What's the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word ' nationalism ? "Do you imagine a movement of people who, united with their distinct culture, language and interests, seek separation and political independence from the dominance of aliens?

What if I tell you that (especially when we talk about African nationalism) it is only a partial correct answer?

INTRODUCTION

The process of decolonization in Africa is usually portrayed as the victory of the nationalisms that were blacked out by elites, ie nationalism, which promoted the independence of existing colonies. In fact, nationalism is often defined as an anti-colonial ideology that envisions a nation as a political community that should rightly be independent of the rule of others. [1] However, this definition does not include other African nationalism , which is often overlooked by historians of African decolonization.

It is important to remember that nations are not European inventions since they existed long before European colonization of Africa, and continue to exist after decolonization. [2] Every nation, which consists of one ethnicity, can exist in a state and coexist with other ethnicities (or nations) without ambitions to achieve political independence.

In fact, most nations do not seek to challenge or renounce the legitimacy of the nation state, and the concept of ' ethnicity 'is really best reserved for the political communities without ambitions to achieve political independence. [3]

With this in mind, this blog will explain that since a nationalist is the one who fights for freedom and the one who, depending on his role in society, has his own understanding of what this freedom entails, national leaders who do not seek the creation of an independent nation-state, but who strive to achieve this freedom, whatever it entails, should also are considered nationalists.

I will analyze three Kenyan nationalisms during the 1950s loyal, moderate and radical nationalism - and would argue that it is wrong to think of nationalism as an ideology that only The goal is to achieve the nation's sovereignty / independence. Instead, when I read about African decolonization, I will try to encourage you to always think of an idea of competing nationalism , which involves a complicated struggle between ethnic and nation-as-state nationalism, for a broader understanding of African historical processes at that time.

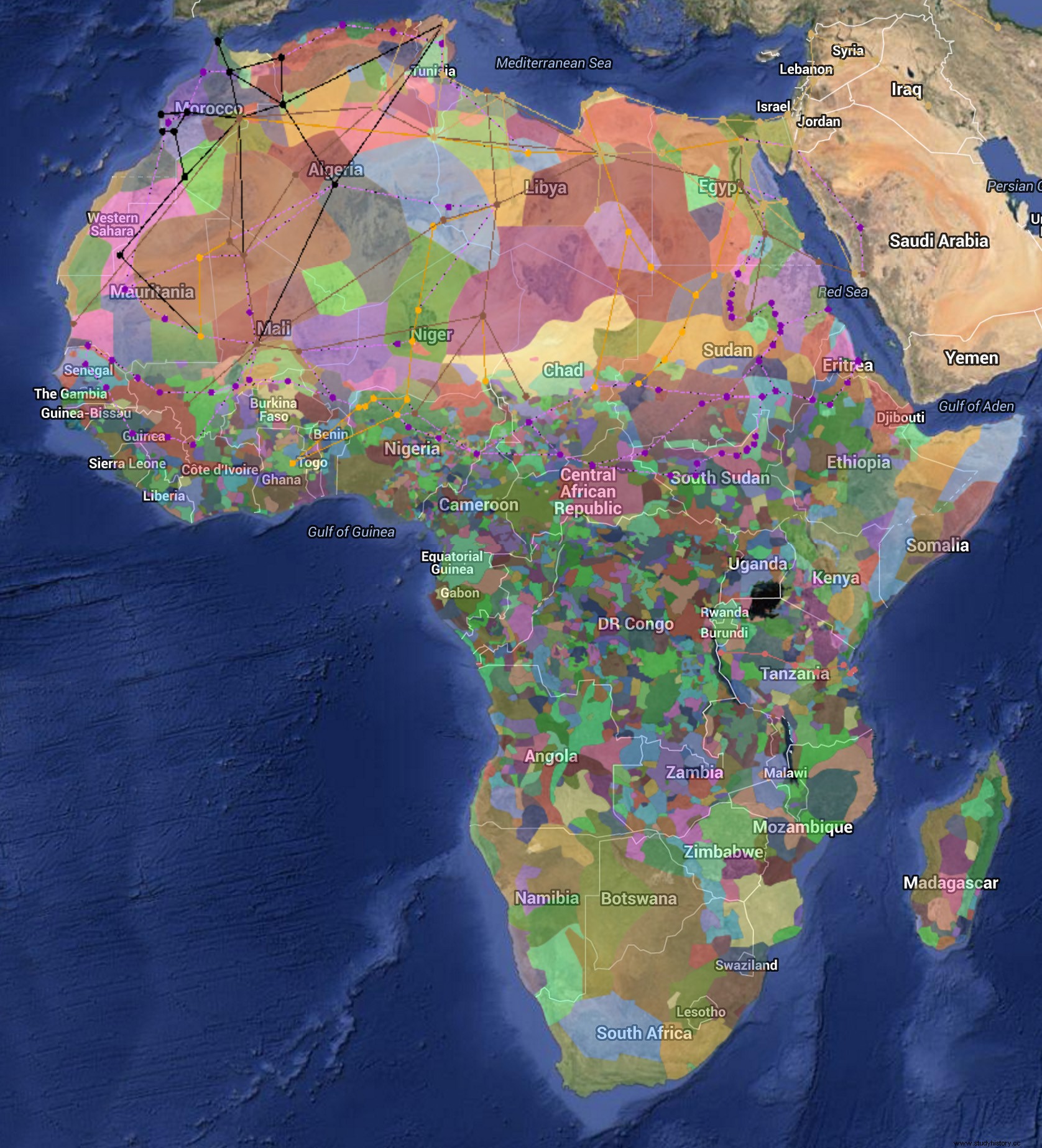

To illustrate my point, I will focus on the Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1960) , as one of the most violent events in Kenyan colonial history where several nationalisms collided. Since the uprising was dominated by the largest Kenyan ethnic group Kikuyu , throughout my blog, I will refer to them most.

However, before you dive too deep into the explanation of competing nationalism During the Mau Mau Uprising, it is important to understand some cultural aspects of the Kikuyu tribe.

KIKUYUS MORAL ETHNISITY

A Kenyan nationalist, like all other nationalists around the world, has always fought for freedom. [4]

The meaning of the word ' freedom 'is not transparent, however, as it depends on "what those who use it intend to achieve through use. "[5]

Will they achieve political independence? Or will they instead achieve an element or entity that would give them more freedom than any geographical separation would have been able to? Or both?

