This archenemy, so little known in our days, was a true villain in the eyes of Rome and whose affront lasted in the collective memory for many centuries. Perhaps his deed would be more popular now if he had not lived with characters of the stature and importance of Hannón and Hamilcar Barca , and he would not have suffered the envy and ostracism of the Suffetes of Carthage.

Xantype (in Greek Ξάνθιππος, Xánthippos listen)) was a mercenary chief, most likely of Lacedaemonian origin, who entered the service of Carthage during the First Punic War. Let's get some background:the first great armed conflict between Carthage and Rome was fought mainly in the lands and waters of Sicily. We are in 256 a. C. Nine long and hard years of war had already passed when the Roman Senate decided to put an end to the conflict by moving the theater of operations to Carthage itself. Until that moment, without decisive victories or defeats, the war was tilted on the Italian side. Virtually all of Sicily except the current provinces of Palermo and Trapani were in Roman hands and the elements and two major naval battles, the first at Mylae (today Milazzo) and the second in the Cape Ecnomus (now Poggio di Sant'Angelo, in Licata) had sent a large part of the Carthaginian fleet to keep Neptune company.

Cape Ecnomus

Following the crushing Roman victory at Cape Ecnomus , the result of a frustrated attempt by the Punic navarcas to stop the imminent Roman invasion of Carthage, the two consuls of 256 a. C., Marcus Atilio Régulo and Lucius Manlius Vulsus , landed their legions at Clypea (also called Aspis, today Kélibia, in Tunisia) after having lost only twenty-four ships against the thirty sunk and seventy-four captured from the enemy off the Sicilian coast. The city fell without too many setbacks and the Romans expanded throughout the area causing fear among the native population. The Council of Carthage commissioned three of its most noble members ―Bóstar , a certain Hamilcar (not Hannibal's father) and Hasdrubal Hannón ― to take the troops out of the city and crush the Roman army, but these, avoiding the great plains where their elephants and cavalry had an advantage, headed towards a mountainous area where Regulus did not hesitate to attack them. The Battle of Mount Addis (today Oudna) was a new setback for the Punics, who lost five thousand infantry, five hundred horsemen and an indeterminate number of elephants, compared to the ridiculous casualties suffered by the Roman legions.

That victory encouraged the invaders even more and, before the end of the year, the consul arrived in his raids to a distance of only a day from Carthage and neighboring Numidia rebelled against the city taking advantage of that chaos. Distraught by this deadly pincer, the Council sent emissaries to the consul in search of a mutually beneficial pact, but the terms Regulus laid out were so humiliating and intolerable that the Council decided to maintain hostilities to the bitter end. With this tremendous panorama our protagonist entered the scene. I have already commented at the beginning that Xantype he was, presumably, a mercenary of Spartan origin, willing, like any soldier of fortune, to put his talent and courage at the service of the highest bidder, and, in the year 256 a. C., the suffetes of Carthage were probably the richest and most pressing patrons of all the western Mediterranean. He wasn't the only expatriate Spartan; At that time, the city and region of his birth were in chaos caused by the fights between the Achaean cities and the invading Macedonia. Sparta had always been a famed school of warriors, and perhaps Xanthippus best sold that quality to the needy Carthaginian Council.

It was on the way back from one of his trips in search of new recruits for the mercenary army of Carthage when Xanthippus he found himself with that bleak panorama. Well aware of how the Addis disaster had happened and the number of troops and cavalry involved in the battle, he stood before the Council and publicly accused the three Punic commanders of incompetence. As Polibius left us written in the Histories of him , this told them:

The Carthaginians were defeated not by the Romans, but by themselves, due to the inexperience of their leaders

After that acid argument, he ended up offering himself to command the armies, I presume not for a small price, and expel the Romans from Carthage. The Council, perhaps goaded by popular outcry, perhaps desperate in the face of Roman pressure, agreed to the risky request of that adventurer, who surely asserted his proven instruction in the art of war and his Lacedaemonian origin, cradle of the most bizarre warriors of the ecumene. The rest of that year and the beginning of the next Xantype He dedicated it to instructing his new troops, carrying out maneuvers in the plains, a place that he had pointed out as ideal to face the Romans and thus be able to deploy the best weapons that his ineffective predecessors had not been able to take advantage of given the steepness of the terrain:the phalanx and light cavalry.

In the spring of 255 a. C., Marcus Atilio Régulo he resumed operations, this time only because his fellow consulate Manlius had returned to Rome over the winter, he remaining as acting proconsul at the head of his huge army. Xanthippus left Carthage with his troops inland, twelve thousand Phalangist foot soldiers and Greek mercenaries, four thousand horsemen and a hundred war elephants. Regulus had more troops, about fifteen thousand legionnaires and five hundred horsemen, to which a good number of auxiliaries would have to be added, so the Roman became brave and took the bait, planting himself on the banks of the Bagradas river (today Medjerda) and presenting pitched battle. One of the most notorious massacres of the Roman army took place on that plain that Xanthippus liked so much. The Lacedaemonian charged against the narrow Roman manipulative line with his elephants, in turn launching his numerous cavalry from the flanks, which put the enemy to flight without too much trouble and surrounded Regulus from the rear as Hannibal would later emulate. Although at first the Roman managed to disrupt the enemy's right flank, crushing the eight hundred defending Greeks, strategy soon won out over tactics.

