The clash that determined the fate of Poland did not take place on the battlefield, but in the palace chambers, in the course of secret negotiations. Casimir the Great agreed to pay the amount for which 20 castles, 60 towns or ... 40,000 cows could be bought. It was worth it.

The newly revived Polish kingdom was in a critical situation. The mighty king of Bohemia, John of Luxembourg, about Władysław the Short he said that he was only "the king of Krakow" and not the legal ruler of the entire Polish state. Believing that the Wawel throne really deserved him, he had already organized one military expedition to the north and was preparing another.

At the same time, Poland became involved in an almost permanent war with the Teutonic Order, which was growing in strength and enjoyed great press in the West. Knights in white cloaks adorned with a crucifix plundered and appropriated entire stretches of the kingdom.

In 1329, Włocławek fell into their hands, where they stripped the local cathedral without hesitation. Then they robbed Nakło and Raciąż, where the treasures of Kujawy bishops were buried. They also took over Radziejów - the same town where the Queen (and then the Duchess) Jadwiga Kaliska hid for several years.

In 1331, the Teutonic Knights sacked Gniezno and Żnin. In 1332, the whole of Kujawy - Łokietek's fatherhood, the country of his youth and the province most faithful to him - fell into enemy hands. During the war, Poles were constantly on the defensive. Even the biggest battle of this conflict, fought at Płowce in 1331 , it ended not with a win, but a draw at best. It delayed the inevitable collapse of Kujawy for a year.

Władysław Łokietek after the battle of Płowce. Image from the Jubilee Album published in 1910.

New King, Old Problems

On March 2, 1333, devastated by constant defeats and bent under the weight of old age, Władysław the Short gave up his ghost. He has suffered, as is suspected, an attack of paralysis. 23-year-old Kazimierz became the king. And it was on his shoulders that the task of saving the country, on which two powerful neighbors - and potential invaders - was waiting.

He began the task not with a sword in his hand, but with reasonable thought, which in the future would give him the nickname of Casimir the Great. It is difficult to decide today to what extent he acted on his own. It seems highly probable that it was not even him but the powerful women of the king's entourage that played the decisive role:his mother, Dowager Queen Jadwiga and sister, Queen of Hungary Elżbieta Łokietkówna .

They tightened the already existing alliance between Poland and Hungary. And they helped to make it a tool that would lead the Piast country out of deadly isolation.

An indispensable ally

Hungary, ruled by the ailing Karol Robert of the Anjou dynasty, was in a period of extraordinary prosperity. It was during these years that they became the most important gold mining center in Europe. And not only in Europe - historians estimate that even a third of the entire global demand for this precious metal was met by the Magyars.

The Hungarians had mountains of gold, troops of punitive soldiers, as well as a group of blindly devoted to the king (or rather:effectively broken and intimidated) barons. Some Hungarian historians even claim that it was an absolute monarchy, hundreds of years before absolutism took hold in the West.

Karol Robert and Elżbieta Łokietkówna they also had a real sea of people. The empire, growing in strength, was inhabited by up to three million subjects, while the state of Kazimierz could be inhabited by eight hundred, or at most nine hundred thousand people.

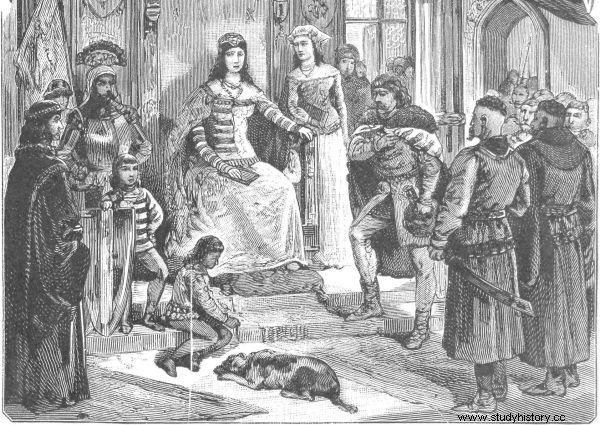

Elzbieta Łokietkówna in the vicinity of the manor house in the graphics of Fr. Pillati

The disproportion was also huge in the field of diplomacy. Poland was treated as a seasonal country, and often even - like a whipping boy who should not jump on older people. Most of the rulers of Europe did not even consider the Piasts to be true kings, because the right to the title of Polish monarch was also claimed by the ruler of Bohemia. When the Pope agreed to the coronation of Elbow-high in 1320, first he had to be bribed and persuaded to turn a blind eye to these competing claims.

Karol Robert, meanwhile, enjoyed universal respect at this stage. Czech Luxembourgs were friends with him; the authorities of the Teutonic Order respected him. He was not a man to refuse. When in 1335 he invited neighboring rulers to his castle in Visegrád, everyone expected to visit came.