To understand the "type" of freedom and the reason why you achieve it, it is therefore important to understand the importance of moral ethnicity .

Moral Ethnicity is basically a code of conduct that guides the behavior of ethnic communities. [6] In other words, moral ethnicity is something that gives the tribes their meaning. [7]

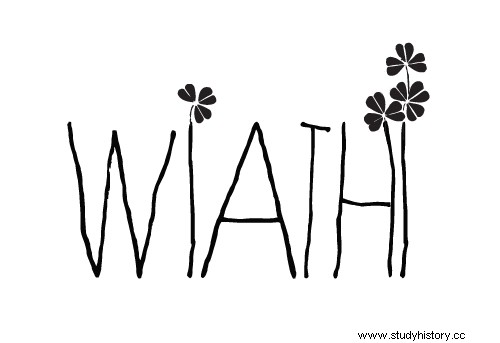

In Kikuyu culture, freedom is determined by one's ability to exercise authority and to make decisions in society. [8] This authority is embodied in wiathi , which is translated from Kikuyu as self-control, freedom and independence. [9]

Wiathi depends on two main ingredients :

- Possession of land

- Hard work [10]

Kikuyu believed that access to land not only determined a person's economic position, but also his reputation value:“without land one could not marry and set up a productive household, [and] without a productive household, one could not become the oldest in society. "[11] Being an elder meant being able to exercise authority in one's own moral community because of material self-sufficiency.

In addition, the amount of wealth also determined one's degree or wiathi or freedom:the richer the person was, the freer that person was supposed to be. [12] Therefore, Kikuyu had political elites who had the highest level of wiathi because of the wealth of the household, they have exercised a "monopoly on the wealthy". [13]

However, in addition to owning the country and being rich, the elite also had to legitimize their moral authority through their offer to the poor without land, access to land for them to "follow in their footsteps for self-mastery" [14], since freedom was also characterized by the ability to work hard.

Therefore, without land one was free since it was impossible to exercise authority by being materially dependent on others . [15]

FORLEV TIL MAU MAU-OPRÅBLINGEN (1952-1960)

The Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1960) was a Kenyan (Kikuyu-dominated) nationalist movement that originally aimed to expel British colonists only.

After World War II mechanization of farms led white farmers to begin to view Kikuyu squatters as unwanted burdens:

- by 1948, about one million Africans were displaced from the country to an area of 2,000 square kilometers, meanwhile 30,000 occupied 12,000 white XNUMX XNUMX square kilometers. [16]

- by 1953, half of Kikuyu lost rights to the land of his ancestors while poverty, unemployment, social and mental disorientation became widespread and caused disagreement. [17]

Therefore, the Mau Mau uprising became known as the 'land movement' - and that was when the Mau Mau rebels formed armed troops to challenge discrimination from the British Crown.

'LOYALIST' NATIONALISM

It should be pointed out that colonial rule was not the only one that was guilty of ethnic and economic discrimination against the Kikuyu people, since colonialism has always consisted of an alliance between rulers and rulers. [18]

It was believed by colonial officials that it was a universal and linear process of development from tribalism to modernity - that is, from tribes to universal modern secular societies.

Colonialism, which introduced European 'modernity' to Africa, was believed to ultimately stimulate "social change by driving people out of the old" tribal "ways of doing things and drawing them into larger social arenas." [19]

Hence, nationalism , which is believed to lead to a political independence of a secular nation-state, was thus seen as the inevitable end product of the impact of colonialism on African tribes . [20]

Colonial states began to regard themselves as the "engines of social transformation" [21] and thus employed paternalistic authoritarianism where the local black bourgeoisie would learn to govern in order to eventually gain access to govern their national institutions.

This 'creation of an African political class' by the colonial office was not altruistic, as it allowed Britain to withdraw its responsibility from financing and developing its colonies, while still controlling and indirectly conducting public affairs in its ex-colonies through blacks. elites who were taught to share the views of their colonial leaders. [22]

In fact, since nationalism was seen by the British government as an ultimate tool for a successful transition to neo-colonialism that the affiliation of the African masses to European values of sovereignty and independence could only logically be promoted by Western-educated black bourgeoisie ( athomi ). [23]

KAU

Members of the first anti-colonial Kikuyu-dominated pan-ethnic nationalist party , Kenya African Union (KAU) , established in 1944, has accepted the principles of the British version of modernization and nation-building. [24]

The athomi were educated in world history and the history of British violent repression of various armed insurgency at home, and thus believed that they could secure benefits for their communities only through constitutional legal means and peaceful negotiations with the colonial government.

Therefore, despite the conventional notion that all nationalist politicians are strong opponents of the colonial system and want to destroy it, this was not the case with many members of KAU who were 'inspired' by progressive Western nations and believed that it was only through European education one could achieve the progressive levels of Western 'civilizations' [25] in addition to the imperial recognition of Kenya as a nation state.

