London was called little Europe. It is hard to believe how many governments and how many rulers took refuge in the Isles to observe Hitler's triumphal march from a distance. Instead of uniting in a common fight against the occupier, they showed a display of shameful partyism and arrogance. Not all of them, of course.

Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzem, who managed to take a closer look at the actions of the occupier in his native Netherlands, after getting to Great Britain, was amazed at how the governments that took refuge in London were working. He commented on this directly, stating that in the greenhouse atmosphere of the capital of England, plots were plowed like toadstools by people with many personal and political accounts to settle.

Governments that experienced the humiliation of defeat in their own countries and had to flee, in a foreign land more readily responded to trauma, fighting fiercely in their own ranks.

Lynne Olson, author of the new book "Island of Last Hope ", He quotes from Hazelhoff Roelfzem, for whom meeting officials from his home country was like a cold shower:

They lived in a world of positions and salaries, promotions and raises that was, after fifteen months of occupation for us refugees, as illusory as prison cells and firing squads for them.

"Munich complex". Czechoslovakia

Apart from politicians caught up in a network of conspiracies and struggles in exile, London was also visited by those who were genuinely active. Edvard Beneš was one of them.

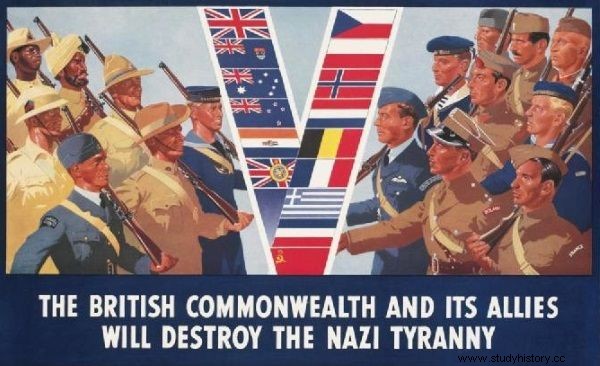

World War II propaganda poster (photo:public domain).

Czechoslovakia, which he ruled until recently, was the first victim of Adolf Hitler. Under the Treaty of Munich, concluded on September 30, 1938, France and Great Britain made it possible for Germany to seize 40% of the country's territory. The great powers deluded that they would appease the Führer and avert the threat of a war.

Edvard Beneš was forced by Hitler to resign as prime minister a few days after the conclusion of the Munich Agreement, after which he left the country. On the news of the outbreak of the war, however, he immediately went to London and claimed that he was the rightful leader of Czechoslovakia, and the government that succeeded him ceased to be legal when it became a puppet of the Germans.

The first two years of Edvard Beneš's activity were, as Lynne Olson emphasizes in the book "The Island of Last Hope" , sometimes frustration and humiliation. The same Nevile Chamberlain, who until recently signed the bandit Munich Agreement, now expressed indignation at the attitude of the former prime minister of Czechoslovakia. Beneš was informed that he could be granted political asylum, but on a certain condition - while in Great Britain he had absolutely no involvement in politics.

President of Czechoslovakia, Edvard Beneš, visits the President of Poland, Stanisław Wojciechowski in 1925.

It was a personal insult for the Czech. While he eventually gained recognition for his position, he never forgot his humiliation.

"Grumpy and arrogant". France

Charles de Gaulle was never elected for that. Nevertheless, as Lynne Olson emphasizes, he insisted that he was the only leader of the struggling and undefeated France. British politicians hated the shoe he was dripping on, nor did they like his Free French. His surroundings were a real arena where people from all walks of life fought constantly and were only loyal to de Gaull.

As one of Winston Churchill's government ministers noted in his diary:

All French immigrants tear cats together. They come to me and tell me how horrible everyone else is.

The Free French were held together only by loyalty to the general, though he was not a good-natured uncle. He could sooner be characterized as a bastard and arrogant who looked down on everyone, even those who wanted to support his cause.

De Gaulle was so harsh on those willing to join him that he discouraged many of them. This was the case of one of the French naval officers who, disappointed with the attitude of the Free French leader, left them to pickle in their own sauce, returned to France and joined the resistance leaders.