Extremely expensive meeting

The King of Bohemia, John of Luxembourg, and his son Charles, who ruled in Moravia, appeared. The Saxon prince Rudolf came, as well as the prince of Brzeg in Silesia, Bolesław III Rozrzutny. A delegation of the Teutonic Knights, headed by two commanders, arrived. Finally, now five years after the previous disastrous visit , the Polish king Kazimierz also showed up.

John of Luxembourg. A print showing the bust of the king, end of the 19th century

Along with each of the dynasties, huge processions, consisting of even hundreds of courtiers, knights, and servants, came. In total, thousands of greedy and often also used to living in luxury foreigners. Karol Robert guaranteed that he would provide them all with food, lodging and proper entertainment. He was facing a huge scale and fabulously expensive undertaking.

According to the native Hungarian chronicle, two and a half thousand loaves of bread were laid out on the tables during the dinner given to the King of Bohemia and his companions. A similar feast with the participation of a Polish retinue, apparently more modest, consumed 1,500 loaves. One hundred and eighty barrels of wine were placed on it. And yet, in addition to food and drinks, you also had to spend on the appropriate gifts.

The Czech king, John of Luxembourg, received from his Hungarian friend fifty silver cups, two decorated quivers, three beautiful belts, an exclusive chessboard, two allegedly priceless saddles, an expensive knife and pearls. More modest gifts also went to the other guests, all in order to create the right atmosphere for political arrangements.

A true picture of medieval Poland. History without a powder in the new book by Kamil Janicki:"We will give the Polish empire". You can buy it at empik.com

Conversations that changed the fate of Poland

It was November 1335 and in the most magnificent Hungarian palace, which at that time even played the role of the capital of the state, a treaty was concluded which allowed not only to save Poland, but also to introduce it to Europe as an equal player with its neighbors.

The King of Bohemia, under the pressure of the Hungarian ruler, gave up his claims against the Piasts, although he did not do it (of course) for free. In return, Kazimierz was to relinquish any rights to Silesia, one of the most important historical provinces of the Piast state. Moreover, the king was to pay a hefty ransom.

For his resignation from the title of the ruler of Poland, John of Luxembourg demanded twenty thousand copies of Prague groszy. The sum - as recorded in this way by all history books - does not sound particularly impressive. Meanwhile, twenty thousand copies is as much as one million two hundred thousand coins. A total of over three and a half tons of silver. For that amount of metal, one could buy, for example, four thousand horses, seventeen thousand swords or ... forty thousand cows. The sum expected by the Czechs would also be enough to acquire twenty magnificent castles or even sixty towns.

Ruins of the castle in Visegrád. Contemporary photo (photo:Peter89ba; CC0)

It was a truly astronomical amount. Above all:remaining beyond the reach of Kazimierz, which is still in the past and burdened with war costs.

Brother-in-law, mediator, resident

The king knew well that without peace with the Czechs he would not be able to go straight. He agreed to pay two-thirds of the requested amount. The rest of the debt was to be settled by Easter at the latest. So he got just over four months to make a fortune.

Desperate, he agreed to these conditions, but at the last moment he was rescued by his wealthy brother-in-law. Karol Robert lent Kazimierz the amount he needed and as a result, nothing was blocking the signing of the pact anymore.

Karol Robert at the end of his life. Early 19th century lithograph.

The kings of Bohemia and Poland made peace, and then an alliance. In Visegrad, it was also possible, at least temporarily, to end the conflict between the Piasts and the Teutonic Knights. Kazimierz was returning to Poland very impoverished, but calm about his immediate future.

The entire congress was to go down in history as one of the most important events in the common history of the countries in the region. To this day, in memory of the meeting in 1335, the cooperation of the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovakia takes place within the informal "Visegrad group".

Selected bibliography:

The article was based on materials collected by the author during the work on the book "Ladies of the Polish Empire. The Women Who Built a Power " . Some of these items are shown below. Full bibliography in the book.

- Dąbrowski J., Elżbieta Łokietkówna 1305-1380 , Universitas, Krakow 2007.

- Engel P., The Realm of St. Stephen. A History of Medieval Hungary 895-1526 , I.B. Tauris, London – New York 2001.

- Kiryk F., The Great King and His Successor , National Publishing Agency 1992.

- Klápště J., The Czech Lands in Medieval Transformation , Brill, Leiden – Boston 2012.

- Kurtyka J., The reborn kingdom. The monarchy of Władysław Łokietek and Casimir the Great in the light of more recent research , Societas Vistulana, Krakow 2001.

- Rácz G., The Congress of Visegrád in 1335:Diplomacy and Representation , Hungarian Historical Review, vol. 2 (2013).

- Szczur S., Circumstances of the renunciation of Silesia by Casimir the Great , "Historical Studies", vol. 30 (1987).

- Szczur S., Visegrad Convention of 1335 , "Historical Studies", vol. 35 (1992).

- Wyrozumski J., Casimir the Great , Ossolineum, Wrocław 2004.