Martin Luther King Jr. we do not remember

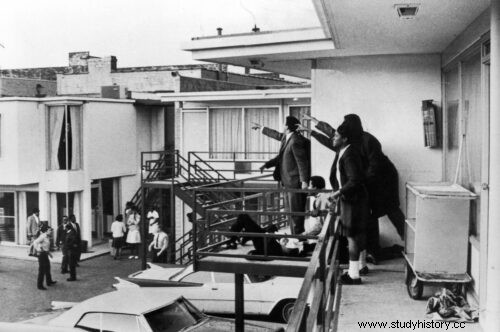

History today remembers Martin Luther King Jr. like this benevolent, saint-like figure. He is best remembered for his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech delivered in front of the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963, in which he shared his dreams of an America no longer stained with racism, segregation and inequality. The king's policy in development in the last years of his life, by comparison, is not so much remembered. King was strongly critical of the American capitalist system. He believed that capitalism "has often left a gap between superfluous wealth and terrible poverty, created conditions that make many people have to take necessities to give luxury to the few, and has encouraged small-hearted men to become cold and unscrupulous" (King Jr. ., 2010, p. 197). King was also strongly opposed to the Vietnam War and stated in his 1967 speech "Beyond Vietnam:A Time to Break Silence" that it was a moral, political and economic disaster that destroyed President Lyndon B. Johnson's programs for the war on poverty (Freeman &Kolozi, 2018, p.7). Chances are high that a quote by King will be posted and shared on social media today, it will not be a quote that reflects his views on capitalism or the Vietnam War. If we as Americans really want to honor King and his legacy, we must recognize him for the daring and radical person he really was. There is no better way to do that than to reflect on the Poor People's campaign, an effort he organized and led to the assassination on April 4, 1968.

Shift focus

King was deeply disturbed by poverty in the United States, especially when he experienced it on his own (Messman, 2007, p. 30). He moved the family to a residential unit in Chicago's Lawndale slums between 1965 and 1966 (Messman, 2007, p. 30). Terrified of the conditions in which the inhabitants lived, it was during this period that King wanted to expand the black struggle for freedom into a human rights struggle (Pearlman, 2014, p. 25). He confided in actor and activist Harry Belafonte that while he believed it was right to fight for integration, he was concerned that he should integrate his people "in a burning house" (Freeman &Kolozi, 2018, p. 14). There was still deep social, political and economic inequality in the United States despite the victories achieved from March 1963 in Washington (Pearlman, 2014, p. 27). King quickly realized that he had to shift his focus in the fight for equality against class (Freeman &Kolozi, 2018, p. 3). He felt that until the problems of poverty and economic inequality were properly addressed and resolved, anger and violence would continue to be perpetuated in the United States (Freeman &Kolozi, 2018, p. 14). In his book from 1967 Where do we go from here:Chaos or community ?, King wrote , "In short, the problem of Negroes cannot be solved unless the whole of American society takes a fresh look at greater economic justice," (King Jr., 2010, p. 51).

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

The idea for the Poverty Campaign was created during a five-day retreat held by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in November 1967, where Martin Luther King Jr. served as the first president (Pearlman, 2014, p. 26). SCLC was founded January 10-11, 1957, during a meeting convened by King, Charles Kenzie Steele, and Fred Shuttlesworth at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia (Fairclough, 1986, p. 423). They sent about 100 invitations to mostly South African ministers from the south, 60 of whom responded (Fairclough, 1986, p. 423). It was during this meeting that the participants agreed to establish a civil rights organization that would focus on promoting non-violence and abolishing segregation (Fairclough, 1986, p. 423). King's election as president of the organization was a foregone conclusion and met with no opposition due to his previous work in the Montgomery Bus Boycott 1955-1956 (Fairclough, 1986, p. 427). SCLC is a community mobilizing organization, which strongly believes in public confrontation as the most effective way to bring about radical change (Miller). The organization is still active today and is concerned with educating others about personal responsibility, leadership potential and community service, as well as fighting for social, economic and political justice through non-violence (SCLC, nd). Charles Steele Jr. currently serves as President (SCLC, nd).