Scruffy Queen

The Dutch Queen Wilhelmina showed a completely different attitude after her escape to Great Britain. Although in the country she lived in a golden cage and had no special influence on politics, in London she firmly took the reins of government. Now she was in full power and was using it with all her might.

Queen Wilhelmina reading an uplifting speech to the Dutch. (Photo:public domain)

Unlike many émigré leaders, she obeyed, and the fact that she displayed a very firm, even belligerent attitude gave her respect. Even before leaving the Netherlands, she repeatedly showed what she thought about the Führer, and called the representatives of the Third Reich bandits. The real position of the rebellious queen became very apparent when a few unbrave politicians recommended that she leave London and move to the Dutch East Indies on the other side of the globe. The Queen was furious.

She immediately decided to clean up - she firmly refused to leave and ordered her secretary to shoot her if she were to fall into the hands of the Germans, and forced her resignation at the premiere.

Wilhelmina, living in London, opened herself up to ordinary Dutch people, in particular to those who managed to flee the country and get to Great Britain. They were called "English tourists". The Queen often invited these people to her home for tea in order to get to know the mood of the people in the country and learn as much as possible about the current situation.

George VI had to deal not only with Hitler, but with a whole host of demanding state leaders who had taken refuge in his country. (photo:public domain)

Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema in his memoirs compared the meeting with government officials who shuddered at the words "occupation" or "secret contacts" and were "too busy" to read the latest news from the country. Meanwhile, the Queen listened to him with calm and respect, and then contacted the head of Dutch intelligence.

Twenty-five countries… in one city

During the war, the British government had to deal with a whole host of foreign rulers and politicians who, after their countries were occupied by enemies, sought refuge in London. The emigrant governments or royal families of Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Ethiopia, Estonia, France, Georgia, Greece, India, Korea, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Iran, the Philippines appeared in the English capital, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Thailand, Ukraine and Yugoslavia.

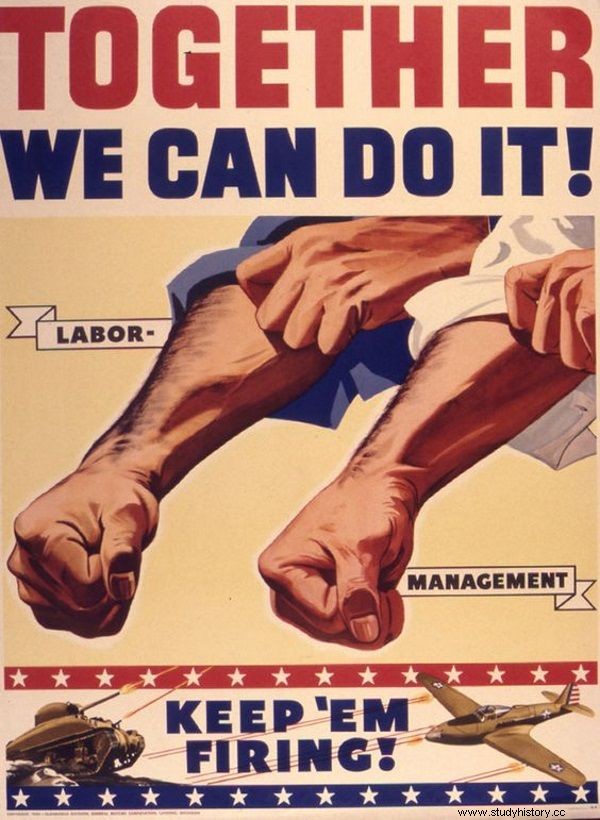

The rules of the game in the London crucible really changed only after joining the fight of "Uncle Sam". (photo:public domain)

Each of these countries had their own interests, intersecting constantly, and it seemed almost impossible to control this chaos. For this purpose, the United States had as many as two embassies in London. The first, the largest and most important diplomatic mission of the country was to serve British-American relations. The second, microscopic in comparison to it, was supposed to mediate relations with the governments in exile.

After the US entered the war, governments in London began to notice a disturbing trend. It became more and more obvious that the future fate of the world would not be determined by any international community understood, but only by the most powerful powers. The rest was left to watch and ... argue, so far.

Buy the book at a discount on empik.com: