Intro

Between the 10th and 12th centuries, a mysterious "heresy" appeared in the South of France. Soon its expansion and its threat are such that the Catholic Church is forced to lead a war to eradicate this religion. Two crusades will be led by the kingdom of France, it is especially for the king of France to dominate all of Languedoc and Aquitaine. The fight against the Cathars will end with the fall of the fortress of Montségur in 1244.

The context

Occitan civilization

In the 12th century, the south-west of France was a very different region from that of the north of the Loire. A distinct language is spoken there (langue d'oc and not d'oïl) and a brilliant and refined civilization flourishes there. Moving from castle to castle, the troubadours, poets and musicians, sing of love, but also of honor and the negation of the right of the strongest. These ideas and values are very present in a region where educated people, especially in the cities, have kept the memories of Roman civilization alive. Rules, laws and codes limit the power of the great and govern the relationships that unite them to their vassals and their subjects. While in the Ile de France, the king fought on horseback and imposed himself in various ways on his recalcitrant vassals, in the towns of the Midi Languedoc and Aquitaine, the inhabitants elected consuls or capitouls who governed and spoke as equals. on an equal footing with the lords on whom they depend. Freer, the cities of the South are also the most welcoming to foreign ideas:their significant commercial activity (Toulouse is the third largest city in Europe) puts them in contact with many countries. The merchants who exchange foodstuffs and goods there draw ideas which they then spread to Occitania.

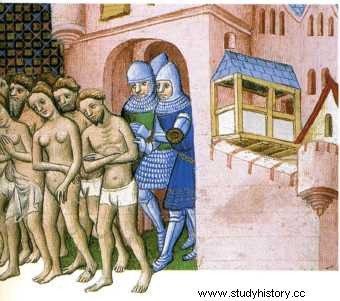

The Cathars expelled from the city of Carcassonne

(Illumination from the Grandes Chroniques de France. British Library, London. Photo D.R.)

The origin of the Cathar religion

It was in this milieu that a new religion spread, the success of which was so rapid that it frightened the Catholic Church. The latter was partly responsible for this extraordinary development:criticized from all sides and unable to reform itself, it prepared the ground on which Catharism could take root. Long before the appearance of the Cathar religion, many monks had preached open revolt against the Church, its priests and its sacraments:the requirement between greater simplicity in the relationship of men with God, a return to a faith less prisoner of the luxurious framework in which the Church had locked it up, were very widespread demands at the time. But Catharism was much more than a movement of simple criticism; it was also and above all a religion different from Roman Catholicism. The tradition that nourished it was very old since it had developed from the 7th century BC, around an important character from Antiquity, the Persian prophet Zoroaster. The latter thought that there existed in the universe two irreducible principles, Good and Evil, in permanent struggle against each other. The ideas of Zoroaster had a considerable influence throughout antiquity and they were broadly taken up in the third century AD by the prophet Manes, founder of the Manichaean doctrine. In the 10th century, in Bulgaria, this doctrine gave rise to the bogomiles (De Bogomile, the founder of the sect), who had taken up the religious ideas of the Manichean conceptions. Subsequently, a link of filiation was often established between Catharism and Bogomilism, however, this link is disputed today. If these two doctrines are very close, it seems that Catharism comes directly from Christianity and the Marcionist (from Marcion) and Gnostic doctrines. Catharism is indeed the fruit of scriptural work, proposing a different interpretation of the Gospels, in particular rejecting all the sacraments of the Catholic Church (water baptism, Eucharist, marriage, etc.).

