ernst Gombrich that Rossetti was more than just a romantic. He wrapped his life and his painting (and his poems) in sleep. And his muses did not represent, like those of the homonymous poet, beatific visions, but " an eroticism charged with condemnation with which to betray the suffocating confinement of Victorian aesthetics ”. Rossetti never cared about anatomy or perspective. He also did not mind stealing the girlfriends of his artist friends, in the case of William Morris, or descending to the grave of his beloved to unravel poems from her hair and then publish them.

Yes. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, visionary whose mental faculties were never fully aligned, who tried to commit suicide a couple of times by ingesting bottle after bottle of laudanum (funeral fashion of the time, like selfies or designer drugs today), He arrived in a moment of severe alienation to rummage in the grave of one of his great muses, Lizzie Siddal , an especially beautiful and especially sickly working-class young woman. A diamond in the rough for the tender eyes of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Blessed Beatrix (1864-1870) – Rossetti. Lizzie Siddal Model

Siddal joined tuberculosis with a passion (also) for laudanum and a miserable life. A cocktail that, together with the little attention Rossetti seemed to pay her —with the exception of the time she dedicated to him in her portraits and in her bed— inclined her to suicide. Rossetti, martyred by guilt, buried next to his body most of the poems he wrote during his beloved's life. But years later, when the sorrow subsided, repentance arose. She obtained official permission to exhume her body and rescue from the clutches of death (well, literally from her hair) the poems that would make up her first collection of poems published in 1870. The book, of course, was a success. Q>

Rossetti lived until his death in a stately Tudor-style house. In accordance with his level of escape from the realm of reality (that interrupted dream of art) he turned the garden of the mansion into an exotic zoo. On the evergreen grass —just as intensely green as in his paintings— ranged freely from a zebu to a kangaroo or a white bull, which the painter apparently fell in love with for having the same look —bovine, it is assumed— that one of his lovers (Jane Morris ). Yes, he must have hit the symbolism hard.

Proserpine (1874) – Rossetti. Model Jane Morris

Collaboration with Nacho Segurado

Fonts :Art History – Ernst Gombrich, Secret Lives of Great Artists – Elisabeth Lunday, Romanticism and Art – William Vaugham