When we see the term 'Machiavellian', manipulative rulers and ambitious politicians emerge. It is a word often associated with ruthless dictators of the 20th century:Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, Pol Pot; or the brain behind revolutions. Today, the British media also uses the term as a buzzword for the headline to create a sense of flair. They impose the word on influential advisers and ministers such as Dominic Cummings and Gavin Williamson, who took precedence over dubious means.

In psychology, Machiavellian individuals are interpersonally manipulative; they use flattery, deception and adopt cynical and amoral views against tradition to advance their own interests. Psychologists such as Wrightman suggest that people with Machiavellian characteristics have detachment. Because they lack an emotional connection with others.

Machiavelli misunderstood

It is clear that the term 'Machiavellian' has a deep negative connotation. But was the man himself - Niccolò Machiavelli, a manipulative individual flooded with greed and ambition? I do not think. Machiavelli was a Florentine philosopher and diplomat of the Renaissance. He served as secretary of the Second Chancery of Florence from 1498 to 1512, often involved in diplomatic matters. This experience in the real world sets him apart from early Western idealistic philosophers such as Plato, because he has a pragmatic view of politics. He was a writer and often studied history to use it as a guide to contemporary affairs.

Machiavelli's fame came from his dissertation - The Prince . This work challenges the Cicero's notion of virtue. He gave several historical examples of how bad men succeed and argued that given intention and telos are beneficial, an immoral means to an end can be forgiven. Machiavelli also gave many other controversial arguments. For example, in Chapter 5, Machiavelli suggests that after a prince conquers a republic, he should destroy existing institutions and dissidents, because Republicans never forget their freedoms and desire revenge. Consequently, researchers like Bertrand Russell called the dissertation "a handbook for gangsters", and Leo Strauss called Machiavelli a "teacher of evil".

In fact, without understanding the context of The Prince was written, and without reading Machiavelli's other works (which give very different views), it is easy to generalize Machiavelli as an evil thinker regarding the extraordinary arguments in The Prince . Scientists in the early 1920s, such as Strauss, did not get a complete picture of Machiavelli because it was not available. But with the discovery of several primary sources, a clearer picture of Machiavelli emerges.

Machiavelli's life

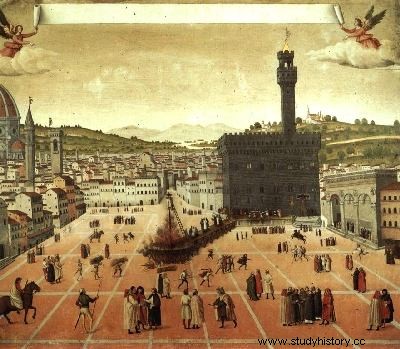

In fact, Machiavelli was a Republican and a Democrat in his political life. Democrat not by current criteria, but by Florentine standards. He was born in 1469 and was a student of the prestigious Latin teacher Paolo da Ronciglione. In 1494, the inhabitants of Florence expelled Medici, an influential family of bankers who ruled the city as a hereditary principal for over 60 years. During the decade, Machiavelli thrived under the protection of the Florentine gonfalonier (or chief administrator of life) Piero Soderini. He served as Secretary of Defense until 1512. Machiavelli worked for the interests of the republic. He participated in many major diplomatic missions, such as establishing friendship with King Louis XII of France and the Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian I.

Get out of politics

In 1512, medics received support from the pope. They defeated Florence's army and disbanded the Republican government. Machiavelli fell victim to political unrest. The drugs originally placed him in exile. Then they (wrongly) suspected Machiavelli of conspiracy in 1513; the man was imprisoned and tortured for several weeks. After his release, Machiavelli retires to his farm outside Florence. This gave him the opportunity to turn to literary pursuits.

Machiavelli wrote The Prince early in 1514. The work is a dedication to Lorenzo de'Medici. Machiavelli opens the dissertation with a letter of dedication, in which he connotes, the purpose of the work is to show the medicines how they can scale greatness and bring honor to their large family. Machiavelli also suggests, by advising the Medicines, that he wants to win their favor. In fact, many of Machiavelli's former colleagues in the Republican government were rehabilitated and served Medici. As Cary J Nederman claims, Machiavelli composed The Prince in great haste; he sought to regain his status in Florentine political affairs. Of course, we can not read Machiavelli's mind and find out the true motivation behind this composition. Oxford sociologist Stein Ringen explains:

"Maybe he wanted to flatter the young prince to get a job ... Maybe his intention was not useful advice at all, but rather to confuse the autocrat with counterproductive ideas and thus entice him to fail. Machiavelli was defiant. all a man of the republic who had every reason to dislike the new regime.or maybe not.Although he was a man of the republic, he was also desperate for work and position, and needed income, and probably very ready to go on agreement with his principles if he could get back into public service. "

Machiavelli the Republican

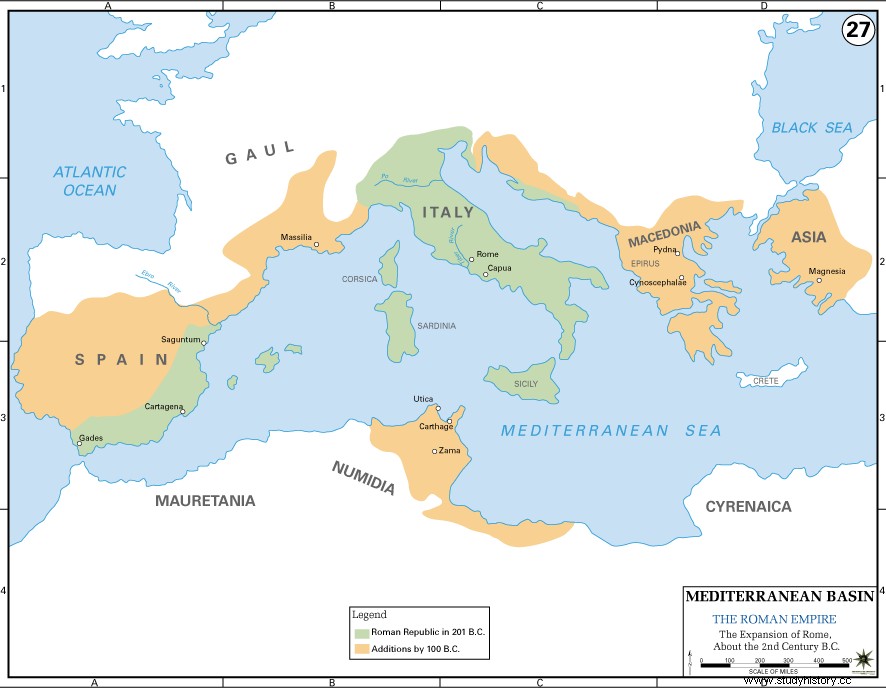

Still, like The Prince The content seems to be inconsistent with Machiavelli's Republican upbringing and his other works, and since Machiavelli has a personal agenda at the time of writing, I do not think that the dissertation fully reflects Machiavelli's true beliefs. Machiavelli's other great works - The Discourses of Livy , completed in 1519, offers a completely different conception of art to rule. In this work, Machiavelli's thinking is more noble and traditional. He explores the Roman Republic:how novels founded and maintain this form of government, and more importantly, how Roman wisdom in political art can be used by all republics. Here Machiavelli is democratic (by Florentine standards). He suggests that republics are better than principalities.

The republic exists for the benefit of the people instead of elevating a leader. For another, decisions made by the republics take their form from debates among the citizens and between the people and their leaders. This process results in better decisions than the whim of an autocrat. The empowerment of the people stands in contrast to the ruthless dictatorial tactics advocated by Machiavelli in The Prince .