MODERATE NATIONALISM

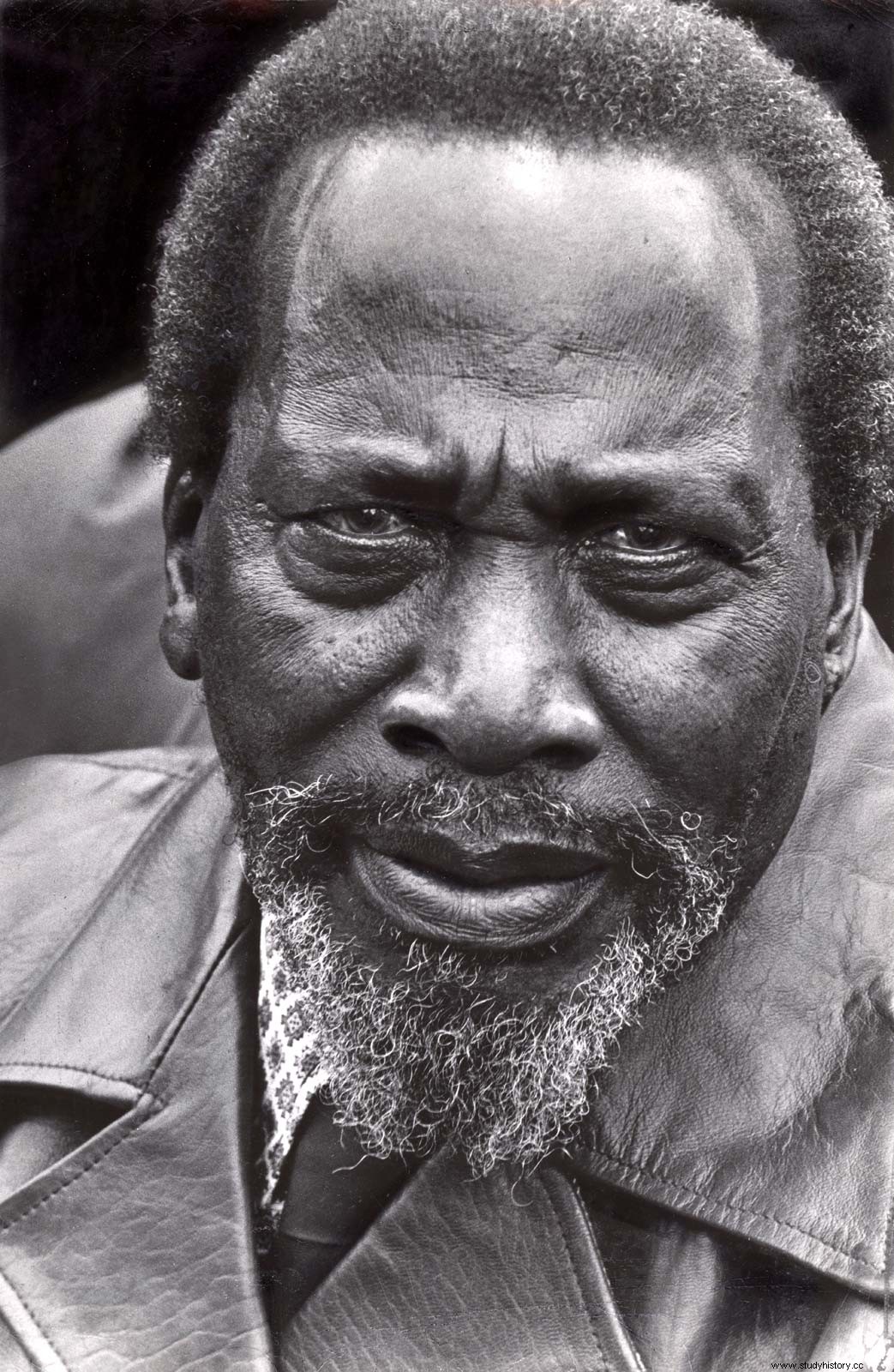

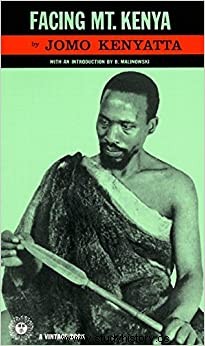

Interestingly, most KAU leaders, especially the future Kenyan Prime Minister (1963-1964) and the President (1964-1978) are Jomo Kenyatta , believed that dignity could only be achieved "when whites and blacks recognized the benefits of African customs and institutions." [26]

Kenyatta and other like-minded athomi was referred to as moderate nationalists , since they tried it both :

- promote progress through (western) education

- and to preserve the best African traditions [27] to create a new culture which would be modified to withstand the pressures of modern conditions.

Moderate nationalists believed that power naturally belonged to elders, and since the majority of KAU members belonged to that age group, they therefore naturally wanted to retain the traditional hierarchical structure of society that was reinforced by moral ethnicity. [28]

This explains why in his most famous anthropological study of the Kikuyu people, 1938 Facing Mount Kenya , Defended the customs of the Kenyatta tribe (including the traditional custom of female circumcision ( clitoridectomy )), hierarchical family, clan, and age grading entities. [29]

In 1946, when he returned from Britain after sixteen years away, Kenyatta became an oldest elder in the Kikuyu tribe and married "to one of the most powerful lineages in Kikuyuland" [30] as well as bought a massive plot of land and built an impressive mansion with a large library. [31]

Moderate nationalist elders such as Kenyatta could thus have exercised moral authority in the local community, especially over landless peasants and poverty-stricken workers, since their wealth enabled them to achieve the greatest possible degree of wiathi .

Therefore, it is now clear why KAU has made no effort to reverse the British drafts of landless Kikuyus after World War II:due to their possession of the highest extent of wiathi , it was natural for them to promote the preservation of the moral ethnicity of the tribes which gave them their power and influence.

In fact, while KAU sent legal objections to white settler farmers to the colonial office, their basic complaints were not directed at the system, but at the ownership and management of the land from foreign lands that they believed had to be owned by them. [32]

Athomi elders did not understand the struggle of young farmers and constantly argued about the importance of hard work and moral discipline to achieve wiathi .

Landless farmers who were expelled from the white settlers' properties they used to work with have initially relied most on KAU's help, and therefore they were most affected by KAU's inability (or unwillingness) to protect their rights. As many senior clan members and chiefs have also begun expelling landless peasants from their land to maximize their own profits, distrust of patrons who rejected Kikuyu's moral bond of reciprocity has escalated further. [33]

Eventually it became clear that, as agents for the crown and as non-supportive borrowers, athomi elders (including KAU) have completely renounced their legitimacy of moral authority.

Squatters facing landlessness and moral extinction now had reason to distrust both their white and black patrons ... [34]

RADIC NATIONALISM

The Mau Mau uprising was therefore seen as only path that can lead to wiathi (political authority / freedom) - that is, the only way that would fulfill Kikuyu's life with meaning.

By promising their supporters ithaka na wiathi , which roughly translates as 'freedom' through land ', the rebels emphasized the cultural significance of wiathi , which makes land conditional to freedom, for the Kikuyu tribes. [35]

Therefore, the Mau Mau uprising was not only seen as an anti-colonial struggle, but also as a struggle within The Kikuyu community - that is, intergenerational conflict over the attainment of political authority [36] grounded in wiathi .