The rise of the Cathar religion

The Cathar religion takes its name from the Greek term catharos, which means pure, because it gives man the goal of achieving perfect purity of soul. During the duration of his earthly life, considered as a test, Man must strive, by appropriate conduct, to break with matter, the physical world and gross needs. For the Cathars, who are also called Albigensians (from the Albi region), all this represents Evil to which Good is opposed, that is to say the purified soul, ignoring the desires of the body. Those who manage to purify their soul rest forever in the Good after death. The others must reincarnate indefinitely. For the Cathars, death was not feared because it could mean deliverance. This contempt for death gave them the necessary energy to fight the king of France and the pope. As early as 1147, monks were sent to restore reason to the Albigensians, but all failed. The last attempt was that of Saint Dominic (founder of the Dominican order), but he obtained only limited success. The pope gradually came to think that a holy war should be waged against them. The break between Cathars and Catholics was complete in 1208 when the papal legate was assassinated.

Believers and Perfects

The Cathars and those who were called "Perfect" or "Good men", who played the role of priests in a way, had to observe very strict rules. They were compelled to fast frequently, and a series of foods were forbidden to them in ordinary times. They didn't build temples, they prayed and preached wherever the opportunity arose. They rejected all the sacraments except the Consolamentum. It concerned believers wishing to become Perfect (a kind of baptism). The believer undertook to respect the rules specific to the Perfect:no more lying, no swearing, no more having sexual relations, very strict diet... Receiving the hug of his initiators, who then knelt in front of him, the new Perfect was supposed to feel the Holy Spirit descending on him. As long as they could freely display their opinions, the Cathars preferably dressed in black. After the crackdown, they were content to hide a black belt under their ordinary clothes.

Bernard Délicieux, the agitator of Languedoc (unknown, 19th century)

The fight against the Cathars

The first crusade against the Albigensians (1209 - 1218)

The assassination of his legate led the pope to raise a crusade against heretics. The King of France, Philippe Auguste, answered the call and left his most powerful vassals, the Duke of Burgundy, the Counts of Montfort and Saint-Pol to lead the army. 300,000 Crusaders descended on the Rhone Valley. The Count of Toulouse, Raymond VI, suspected of having encouraged the murder of the legate, had rallied to the Church and crossed paths against his own subjects. The Crusader army laid siege to the heavily fortified city of Béziers. However, the inhabitants, strong in this feeling of security, attacked the camps which stood at the foot of the walls. The rogues (mercenaries and knights recruited for the expedition) took advantage that the gates of the ramparts were open to make their way inside the city and then bring in part of the army. To the soldiers who wondered how to distinguish, among the population, those who were heretics from those who were faithful, the abbot of Cîteaux, Arnaud Amaury, replied with this terrible sentence:"Kill them all, God will recognize his! » The burning of Languedoc began:the city was set on fire and its inhabitants massacred. After Béziers, it was the turn of Carcassonne where the army announced itself at the end of July 1209. The soul of the resistance of the city was the young viscount Roger de Trencavel. The siege lasted three weeks, the besiegers had deprived the city of water, forcing the besieged to negotiate. Trencavel who had come to parley was taken prisoner by the crusaders, thus breaking the code of honor of chivalry. Simon de Montfort, a Crusader knight whose courage had been noticed, was chosen to succeed to Trencavel's estate. However, his subjects were understandably hostile to him. Also, until his death in 1218, he was constantly at war with his recalcitrant subjects.

Simon de Montfort, winner and loser

At the end of these long and trying sieges, the victorious Crusaders offered the life of the heretics who agreed to renounce their faith, but they were very few in number. By iron, fire and blood, the crusade continued, but the stake became clearer each day, it was a question for the lords of the North of mastering the South. The Count of Toulouse and the King of Aragon grew concerned about this, and in 1213 they joined forces to attack Simon de Montfort at the Château de Muret. The attack was cut short despite the numerical advantage, Pierre d'Aragon was killed, and Raymond VI had to retreat to his city of Toulouse, which was later invested by the army of Simon de Montfort. But the people kept a deep fidelity and preferred to go to the stake singing rather than denying their faith. When Raymond VI and his son Raymond VII returned from England where they had taken refuge, they were welcomed with great enthusiasm. A popular riot had driven the French knights from the city of Toulouse. At this news, Montfort immediately rushed to lay siege to the city, it was there that he was killed in 1218. His death was greeted with cries of joy:the Cathars saw the most cruel of their enemies disappear.