So, we should just reject The Prince as a dishonest job application? No. For although Machiavelli wrote that dissertation with a clear agenda, the argument in The Prince is also supported by extensive historical examples and logical reasoning, suggesting solid empirical evidence.

Therefore, Machiavelli was a thinker who could be both idealistic and realistic. He can stand in the shoes of either an expansionist prince or a traditional Republican, as he took on board different perspectives in different works. The rest of this article provides an introduction to Machiavelli's thoughts in The Prince and The Discourses on Livy.

The Prince - A guide to effective governance in a rectorate

realpolitik

The principle of "goals justify the means" is a recurring theme in this dissertation. Some of the tools Machiavelli proposed are extreme. In Chapter 3, Machiavelli discusses a principal's expansion. When he conquers another feudal rectorate, the prince should eliminate the family of his former masters. As for the crime that someone in the annexed state can take to a new ruler, he suggests that the only way to maintain peace is to make the prospect of a successful uprising seem impossible:

"Men should either be treated well or crushed, because they can take revenge on minor injuries, on more serious injuries they can not; therefore, the harm to be inflicted on a man should be of such a nature that one is not in fear of revenge. "

This is political realism; Machiavelli prefers action to moral persuasion. Some atrocities are committed better than others. In Chapter 8, he explores the difference between properly and poorly used atrocities in the form of mass executions. Machiavelli suggests that when a conqueror takes power, he must decide on all the damage he needs to do and do it all at once. That is, committing brutality in a short period of time is relatively better than suppressing the masses slowly, as the people will remember and dislike the latter. Never before in the Western political tradition of thought has a philosopher put forward such a bold argument. Neither did Plato, nor did Cicero.

Power and fraud

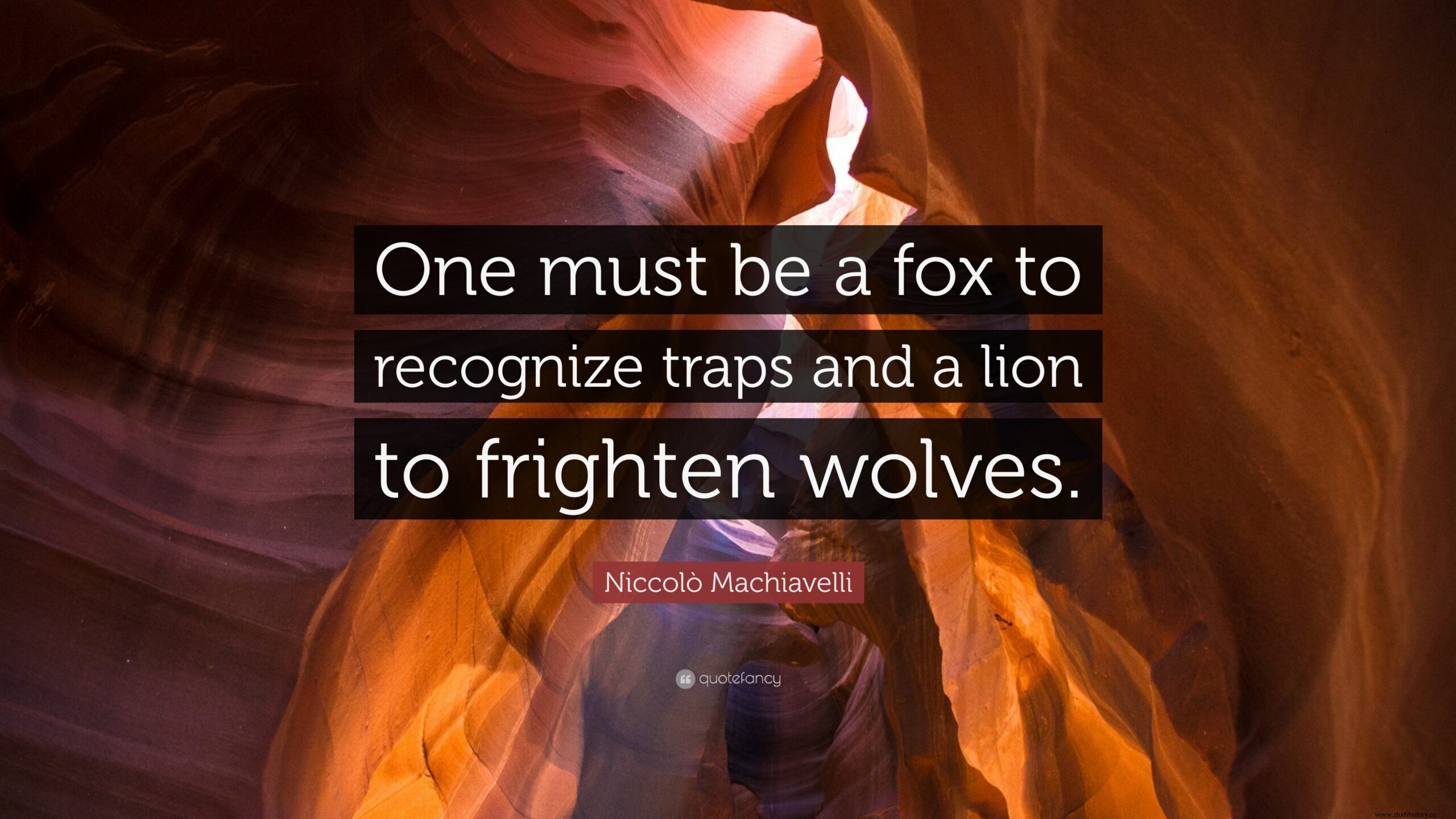

In fact, Machiavelli examined the ideas put forward by early Republican philosophers and reversed them. Hos Cicero De Officiis , who guides honorable political life and republican virtues for young patricians, he invented the lion and fox parable. Cicero suggests that both the lion and the fox are beastly, and a leader should never imitate the qualities the two beasts embody, namely the violent use of force and deception. Machiavelli rejects this view, arguing that a prince must learn to be an animal and use force. He should also know what special animals to imitate at the right time. "Those who have done best as princes of our time have been able to imitate the lion and the fox," Machiavelli writes. Therefore, a successful prince must be both powerful and cunning.

Reputation and reality

Maintaining a respectable image involves such cunning. The people must look at the prince as an embodiment of generosity. But the prince should never exercise generosity in a conventional way. If generosity is exercised in the way it really should be, like humbly doing good without boasting, it will go unnoticed. Traditionally, rulers organize lavish parties to develop a generous public image. This is wrong, costly and financially unsustainable. In the long run, this will lead to a depletion of resources and excessive taxes. Consequently, the ruler loses popular support. Therefore, a prince who wants to have the reputation of generosity must be rude over some small acts of kindness to make it known.

Glory

Yet the Prince's philosophies are not without morals. Machiavelli argues that a prince should aim for glory as the ultimate goal, which surpasses the importance of power. While evil means can help a prince cement power, a prince cannot gain glory through pure evil. A truly magnificent prince can not be devoid of conscience. Here Machiavelli uses the example of Agathocles from Syracuse to convey the point.

Agathokles was of low birth. But through his wit, fighting skills and great energy, he became a military commander. He invited the Senate and leading citizens to a meeting to become the ruler, where he massacred them. With obstacles out of the way, Agathocles transformed into the king of Sicily. Machiavelli claims that criminal acts gave Agathocle power, but they cannot place him among the really great rulers in history, whose actions are to be admired and imitated.

There are great nuances in Machiavelli's arguments. While acknowledging the importance of political realism and the need to use immoral means to gain power, he also suggests that a prince should exercise restraint in how much cruelty he is willing to commit. A glorious prince needs to find a balance; he is a man of conscience and moderation, instead of a tyrant with ambition.

