Twenty-first installment of “Archienemies of Rome “. Collaboration of Gabriel Castelló.

Our new archenemy is a complete unknown, but his undeniable military ability led to one of the greatest military disasters of the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC. One of the consequences of the Battle of Carrhae it was the acceleration of the end of the Republic, as well as the germ of a legend as immortal as that battle:The Lost Legion .

Surena is supposed to was born about 82 B.C. within the House of Suren , one of the most influential aristocratic families of the former Parthian Empire. Surena is the Greco-Latin version of the original Sûren, which was a fairly common name in its time and environment, even in present-day Armenia, since in Parthian it means "the hero". Marcellin indicated that, in addition to a name, it could also be a hereditary title:“The highest dignity in the Kingdom, next to the Crown, was that of Surena, or Great Commander, and this position was hereditary in a family in particular ”.

Surena

Whether it was his real name or just an honorary title, Surena was an extraordinary man. This is how Plutarch described it to us in his “Life of Crassus ”:

“Surena was a very distinguished man. In wealth, birth, and honor paid to him, he ranked next to the king, in valor and ability he was the greatest birth of his time, and in stature and personal beauty he had no equal.">

"...he was the tallest and the best man, but the delicacy of his gestures and effeminacy of his dress did not promise manhood as much as he actually had, or his painted face, and his hair parted in the manner of the Medes"

As an additional detail to enlarge his person, the historian tells us that Surena had a huge number of slaves enrolled in his personal army that were maintained by his own means. Other sources make the House of Sûren lords of Sakastan , between Arachosia and Drangiana, today the southwest of Afghanistan, being the parents of him Arakhsh and Massis.

His appearance in history took place at the siege of Seleucia from the Tigris , dated 54 BC, where Surena acted as lieutenant of King Orodes II in his family confrontation with Mithridates III, the king's brother and his political adversary. Wars and murders among Iranian royalty were common since the time of the Achaemenids, so it was completely normal to find kings who owed their throne to the death of parents or siblings. The geopolitical situation in the Middle East in those years was getting very complicated. Rome was controlled by a private pact that we know today as a triumvirate:Pompey, Caesar and Crassus they were the true owners of the Republic, each establishing an area of influence and enrichment. While Caesar was conquering Gaul and Pompey from Rome delegated his control of Hispania to Afranius and Petreius, Crassus, immensely rich but lacking the military talent of his partners, decided that his glory would be in the East.

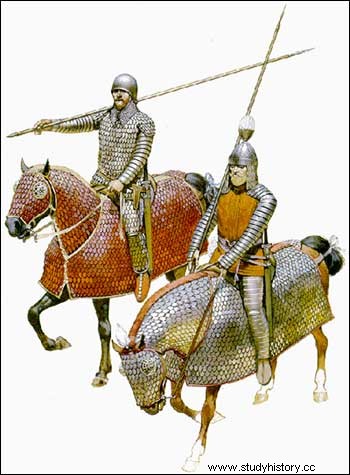

In 53 BC, Marcus Licinius Crassus Acting as governor of Syria, he commanded a spectacular army of seven legions, plus 5,000 Gallic horsemen and 5,000 auxiliaries, a total of 44,000 men. It may be that this desire for glory came from the poisonous advice of Ariamnes , an Arab who once helped Pompey, but was then in the pay of Orodes II of Parthia. Perhaps it was he who gave Crassus the notion of an easy victory when, in truth, he was sending the triumvir and his men to one of the most desolate spots in all the Middle East. His own son Publius accompanied him, willing to take the Syrian border beyond the Tigris and rejecting the military aid that Artavasdes , king of Armenia and ally of the republic, offered him in his Parthian campaign. Orodes II soon saw the danger that Crassus' thoughtless ambition could pose to his kingdom, but he was also aware of his ignorance of the ground he intended to conquer. Instead of mobilizing a large army to stop the Roman, he commissioned his faithful cavalry chief, Surena, to be the one to face the legions. King Orodes mobilized his army invading Armenia, while Surena set out to meet Crassus with 1,000 cataphracts (heavy cavalry) and 9,000 horsemen.

Cataphract

On June 9, 53 B.C. both armies met on the hot plain of Carrhae (today Harrán, in Turkey) Surena knew very well that she could not propose a pitched battle against Crassus, where Roman discipline and numerical superiority would be advantageous for her adversary, so she used to perfection the best qualities of her men:their mobility and effectiveness with the Parthian bow, much more effective than the Assyrian and whose curvature gave greater speed and power to the arrows, capable of crossing a hamata Roman (chain mail) at medium distance. They were able to shoot their arrows even in full flight...

This is how the Parthian horsemen began to harass the legions, even using camels to keep up the harassment while the mounts rested. This persistence forced Crassus to highlight his son from the main body of the army at the head of the Gallic cavalry, sending him to pursue an alleged Parthian withdrawal that turned out to be a cataphract charge that ended up enveloping the Roman troops in an immense dust storm until their extermination. The courage of the Gallic horsemen could do nothing against true knights covered in iron up to the eyebrows. The head of Publius Licinius Crassus He ended up on the top of a pole in full view of the legions.

Battle of Carrhae

Dismantled the Roman cavalry, Surena launched all his troops against the legions and Crassus's only relief was the arrival of night and the forced truce that this meant. The triumvir fell back on the city of Carrhae, leaving 4,000 wounded in the dust, which the Parthians finished off in their relentless pursuit. The following night, Crassus heeded the advice of a local guide who suggested a safe way back to Syria. His quaestor, Gaius Cassius Longinus , distrusted that guide and took 5,000 legionnaires and 500 horsemen out of there in the opposite direction and at his own risk. They were the only ones who could tell what happened. The next morning, the traitorous guide led the legions of Crassus to a difficult access terrain with no other way out than the army of Surena, who proposed a pact. With no water, no reinforcements, and no supplies, pressured by his men, Crassus agreed to parley. During that meeting, Marcus Licinius Crassus was executed, as well as the rest of the legates that accompanied him. After his death, Surena presumably ordered molten gold poured down his throat, in a symbolic gesture of mockery of Crassus's renowned greed. According to classical sources, such as Plutarch , 20,000 men were put to the sword in the dusty steppe of Carrhae and 10,000 ended up as prisoners of King Orodes II, giving rise to the fabulous legend of the lost legion . The seven eagles of the legions and the head of Crassus were sent to the king as macabre trophies.

The landslide victory of Surena it meant his immediate fall from grace before King Orodes, fearful of the power and influence that his subject had obtained thanks to such an extraordinary undertaking. The king, feeling threatened by Surena's possible betrayal, ordered his death in 52 BC. The Battle of Carrhae it did not produce a relevant border change (quaestor Cassius reorganized Syria and averted the following Parthian offensives) but it did break the balance of the Republic. With the death of Crassus, Pompey and Caesar were two roosters in the same pen. The bloody civil war that transformed the dying Republic into the Principality would take only four years to unleash.