A campaign for the poor

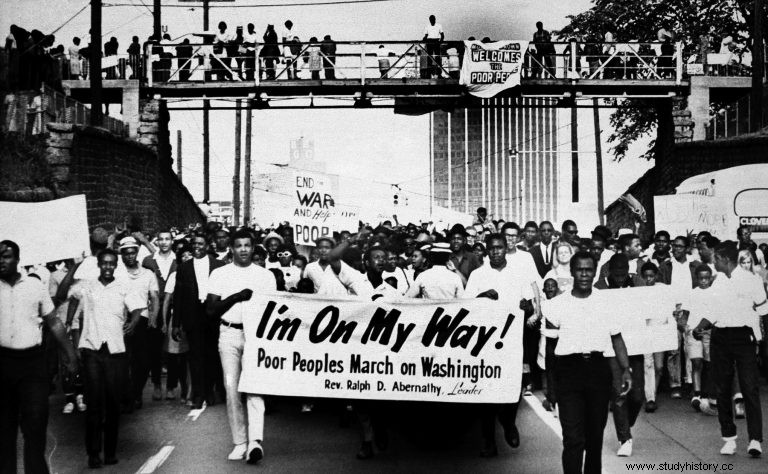

The Poor People's Campaign was designed by SCLC, led by King, to raise awareness of American poverty and its diversity, challenge the structural root of poverty, and achieve economic justice for the poor (Pearlman, 2014, p. 26). It was meant to resemble a "non-violent uprising, a multiracial coalition of poor people and their allies who would march to Washington, DC, create mass camps and then start protests every day for economic justice" (Messman, 2007, p. 30). . The SCLC targeted people of all backgrounds - whites, blacks, Indians, Mexicans - for their support and participation in the campaign (Beagle, 2000, p. 238). Their strategy was to give the federal government no choice but to adopt an economic declaration of rights that would guarantee affordable housing for all, a decent income for those who could not work, equal educational opportunities for the poor, a public work program for the inner city and more ( Messman, 2007, p. 30). This would be achieved through mass demonstrations, lobbying and training of poor people in the discipline of non-violence (Pearlman, 2014, p. 26). It would also be achieved through the creation of the Resurrection City, a mass camp of poor people in the National Mall (Messman, 2007, p. 31). Resurrection City would force the public to confront poverty and the struggle of poor people (Messman, 2007, p. 31). It is no coincidence that the campaign's main objectives, the Capitol Building and the White House, were functions of the most powerful government in the world (Messman, 2007, p. 31). King wanted the campaign to disrupt and paralyze prominent government buildings until the federal government took action to tackle poverty (Messman, 2007, p. 32).

Broken dreams

The path of the Poverty Campaign changed drastically when King was assassinated just a few weeks before it was launched (Beagle, 1968, p. 239). The management structure of SCLC was dominated by and built around King (Fairclough, 1986, p. 429). According to Baynard Rustin, a civil rights organizer and activist who was an integral part of the founding, "the structure of the SCLC was autocratic .... major decisions rest on Dr. King" (Fairclough, 1986, p. 430). The public image and appeal to SCLC was also framed around his personality (Fairclough, 1986, p. 430). Simply put, there was no Southern Christian Leadership Conference without Martin Luther King Jr. That is why his death was such a blow to the campaign. Ralph Abernathy succeeded him as SCLC President and Leader of the Poor People's Campaign (Freeman &Kolozi, 2018, p. 23) Peter S. Beagle, a writer who participated in and covered the campaign, heard a woman in Resurrection City say:“Dr. King could talk for twenty minutes, and I would not understand a single word he said, but it did not matter. Dr. Abernathy, he speaks for two hours, and I understand every word. But I suppose I do not care "(Beagle, 1968 , p. 253) King was such a charismatic leader, once in a lifetime one, whose shoes were impossible to fill.

Nowhere but to go down

The Poor People's Campaign was officially launched on May 12, 1968 in Washington DC, where Coretta Scott King led a protest demanding an economic law on rights (Freeman &Kolozi, 2018, p. 23). Everything looked good, but things quickly fell apart. The campaign management was disorganized and unfocused with King out of the picture (Freeman &Kolozi, 2018, p. 23). SCLC lacked serious resources. They could only build shelters for around 700 people in Resurrection City, forcing other participants in the campaign to find other places to live (Pearlman, 2014, p. 34). This housing shortage contributed to Resurrection City being disproportionately black, not multiracial as it was intended to be (Beagle, 1968, p. 247). SCLC had to hold a press conference afterwards and ask department heads for more than $ 3 million in additional funding (Pearlman, 2014, p. 34). There was also a shortage of food for all participants (Beagle, 1968, p. 245). They had to seek out and receive meals from local private organizations, church and synagogue groups, and the DC Health and Welfare Council (Pearlman, 2014, p. 34).