Despite the fact that the majority of the Mau Mau rebels did not seek political independence as they only fought for wiathi , this does not make them any less nationalistic since a nationalist is the one who fights for freedom:

- Since Kikuyu's moral ethnicity equates freedom with land ownership, Mau Mau 'freedom fighters' can rightly be called nationalists. [37]

MAU MAU REBELLION

The movement for 'freedom' through land 'began in the early 1950s when radical nationalists (Mau Mau rebels) began to spread the ritual of Eden from city center to villages. [38]

The ritual with oath was traditionally sworn by elders to strengthen a unified tribal identity through the imposition of thahu or a state of spiritual impurity that was intended to lead to misfortune for a transgressor of the oath of allegiance. [39]

Such an oath ritual was thus a very practical mechanism used by Mau Mau rebels to mobilize the said desperate illiterates as well as to ensure silence among the population in general [40], meanwhile the rebels continued to attack settlements and assassinate European colonizers. [41 ]

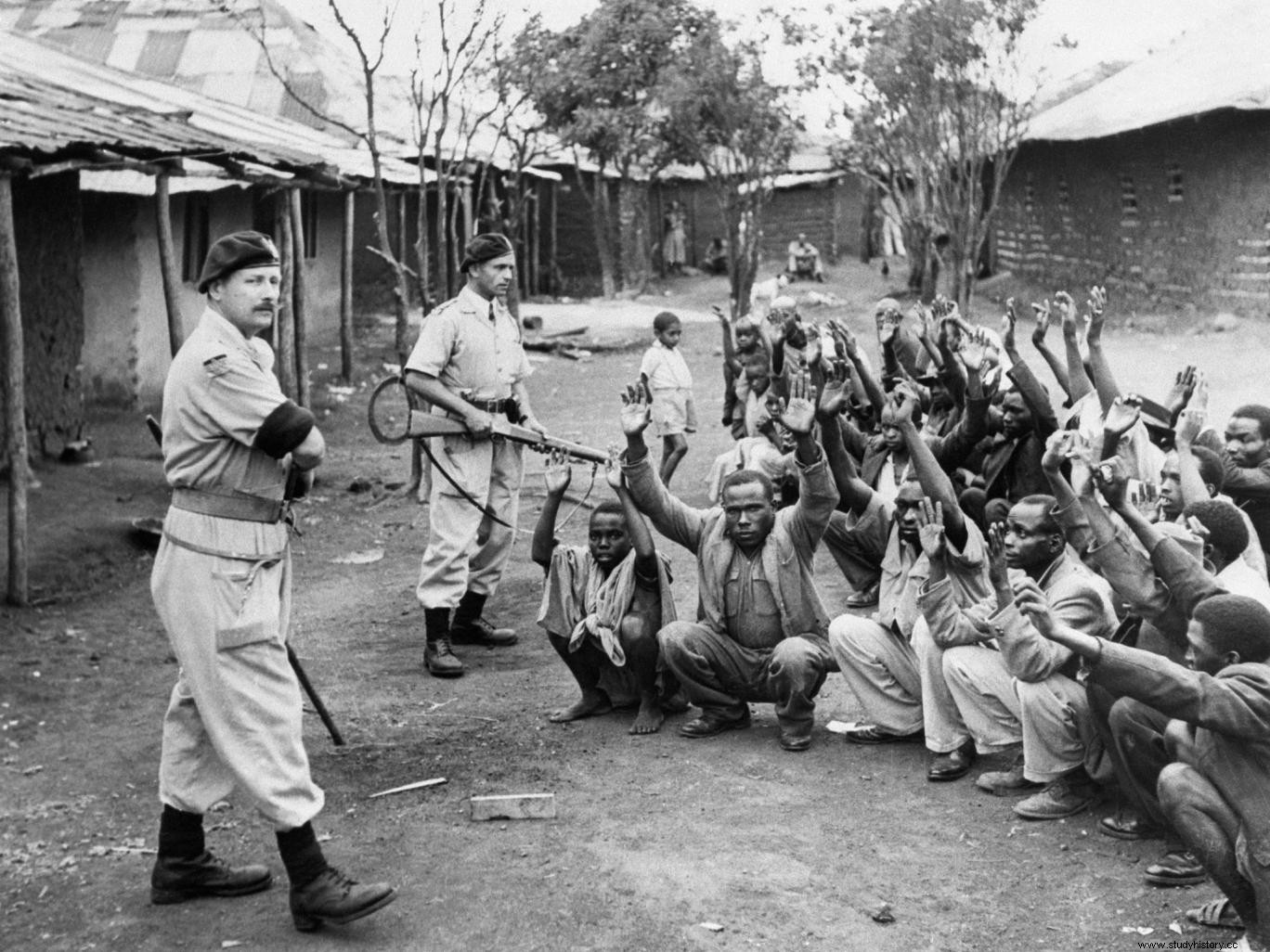

The widespread reports of these acts of violence, including the assassination of loyalist senior chief Waruhiu, have prompted the British government to declare a State of Emergency in October 1952. [42]

THE END OF MAU MAU REBELLION

Despite Mau Mau's initial military successes, the uprising was brutally suppressed by the British (with much help from 'loyalist' and moderate nationalists).

- While rebels killed thirty-five settlers, sixty-three British soldiers, three Asians and 524 African loyalists, it is estimated that British security forces eliminated more than 50,000 XNUMX Mau Mau rebels.