The Discourses - Republican stability

Machiavelli here is very different. As intellectual historian James Muldoon puts it, 'Imagine your friend telling you about some awful coworker at work, but when you meet them, they're actually pretty nice.' In this work, Machiavelli commented on the first ten books of Livy's Rome History . He analyzes the success behind the Roman Republic and advocates this form of government as superior to all.

Benefits of Class Conflict

Why was the Roman Republic so lasting? Machiavelli's response is that sporadic riots and party political conflicts helped Rome maintain long-term peace. The Roman bourgeoisie (plebeians) make up most of the army. They choose to represent their interests in the Senate; the senate body consists mainly of patricians (nobles). Of course, patricians pass the laws, because they have wealth and influence. Machiavelli values the nobility low and suggests that they have a desire to dominate:

"Without a doubt, if we take into account the goals of the nobility and ordinary people, we will see in the first a strong desire to dominate and in the latter only the desire not to be dominated." (Chapter 5, Book 1, Discourses)

Machiavelli on the other hand, had a terrible day. He argues that the wishes of free people are seldom detrimental to freedom, because they arise either from oppression or from suspicion that they will be oppressed. Therefore, the republican empowerment of the plebeians is crucial. They have stands to express their concern; they have arms, which means protests can be disruptive. Or they may withdraw from the city to make the nobility vulnerable to external attacks. The empowerment of the people fundamentally prevents the patricians from establishing an oligarchy that serves their interests exclusively. While educated patricians should demand true virtue as the people reverence, and make policies that are fair to the masses and beneficial to the republic. The Roman Republic therefore reached a class balance of mutual fear and respect.

Diplomacy and expansionism

As a rare continuity from The Prince , Machiavelli and the Discourses also advises fox-like cunning in the sphere of diplomacy. Machiavelli suggests, the best method of expansion is to enter into alliances with friendly neighboring states, given the condition that your state retains the leadership position. They conquer together, and reduce kings to provinces. The Allies would receive decent portions of the booty in favor of the state. Nevertheless, since Rome has the title of command, Roman officials ruled conquered states, so the ultimate political control over conquered territories belongs to Rome.

Therefore, Roman allies found themselves in a stoke surrounded by novels. With this process, Rome's military workforce grew through the acceptance of immigrants into the army. When the Allies notice this deception, they have no means to turn the tables due to Rome's pure skill after expansion. This is another glimpse of Machiavelli's political realism - a state should use its allies to achieve its political agenda.

The big reset

Despite class equilibrium and diplomatic successes, the republic will inevitably be corrupted over time. Expansion sometimes leads to corruption. Expansion needs professional armies and generals; the latter are charismatic populists who could easily get the soldiers to serve them instead of the republic. This is how Sulla and Caesar become destroyers of the republic. Machiavelli suggests that in order to counteract these demagogues, a republic needs a famous statesman with exceptional strength and ability to return it to its basic principles, such as the rule of law, the empowerment of the masses. The citizens of the Roman Republic were repeatedly able to choose such leaders to help them find their way back from decay. Rome's record of success is remarkable, lasting more than 400 years.

Final remarks

Niccolò Machiavelli's philosophy is multifaceted. This article challenged the popular notion of Machiavelli as a manipulative planner and emptiness of morality. It has attempted to provide an overview of his life and some fascinating themes in two of his major works, namely The Prince and the Discourses . When we read political philosophy, it is far too easy to judge a thinker by our contemporary values. We can also accept the mainstream critique of a thinker. This is wrong. Previous writers could not have supported ideas today because they had been inaccessible in the authors' context. Nor did they want to know how their ideas were articulated in history. In fact, we can not take hindsight for granted and prosecute previous authors for others' misuse of their ideas.

Readers should perhaps take a contextualist approach, namely to understand the political and intellectual context in which a philosopher wrote. This not only ensures historical integrity, but also opens up new frameworks of analysis. In this way, we would not bash Machiavelli from the hypocritical moral heights, but sympathize with an intellectual in a turbulent time of political paradoxes.