Looking for a more popular simile in our recent imagination, that pitched battle was the Little Big Horn of Regulus, as arrogant and reckless as General Custer, because the Roman infantrymen perished surrounded by their enemies and with no escape options, crushed by the elephants, the arrows and spears of the cavalry and the sarissas of the phalanx. The two thousand Romans who managed to reach Addis they were the only ones who escaped the carnage. The rest of his companions died in that dusty valley or were imprisoned. The sources speak of two thousand five hundred captives, among whom was the consul himself.

For a short time Xantipo was able to enjoy of his resounding success. As in our beloved Spain, if the envy had been Olympic, the Suffetes of Carthage would have won all the gold medals. Perhaps because of the aversions that he had created among the rancid Punic aristocracy, perhaps because of the limited resources of the treasury, the fact is that Xanthippus neither received what was agreed nor could he remain in Carthage after achieving his overwhelming victory over the Romans. He had instructed a formidable army of Punics and mercenaries, giving each unit its category and mission in battle and creating a military school that another Carthaginian genius would take to the highest places of strategy a few years later, but the Spartan was not one of them. , he was not a son of Melqart:he was a vile mercenary.

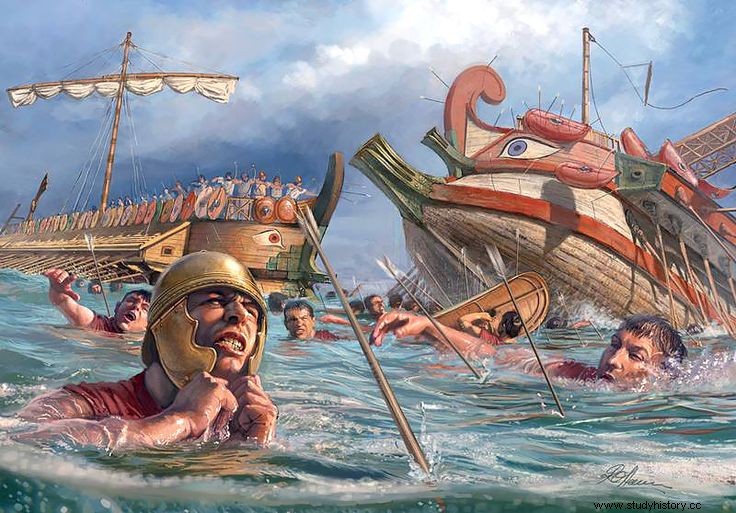

It is not clear what was the end of Xanthippus. Diodorus Siculus wrote that when he fled from Carthage he passed in front of Lylibaeum (today Marsala, in Sicily), at that time besieged by the Romans, and that thanks to his help the defenders were able to break the blockade, but that again, out of envy, the Punics boycotted his ship, drilling holes in it and it sank in the Ionian back home. The fact is that it is also known of a certain Xanthippus who only ten years later served as governor for the bellicose Ptolemy III Euergetes , the Hellenistic king of Egypt, so perhaps he could be the same individual.

Regulus returns to Carthage

What we do know is the tragic end of Regulus. He five years he remained in Carthage as a captive until, after the defeat of Panormus (today Palermo), the Council sent ambassadors to Rome to negotiate peace. Regulus was in said legation. It is said that the Roman at first refused to enter the city as a slave to the Punics until they convinced him to speak in the Senate, a chamber to which he said he no longer belonged after five years of absence. In the end, Regulus agreed to speak to the Senate, but not to mediate an armistice between the two cities, but to order his compatriots to fight to the end. Seeing them hesitant, he went so far as to tell them that he had ingested a slow poison that would kill him anyway, so they need not be moved by him, for he would be glad to return to Carthage as a prisoner bearing the Senate's resounding refusal of the peace treaty.

The Council of Carthage did not take Regulus' defiance at all well. He was sentenced to death, suffering the worst torture. One of them was to cut off his eyelids, leaving him for days in an underground cell and suddenly taking him out to the patio so that the scorching summer sun would burn his retinas. There was also a rumor that he was kept in a chest with iron spikes until he died. The Senate, horrified to learn of such an ignominious end, handed over the Punic hostages Bostar and Hamilcar to the consul's family, and it seems that they suffered a similar fate. Since then, Marcus Atilio Régulo he was placed in Rome as a symbol of heroism and sacrifice for the country. In my opinion, all of the latter must be taken with a grain of salt, since Polybius, our main historical source for this period and a generous man in detail, did not mention any of these torments in his writings, so this cruel ordeal could well have been part of the anti-Punic propaganda that had been forged against what was then "great archenemy of Rome".

Martyrdom of Regulus

To read good historical fiction about this era in general, and about this man as extraordinary as he was ignored by history in particular, I recommend The Eagle and the Lambda by the Cantabrian author Pedro Enrique Santamaría.