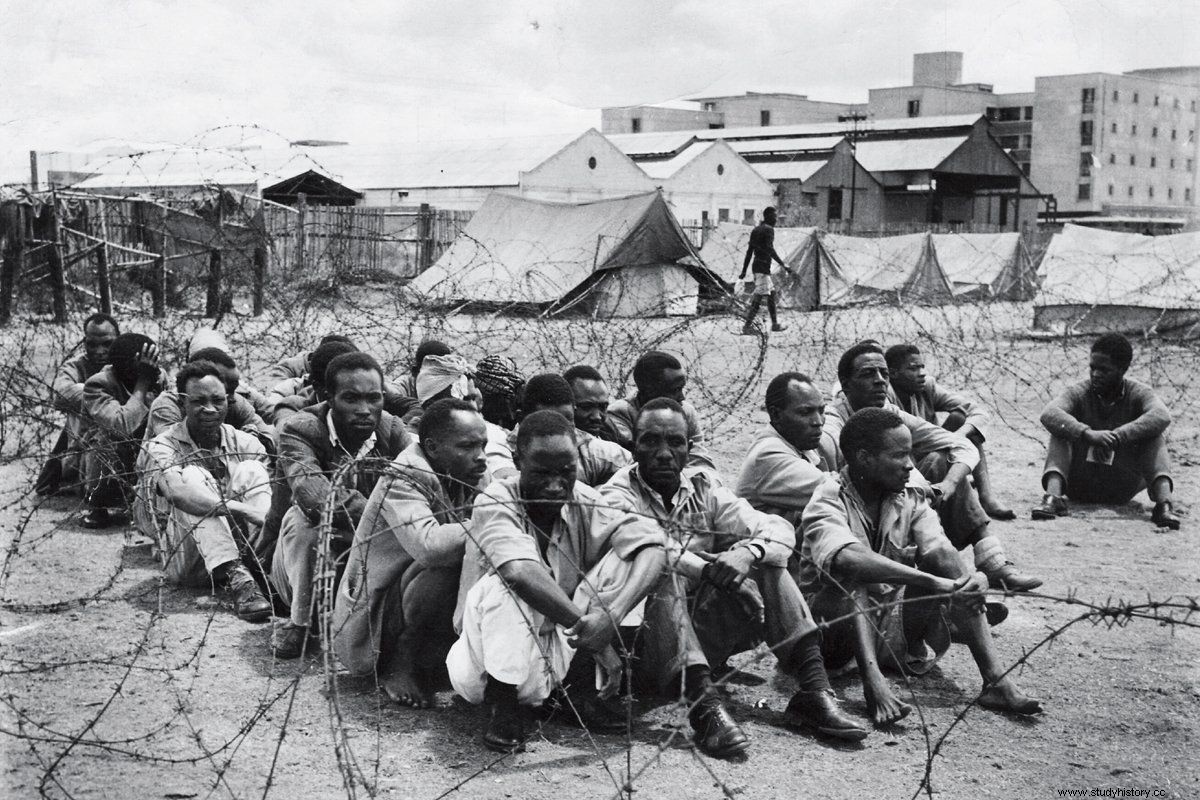

Since the said state of emergency did not prevent Mau Mau rebels from killing more white settlers, the colonial government was forced to step up its security measures by imprisoning and detaining political leaders and civilians suspected of being affiliated with the movement in concentration camps. [43]

One of the most notorious counter-revolutionary operations led by the British against Mau Mau was called 'Operation Anvil' , which took place April 24, 1954:

- 30,000 XNUMX Kikuyu were removed from Nairobi and located in reception camps , where the British, with the help of loyalist informants, screened and discovered the "infected with Mau Mau disease" [44] to be placed in imprisonment (read:concentration) the camps .

- Approximately 80,000 XNUMX Kikuyu were subjected to rehabilitation under the pretext "that men who were so mentally disoriented could not otherwise resume a rational existence." [45]

Since Nairobi was one of the main centers of Mau Mau radicalism, the occupation of the British made aid to the rebels an impossible task.

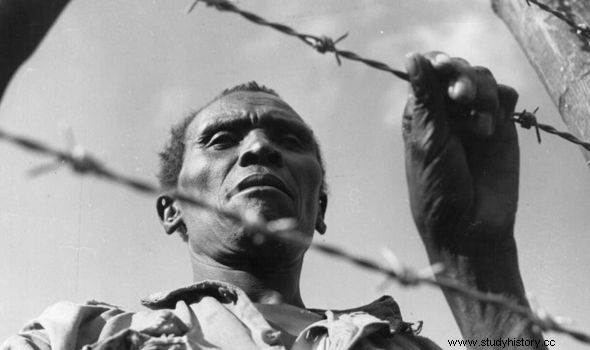

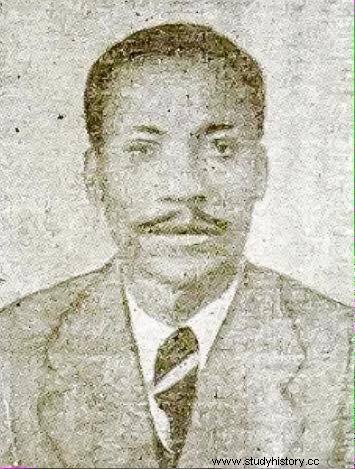

Dedan Kimathi , who was initially an oath administrator, was also arrested, but he was able to bribe a local guard, escape and hide in the Aberdare forest where he later rose to become one of the most prominent leaders of the Mau Mau uprising. [46]

- 21. October 1956, Kimathi was arrested by British forces and hanged in early 1957. [47]

- It was officially believed that he was the last captured Mau Mau.

OTHER REASONS FOR THE MAU MAU DEPOSIT

While the improved security, prisons, prisons, and villagization of Kikuyu by British officials have certainly contributed to influencing the course of the war, there were many other reasons of the Mau Mau defeat.

There are three other very important reasons:

1) MAU MAU SPLIT (Kimathi vs. Mathenge)

- It should be noted that not all radical nationalists has fought only to achieve freedom that revolved around the acquisition of land, since some have also wanted to acquire political independence . The

- Mau Mau Uprising was actually split in line with reading skills .

- For example, while illiterate General Mathenge only aims to achieve freedom through country, knowledgeable Dedan Kimathi besides wiathi has also wanted to create a opponent in the forest. [48] Kimathi's movement was truly anti-colonial .

-

-

- For that reason, Kimathi has founded the Kenya Defense Council and Kenya Parliament to bring order, hierarchy and centralization to scattered Mau Mau forces, as well as touring all young warriors ( itungati ) to present them with their motivational speeches on revolutions, state-building and the importance of the bureaucratic recording of daily work. [49]

- Literacy was also considered essential for inter-branch communication, "with trees acting as mailboxes." [50]

- Thus, in the forest, Kimathi was considered by his followers to be a stats or 'Prime Minister' - "a leader for a new policy for citizens in an orderly, legal and progressive society." [51]

-

-

-

- On the other hand, Mathenge accused Kimathi of being "poisoned by Christianity and Western education" [52], which led him to despise Kikuyu traditions and to use Mathenge unwritten followers for their own selfish goals.

- Mathenge believed that if their revolt was successful, the educated alone would enjoy privileges and deny them to the uneducated itungati "Of whose blood they would have been purchased." [53]

- Mathenge thus formed its own association- Kenya Riigi - which underlined his "constitutional opposition to written orders from official superiors. "[54]

-

- Therefore, the Mau Mau uprising was divided as Kimathi's parliament wanted to establish an independent nation state, while Matenges Riigi has only focused on gaining land .