Simon de Montfort

Leader of the crusade against the Albigensians, he waged this war with courage and cruelty. He had already distinguished himself for his bravery during the fourth crusade. He represents the "puritanism of the north". He is the perfect opposite of his enemy, Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, symbol of the "libertine southern". They are the model of the clash of the two cultures involved.

The second crusade against the Albigensians (1226)

In 1224, new threats became clearer on the Occitan country. The new King Louis VIII will be even more implacable than his father Philippe Auguste. In 1226, when the lords and counts of the South saw themselves reinstalled on their lands, a second Crusader army was about to break into Languedoc, with the King of France in person at its head. Most cities collapsed or surrendered quite easily. Only Avignon put up a bitter resistance for three months. The death of Louis VIII saved Toulouse from a new siege, but the successive surrenders of his vassals ended up convincing Raymond VII that it was better to capitulate. By the Treaty of Meaux, signed in 1229, the Count of Toulouse pledged to remain faithful to the King and to the Catholic Church, to wage an intractable war against heretics and to marry his only daughter to the brother of the new King of France. , Louis IX, in order to prepare the annexation of Languedoc to France. After the signing of the treaty and the return of Raymond VII to Toulouse, the court of Inquisition was created and entrusted to a handful of Dominicans. Enjoying unlimited power, the inquisitors criss-crossed the South to flush out heretics. But these measures were not enough to stifle the aspiration of the South to believe and to govern as it saw fit. A second revolt shook the region after the assassination, in 1242, of the judges of the court of the Inquisition by Cathar knights.

Battle of Muret

The battle of Muret, September 12, 1213 was a turning point in the fight for the Occitan South, to the advantage of the royal army.

(National Library of France)

The capture of the castle of Montségur

A definitive peace was signed in Lorris in 1243 between the King of France and the Count of Toulouse. It was the end of independent Occitania and especially of Catharism. To deliver the coup de grace, however, it was necessary to take the fortress of Montségur, symbol of the refusal of royal authority, where 400 believers of the Cathar religion had taken refuge. The position of the fortress (a peak towering more than a hundred meters from the neighboring lands) gave a feeling of immense confidence to the besieged. For a year, they successfully challenged the authority of the king and the pope. The 10,000 soldiers engaged in the siege could only see the ineffectiveness of the cannonballs that were catapulted from the stones against the ramparts. However, one night in July 1244, thanks to the reinforcement of a group of mountaineers accustomed to climbing and knowing the area perfectly, the besiegers succeeded in entering the place by surprise and managed to obtain its complete capitulation. No longer having any safe refuge, pursued by the inquisitors, the last Cathars lived like hunted animals, sometimes causing brief revolts. The surviving Perfects emigrated to Catalonia, Sicily and Lombardy. Thus disappeared the most refined culture of the time:the Occitan civilization resulting from the myth of chivalry, chivalrous honor and courtly love, honored by the troubadours.

Montségur, an impregnable fortress

Montsegur was not a castle like the others. The architects who built it had the concern to build an easily defensible building. But they also had the will to build a true temple of the Cathar religion. Thus, the orientation of the building was not simply due to chance:its main axes were located in the alignment of the points which indicated on the horizon the places where the sun rises and sets at certain times of the year. year (equinoxes and solstices). The Sun held an important role as a symbol of Light and Good in the Cathar religion. Montségur has today become a symbol of the Occitan renaissance.

The treasure of the Cathars

After the fall of Montségur, many Cathars emigrated to Italy. That's where they probably transferred their treasure. It may be the old Visigoth treasure of Alaric, hidden in the vicinity of Carcassonne. However, at the beginning of the 20th century, near Rennes-le-Château, Abbé Béranger Saunière made exuberant expenses without anyone knowing where his fortune came from. One thing is certain, this priest has found a treasure. Could it be the treasure of the Cathars? Let's not forget that during the siege of Montségur, a handful of the besieged fled from the castle to a mysterious destination.