Worst of all, SCLC lost control of its campaign participants. Many participants began to act out and behave badly as the campaign continued (Pearlman, 1968, p. 34). There were many reports of rapes, robberies and attacks on tourists and journalists in Resurrection City (Beagle, 1968, p. 249). There was also violent drug and alcohol consumption among the participants (Beagle, 1968, p. 249). This violent behavior should prove to be the downfall of SCLC. On June 20, 1968, 300 participants in the Poverty Campaign were involved in an argument with a police officer near Resurrection City (Pearlman, 2014, p. 36). The conflict got worse when the policeman asked for a backup, with 150 officers coming to the scene (Pearlman, 2014, p. 36). Participants began throwing stones, bottles and batons at police officers, who responded with tear gas (Pearlman, 2014, p. 36). Three days later, some young people who made a mistake in being part of the campaign threw stones at police officers stationed outside Resurrection City. The Department of Justice concluded that SCLC's "failure to impose the appropriate sanctions for the June 20 uprising had created a general lack of discipline in the camp" (Pearlman, 2014, p. 36). National Park Service officials then denied SCLC a permit extension for Resurrection City (Pearlman, 2014, p. 36). Thus, the Poverty Campaign effectively ended on June 24, 1968

The legacy of the poor people's campaign

The poverty campaign was ultimately a failure because it failed to achieve what it set out to do. There is no economic law on rights. Poverty continues to exist, and it is estimated that nearly 41 million Americans are living in poverty right now (Booker, 2018). Worse, the campaign is largely forgotten today, especially in the context of the life of Martin Luther King Jr. However, the campaign achieved some gains. According to child rights activist Marian Wright Edelman, it was not a complete failure because it succeeded in getting the federal government to improve conditions for the poor (Desmond-Harris, 2017). She had a point. The campaign put pressure on Orville Freeman, the Secretary of Agriculture, to get the federal government to invest more heavily in food stamps (Beagle, 1968, p. 249). This resulted in the implementation of food distributions in around 250 poverty-stricken counties across the country (Beagle, 1968, p. 249). There were also large investments in nutrition programs and school lunches from the federal government as a result of the campaign (Desmond-Harris, 2017). Another success of the Poor People's Campaign was the attention it drew to American poverty (Desmond-Harris, 2017). SCLC President and Co-Founder Joseph Lowery argued that it made the country more aware of its growing impoverished population (Desmond-Harris, 2017). In the wake of the campaign, the reality of poverty could no longer be denied (Desmond-Harris, 2017).

Lost in the discussion surrounding the failure of the Poverty Campaign is how relevant its values and goals still are. It has been revitalized by Ministers William Barber II and Liz Theoharis (Booker, 2018). The new campaign, Poor People's Campaign:A National Call for a Moral Revival, is a continuation of King's legacy and his recent organizational efforts (Booker, 2018). In addition to poverty, the campaign also addresses systematic racism, the war economy and ecological destruction (Booker, 2018). Among the campaign's list of demands are increases in federal and state wages, reinvestment in public housing and redistribution of resources from the military budget to education, health care, jobs and green infrastructure needs (Booker, 2018). These are some of the problems the Poverty Campaign tackled over fifty years ago. "Injustice everywhere is a threat to justice everywhere," King wrote in the letter from Birmingham Prison, five years before the Poor People's Campaign. Economic injustice is really a threat to everyone's justice. The United States is characterized by economic injustice and will continue to be so, unless serious measures are taken to combat it.

References

Beagle, P. (2000). The poor campaign. Creative Nonfiction, (15), 236-259. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/44362945

Booker, B. (2018, May 14). The poverty campaign seeks to complete Martin Luther King's last dream. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2018/05/14/610836891/the-poor-peoples-campaign-seeks-to-complete-martin-luther-king-s-final-dream

Desmond-Harris, J. (2017, January 16). The Poor People's Campaign:the little-known protest MLK planned when he died. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/2017/1/16/14271074/poor-peoples-campaign-mlk-protest

Fairclough, A. (1986). The Preachers and the People:The Origins and Early Years of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1955-1959. Journal of Southern History, 52 (3), 403-440.

Freeman, J., &Kolozi, P. (2018). Martin Luther King, Jr. and America's Fourth Revolution:The Poor People's Campaign at Fifty. American Studies Journal , (64), 1--18.

King, ML, King, CS and Harding, V. (2010). Where do we go from here:Chaos or community? Boston:Beacon Press.

Messman, T. (2007). The Poverty Campaign:Nonviolent Rebellion for Economic Justice. Race, Poverty, and the Environment, 14 (1), 30-32. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41555132

Miller, M. (nd). Alinsky for the Left:The Politics of Community Organizing. Retrieved from https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/alinsky-for-the-left-the-politics-of-community-organizing

Pearlman, L. (2014). More than a march:The poor campaign in the district. Washington History, 26 (2), 24-41. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23937716

SCLC. (nd). Retrieved from https://nationalsclc.org/