- This confrontation later undermined Kimathi's leadership of the Mau Mau uprising in general.

2) REWARDS FOR LOYALISM

- The majority of the Kikuyu population has been both loyalist and Mau Mau in different stages of the uprising. [55]

- Ironically, but the same idea of wiathi as unified Mau Mau supporters has contributed to their defeat later, since opponents used the same intellectual tradition to justify their opposition .

- For example, 1950s reform initiated by the Governor of Kenya Evelyn Baring made it possible for loyalty to become the means of self-mastery.

- Since the reform provided free land to those who supported the colonial government, many Mau Mau warriors (especially Mathenge branch) was encouraged to be loyal.

- For example, 1950s reform initiated by the Governor of Kenya Evelyn Baring made it possible for loyalty to become the means of self-mastery.

- Moral ethnicity thus encouraged more Kikuyu to 'change sides' by becoming loyalists who later proved critical of the counter-insurgency operation, "inflicted 50 percent of the Mau Mau casualties in late 1954." [56]

- Ironically, but the same idea of wiathi as unified Mau Mau supporters has contributed to their defeat later, since opponents used the same intellectual tradition to justify their opposition .

3) MAU MAU VOLD

- Moreover, even those who did not support discriminatory British colonial policy in the beginning have been put off by the violence uprising .

- The growing number of civilian casualties and increasing theft suffered by Mau Mau undermined their claims of "keeping the moral high ground." [57]

- The 1953 massacre that took place in the village of Lari When 600 Mau Mau warriors killed around 100 loyalists, including two-thirds women, many hated rebels since "killing women and children was difficult to equate with a struggle for land and freedom." [58]

- The growing number of civilian casualties and increasing theft suffered by Mau Mau undermined their claims of "keeping the moral high ground." [57]

- As we can see, the moral ethnicity of wiathi was used by loyalists and moderate nationalists against Mau Mau also in this case.

- Both loyalists and moderate nationalists came back to the ideals of moral ethnicity to remind everyone that < to achieve wiathi one had to work hard and be disciplined, and that those who became prosperous through theft and violence had to be ashamed and considered criminals. [59] The rebels' use of crime and violence during their "land movement" meant that they "consumed what they had not worked for without regard to the needs of others" [60] and that they tried to obtain by force what they did not have the patience to achieve. through hard work.

- Therefore, the rebels' rejection of work and their crime marked themselves as "criminal, unqualified and ill-equipped to lead Kikuyu" [61] or even as' wild animals' and 'hyenas' because of their preference for stealing. and race. [62]

- The transition to fidelity was therefore explained by the assessment of which, out of radical , moderate or 'loyalist' nationalism offered the most potential road to wiathi . [63]

COMPETITION NATIONALISM

As we can see now, while loyalist and moderate nationalists have confronted each other about the continuing necessity of African customs, both have also confronted some radical nationalists (Eg Mathenge ) on the latter's unwillingness to pursue political independence. By proclaiming that the nation-states were created by 'progressive' colonial nations - that is, modern institutions - loyalists and moderate believed that nationalism a priori could not have been expressed by 'barbaric' Mau Mau peasants who seemed to reject modernity for a single acquisition of land.

On the other hand, knowledgeable Mau Mau (as Kimathi ), WHO did seeks political independence and did not want to return to 'barbaric tribal resistance', has rejected everything 'western' and was against moderate nationalists' moral authorities based on domestic discipline rooted in wiathi [64]. They questioned the extent to which the relationship between generations must be reconsidered to ensure that the younger generation had some freedom and was thus less dominated by the older ones. [65]

The conflict between (all) radical and moderate nationalists was thus largely rooted in argument between generations between men who "contested the power of the elders to determine the rules of honor" [66] and elders who wanted to preserve their traditional authority.

To preserve their traditional influence, moderate nationalists went back to Kikuyu's moral ethnicity by emphasizing the fact that the attainment of wiathi was not only rooted in land ownership, but also in hard work and moral discipline.

During KAU's annual conference in Nairobi on July 6, 1948, for example, Kenyatta emphasized his admiration for hard work as the only 'tools' where Kenyans can achieve independence:

“Africans want the freedom to govern themselves. But if we want freedom, we must escape idleness. Freedom does not come from heaven. We have to work and work hard […]. If we use our hands, we will be men ... I do not want to see any able-bodied men running around without work. ” [67]

For the same reason, he was opposed to the implementation of land redistribution - that is, "wanting" free things "that had not been earned by labor" [68] - since he believed that since Kenyans wanted to flourish as a nation, they had to demand equality. :"equal pay for equal work." [69]

This desire to retain his moral authority therefore explains why Kenyatta, who became independent Kenya's first Prime Minister in 1963, and his newly formed Kenya African National Union (KANU) has ignored the demands of surviving Mau Mau hunters for land redistribution and the expulsion of loyalists and moderates from lands seized from them. [70]

It also explains why KANU suppressed the history of Mau Mau's battles while praising moderate and loyal nationalists "If 'loyalist cooperation' with Britain had enabled them to become the rulers of a supposedly independent, but in reality neo-colonial Kenya. "[71]

Speaking at the Kenyatta Day Rally in Nairobi on October 20, 1967, Kenyatta stated:

"We all fought for Uhuru [freedom] , and only the cowards used to hide under beds while others struggled to talk about 'freedom fighters' [Mau Mau] ». [72]

Undoubtedly, this KANU-promoted is 'official nationalism' has strongly concealed the aforementioned contributions and struggles of Mau Mau 'freedom fighters', thus emphasizing the continuing split between radical and moderate / loyalist nationalists .

CONCLUSION

It is important for a historian (or anyone for that matter) to understand that historical memory can be contradictory in response to today's changing realities.

For example, Kimathi was perceived as a guerrilla fighter in the 1950s, "a nationalist in the 1960s and 1970s, an underground subversive in the 1980s, a Democrat in the early 1990s and a victim of persecution against Kikuyu in the 2000s. century. "[73]

Therefore, it is crucial to be critical of historical sources - that is, to study about competing nationalism which not only depicts a state's official history of nationalism, but also various other internal struggles that underpinned it.

By understanding all 'types' of nationalism, it becomes clear why, how a particular event took place, and may help eliminate confusion in the future where even "tomorrow today will inevitably be different." [74]

If historians want to understand the past for their own sake instead of being contextualized to fit modern realities, then competing nationalism must be taken into account.

Bibliography:

- Angelo, Anaïs. "Jomo Kenyatta and the Suppression of the 'Last' Mau Mau Leaders, 1961–1965." Journal of Eastern African Studies 11, No. 3 (July 2017):442–59. https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/17531055/v11i0003/442_jkatrotmml1.xml.

- Asante, Molefi Kete. "Africa regains consciousness in a pan-African explosion." I Afrikas historie:Jakten på evig harmoni , 259–92. New York og London:Routledge, 2007.

- Berman, Bruce J. "Nasjonalisme, etnisitet og modernitet:Paradokset til Mau Mau." Canadian Journal of African Studies 25, nr. 2 (januar 1991):181–206. https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/00083968/v25i0002/181_neamtpomm.xml.

- Gren, Daniel. Beseirer Mau Mau, oppretter Kenya:Motinsurgering, borgerkrig og avkolonisering . Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Gren, Daniel. "Fienden innen:lojalister og krigen mot Mau Mau i Kenya." Journal of African History , no. 48 (2007):291–315. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-african-history/article/enemy-within-loyalists-and-the-war-against-mau-mau-in-kenya/5B04B9B277281F231E4D138A32C6651C.

- Gren, Daniel. "Søket etter restene av Dedan Kimathi:Politikken om død og minnesmerke i post-kolonial Kenya." Fortid og nåtid:Relikvier og levninger , 2010. august, 301–20. https://search-proquest-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/docview/1035996409?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14771.

- Hobson, Fred. "Frihet som moralsk byrå:Wiathi og Mau Mau i koloniale Kenya." Journal of Eastern African Studies 2, nr. 3 (november 2008):456–70. https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/17531055/v02i0003/456_famawammick.xml.

- Kenyatta, Jomo. "Årlig konferanse for KAU." Tale, i Lider uten bitterhet:grunnleggelsen av Kenya -nasjonen . Juli 6, 1948. https://archive.org/stream/sufferingwithout0000keny#page/44/mode/2up.

- Kenyatta, Jomo. "Oppstart av gutter og jenter." I Mot Mount Kenya:Gikuyus stammeliv , 125–48. Vintage bøker, 1938.

- Kenyatta, Jomo. "Jomo Kenyatta:Den afrikanske unionen i Kenya er ikke Mau Mau." 26. juli 1952. http://www.artsrn.ualberta.ca/amcdouga/Hist247/winter 2010/essay_project/kenyattaspeech.htm.

- Kenyatta, Jomo. “Kenyatta Day.” Tale, i Lider uten bitterhet:grunnleggelsen av Kenya -nasjonen . 20. oktober 1967. https://archive.org/stream/sufferingwithout0000keny#page/340/mode/2up

- Kenyatta, Jomo. "Den afrikanske unionen i Kenya er ikke Mau Mau." Tale. 26. juli 1952. http://www.artsrn.ualberta.ca/amcdouga/Hist247/winter 2010/essay_project/kenyattaspeech.htm.

- Kyle, Keith. "Politikken til Mau Mau." I Politikken for Kenyas uavhengighet , 45–65. Palgrave, 1999.

- Larmer, Miles og Baz Lecocq. "Historisere nasjonalisme i Afrika." Nasjoner og nasjonalisme 24, nei. 4 (oktober 2018):893–917. https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/13545078/v24i0004/893_hnia.xml.

- Lonsdale, John. "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after Second World War." Journal of African Cultural Studies 13, nei. 1 (juni 2000):107–24. https://search-proquest-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/docview/60580419?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14771.

- Lonsdale, John. "Mau Maus debatter om rettssaken." I Dedan Kimathi om rettssak:Colonial Justice and Popular Memory in Kenya's Mau Mau Rebellion , redigert av Julie MacArthur, 258–83. Ohio University Press, 2017.

- Lonsdale, John. "Moralisk etnisitet, etnisk nasjonalisme og politisk tribalisme:saken om kikuyuen." I Staat Und Gesellschaft i Afrika:Erosjoner og reformprosesser , redigert av Peter Meyns, 93–106. LIT VERLAG, 1996.

- MacArthur, Julie. "Innledning:Rettssaken mot Dedan Kimathi." I Dedan Kimathi om rettssak:Colonial Justice and Popular Memory in Kenya's Mau Mau Rebellion , redigert av Julie MacArthur, 1–35. Ohio University Press, 2017.

- Odhiambo, ES Atieno. "Matunda Ya Uhuru, Fruits of Independence:Seven Theses on Nationalism in Kenya." I Mau Mau og nasjon:våpen, autoritet og fortelling , redigert av ES Atieno Odhiambo og John Lonsdale, 37–45. Oxford:James Currey, 2003.

- Savage, Donald C. "Kenyatta and the Development of African Nationalism in Kenya." Internasjonalt tidsskrift 25, nr. 3 (1970):518-37. https://search-proquest-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/docview/37661849?accountid=14771&pq-origsite=summon.

Merknader:

[1] Miles Larmer og Baz Lecocq, "Historisering av nasjonalisme i Afrika," Nasjoner og nasjonalisme 24, nei. 4 (oktober 2018):s. 893-917, https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/13545078/v24i0004/893_hnia.xml, 900.

[2] Larmer, Ibid, 896.

[3] Ibid, 896.

[4] ES Atieno Odhiambo, "Matunda Ya Uhuru, Fruits of Independence:Seven Theses on Nationalism in Kenya," i Mau Mau og nasjon:våpen, autoritet og fortelling , red. ES Atieno Odhiambo og John Lonsdale (Oxford:James Currey, 2003), s. 37-45, 38.

[5] Fred Hobson, "Freedom as Moral Agency:Wiathi and Mau Mau in Colonial Kenya," Journal of Eastern African Studies 2, no. 3 (november 2008):s. 456-470, https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/17531055/v02i0003/456_famawammick.xml, 457.

[6] Daniel Branch, Beseirer Mau Mau, oppretter Kenya:Motinsurgering, borgerkrig og avkolonisering (Cambridge University Press, 2009), 3.

[7] John Lonsdale, "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after Second World War," Journal of African Cultural Studies 13, nei. 1 (juni 2000):s. 107-124, https://search-proquest-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/docview/60580419?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14771, 115.

[8] Hobson, Ibid, 464.

[9] Hobson, Ibid, 456.

[10] Hobson, Ibid, 460.

[11] Hobson, Ibid, 459.

[12] Hobson, Ibid, 460.

[13]Gren, Beseirer Mau Mau, oppretter Kenya:Motinsurgering, borgerkrig og avkolonisering , Ibid, 132.

[14] Gren, Beseirer Mau Mau, oppretter Kenya:Motinsurgering, borgerkrig og avkolonisering , Ibid, 16.

[15] Hobson, Ibid, 159.

[16]Lonsdale, "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after Second World War," Ibid, 110.

[17]Lonsdale, "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after Second World War," Ibid, 118.

[18]Donald C. Savage, "Kenyatta and the Development of African Nationalism in Kenya," Internasjonalt tidsskrift 25, nei. 3 (1970):s. 518 -537, https://search-proquest-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/docview/37661849?accountid=14771&pq-origsite=summon, 532.

[19] Bruce J. Berman, "Nasjonalisme, etnisitet og modernitet:Paradokset til Mau Mau," Canadian Journal of African Studies 25, nei. 2 (januar 1991):s. 181-206, https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/00083968/v25i0002/181_neamtpomm.xml, 187.

[20] Berman, Ibid, 188.

[21]Berman, Ibid, 187.

[22] Berman, Ibid, 188.

[23] Ibid, 188.

[24]Berman, Ibid, 199.

[25]Savage, Ibid, 533.

[26] Savage, Ibid, 533.

[27] Ibid, 533.

[28] Savage, Ibid, 534.

[29]Jomo Kenyatta, "Initiering av gutter og jenter", i Mot Mount Kenya:Gikuyus stammeliv (Vintage Books, 1938), s. 125-148, 125.

[30] Lonsdale, "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after the Second World War," Ibid, 114.

[31] Ibid, 114.

[32] Ibid, 114.

[33]Lonsdale, "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after Second World War," Ibid, 118.

[34] Ibid, 118.

[35] Hobson, Ibid, 459.

[36]Hobson, Ibid, 460.

[37]Berman, Ibid, 189.

[38] Julie MacArthur, "Introduction:The Trial of Dedan Kimathi," i Dedan Kimathi om rettssak:Colonial Justice and Popular Memory in Kenya's Mau Mau Rebellion , red. Julie MacArthur (Ohio University Press, 2017), s. 1-35, 6.

[39] Gren, beseiret Mau Mau, opprettet Kenya:motinsurgering, borgerkrig og avkolonisering, Ibid, 35.

[40]Gren, beseire Mau Mau, opprette Kenya:motinsurgering, borgerkrig og avkolonisering, Ibid, 2.

[41]MacArthur, Ibid, 6.

[42] Ibid, 6.

[43] Molefi Kete Asante, "Afrika gjenvinner bevissthet i en panafrikansk eksplosjon", i Afrikas historie:Jakten på evig harmoni (New York og London:Routledge, 2007), s. 259-292, 284.

[44] Keith Kyle, "The Politics of Mau Mau," i Politikken for Kenyas uavhengighet (Palgrave, 1999), s. 45-65, 61.

[45] Ibid, 61.

[46] MacArthur, Ibid, 6.

[47]Asante, Ibid, 284.

[48] MacArthur, Ibid, 6.

[49] MacArthur, Ibid, 7.

[50] John Lonsdale, "Mau Mau's Debates on Trial", i Dedan Kimathi om rettssak:Colonial Justice and Popular Memory in Kenya's Mau Mau Rebellion , red. Julie MacArthur (Ohio University Press, 2017), s. 258-283, 267

[51] MacArthur, Ibid, 6.

[52] MacArthur, Ibid, 7.

[53]Lonsdale, "Mau Mau's Debates on Trial," Ibid, 268.

[54] Ibid, 268.

[55] Gren, beseiret Mau Mau, opprettet Kenya:motinsurgering, borgerkrig og avkolonisering, Ibid, 14.

[56]Gren, Ibid, 5.

[57] Gren, Ibid, 137.

[58] Gren, Ibid, 59.

[59]Gren, Ibid, 133.

[60]Gren, Ibid, 137.

[61] Gren, Ibid, 140.

[62] Gren, Ibid, 142.

[63] Gren, Ibid, 18.

[64]Lonsdale, "Mau Mau's Debates on Trial," Ibid, 263.

[65]Lonsdale, "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after Second World War," Ibid, 115.

[66]Lonsdale, "KAU's Cultures:Imaginations of Community and Constructions of Leadership in Kenya after Second World War," Ibid, 114.

[67]Jomo Kenyatta, "Årlig konferanse for KAU," i Lider uten bitterhet:grunnleggelsen av Kenya -nasjonen . Juli 6, 1948. https://archive.org/stream/sufferingwithout0000keny#page/44/mode/2up.

[68]Daniel Branch, "The Search for the Remains of Dedan Kimathi:the Politics of Death and Memorialization in Post-Colonial Kenya," Fortid og nåtid:Relikvier og levninger , August 2010, s. 301-320, https://search-proquest-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/docview/1035996409?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14771, 307.

[69] Jomo Kenyatta, "Jomo Kenyatta:Kenya African Union Is Not the Mau Mau," (26. juli 1952), http://www.artsrn.ualberta.ca/amcdouga/Hist247/winter 2010/essay_project/kenyattaspeech.htm.

[70]Anaïs Angelo, "Jomo Kenyatta og undertrykkelsen av de 'siste' Mau Mau -lederne, 1961–1965," Journal of Eastern African Studies 11, no. 3 (juli 2017):s. 442-459, https://journals-scholarsportal-info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/details/17531055/v11i0003/442_jkatrotmml1.xml, 444.

[71]Kenyatta, "Jomo Kenyatta:Kenya African Union Is Not the Mau Mau," Ibid.

[72]Jomo Kenyatta, "Kenyatta Day", i Lider uten bitterhet:grunnleggelsen av Kenya -nasjonen . 20. oktober 1967. https://archive.org/stream/sufferingwithout0000keny#page/340/mode/2up.

[73] Gren, "The Search for the Remains of Dedan Kimathi:the Politics of Death and Memorialization in Post-Colonial Kenya," Ibid, 319.

[74]Lonsdale, "Mau Mau's Debates on Trial," Ibid, 270.