Freedom, equality, fraternity ... and the guillotine. The modern decapitation machine was initially a symbol of progress. She quickly turned into an instrument of terror, beheading the royal heads as ruthlessly as the bourgeoisie. Until she finally turned against the children of the revolution. Exactly how many people have fallen victim to it?

The knife whistles, the head falls, the blood spurts, the man is gone. Thanks to my machine, I could make your heads jump in the blink of an eye, leaving you with only a slight chill on your neck. On October 10, 1789, MP Joseph-Ignace Guillotin praised his design of the decapitation device.

At the same time, the progressive doctor suggested that the system of punishments, so far differentiated according to the status of the convict, be standardized. This also applied, of course, to the death penalty. Guillotin wanted everyone to be beheaded without exception. He considered this method, then reserved only for noble births, as the most humane.

The rather awkward speech caused that both in October and December, when he renewed his proposal, was simply laughed at by the National Assembly . The moods changed only in the second half of 1791. At that time, the penal code contained a provision that all those sentenced to death would be beheaded. And in March 1792, consultations began on the design of the machine by which the sentences would be carried out.

At this stage, the matter was not dealt with by Guillotin, who is still associated with the guillotine, but by another doctor - Antoine Louis. The first device according to his idea was made by Tobias Schmidt, a German harpsichord producer. In April 1792 the machine, sometimes referred to as "Louison" or "Louisette", was ready to go. Nobody expected it to soon become one of the main symbols of the French Revolution. Especially its abuses.

Father of the guillotine himself. Portrait of an unknown artist (source:public domain).

Shy starts… and fast acceleration

The first execution in the new style took place on April 25, 1792. The "honor" of testing Dr. Louis' project (in which the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson also contributed) went to Jacques-Nicolas Pelletier, sentenced to death for assault and theft. In the Grève square, where the device had been installed, a crowd had gathered.

Everyone, including the Parisian prosecutor Pierre Louis Roederer, and Lafayette, commander of the National Guard, were slightly flustered. It turned out, however, that there was no cause for concern. The device worked smoothly and the whole process was quick and easy ... And even too quiet and too fast, at least according to the people who crowded around the guillotine, thirsty for the spectacle.

The anthropologist Dr. Frances Larson, in her book entitled "The History of the World by Beheaded Heads Described," describes the crowd's reaction as follows:

The first witnesses to death under the guillotine in the 1890s felt disappointed. They were used to more drama . The machine was running too fast, automatic, there was nothing to look at. Errors were rare, there was no cause for confusion, and there was virtually no interaction with the convict on the scaffold.

However, while the performance itself was disappointing, the effectiveness of the new machine was admired. And it didn't take long to start taking advantage of its possibilities. The first more numerous executions, as the grandson of the Paris executioner noted in the history of the Sanson family, took place in October 1792. Several people were beheaded in one day.

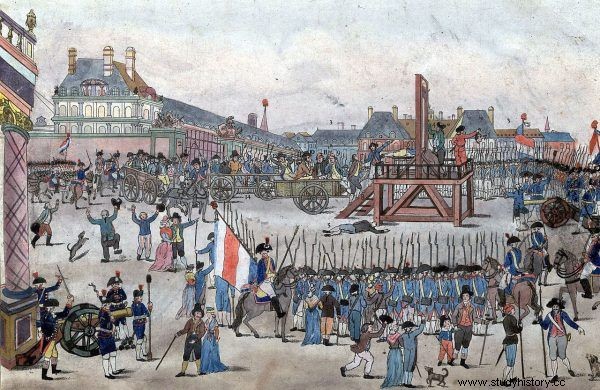

The guillotine was already in operation then continuously. It was not set up separately after each subsequent sentence, as before, but was left in Carrousel Square. And although it was moved several times more - to Revolution Square, then Bastille Square, Trône-Renversé Square and Revolution Square again - it was not dismantled anymore.

Guillotine on Revolution Square. Image by Pierre-Antoine Demacha (source:public domain)

Slowly and inexorably, the number of victims of the guillotine grew. New "records" were constantly being set. They became more and more impressive and frightening. On October 31, 1793, twenty-one Girondists were executed in thirty-eight minutes - reports Larson in "The History of the Beheaded Head Described". The devices, following the Paris example, began to appear also in the provinces.

Terror

However, the invention of Guillotin-Luois took the greatest toll during the Great Terror (1793-1794). Its use was perfected by Maximilian Robespierre, who led the Jacobins. In 1794 Nieprzekupny probably forgot that in the first months of the revolution he himself opted for the abolition of the death penalty .

A series of decrees of April and May 1794 significantly strengthened the revolutionary tribunal. On June 10, a decree was introduced to define the concept of "enemy of the people". From then on, the death penalty was punishable, among others, for such offenses as a desire to restore the monarchy or an attempt to block the Parisian provisioning.

In the first months of the revolution, Maksymilian Robespierre was in favor of abolishing the death penalty. But then he completely changed his mind on this issue (source:public domain).

Thanks to these legal "facilitations", the number of executions has increased significantly. According to French historian Julien Cain, 155 people were beheaded in Paris in April. In May - already 354. And in the next 46 days, until the fall of Robespierre - as many as 1376. Among the victims of the last months of Jacobin rule was Antoine Lavoisier, a prominent chemist, philosopher and economist. He was guillotined on May 8, 1794, along with 26 other convicts. The republic doesn't need sages or chemists - he heard when he asked for a postponement to complete the experiment he had started.

During this period, new daily records were also set. On June 17, 61 people were beheaded. Even more, 67 victims, were killed on 7 July. The official executioner of Paris also performed miracles in terms of the speed of executions. He did not remain unmoved, as Dr. Frances Larson emphasizes in his book:

On June 17, 1794, during one of the mass executions, more than fifty "conspirators" - including the shopkeeper, musician, and lemonade seller - were guillotined in 28 minutes - even the famous executioner Sanson showed a stir. Among the inmates was 18-year-old Nicole Bouchard, who seemed so thin and fragile to him that "even a wild beast would have mercy on her." Sanson was shaky; had to come down from the scaffold.

The famous chemist Antoine Lavoisier lost his head on the guillotine. Here, together with his wife, immortalized by Jacques-Louis David (source:public domain).

Paradoxically, however, as noted by the Polish expert of the period of the French Revolution, Bronisław Baczko, the largest "transport" of the Terror period was also the transport that ended the psychosis of fear . It included 71 people, beheaded on July 28 and 29, 1794. One of the first convicts was Robespierre himself. After this great closure, the new leaders gave the guillotine a rest. From then on it was used rather sporadically.

Balance sheet

What was the revolutionary balance sheet in the operation of a device that quickly - in just two years - turned from a symbol of modernity and humanitarianism into a tool of terror? The exact number is difficult to give, but we do have some approximations. Charles Sanson's grandson gives 2,918 executions of both sexes in the period from the fall of the Bastille, July 14, 1789, to the second year of the Directorate's rule.

The list ends on October 21, 1796. It applies only to the French capital, not taking into account data from the provinces; it also includes a number of convicts before the guillotine was introduced. For the entire country, Sanson gives an estimate of 13,800 executions.

The historian Réné Sédillot presents a more complete list. As she enumerates, the Paris victims of the "national razor" (as the device was affectionately called) were 2,639. However, it is impossible to present an equally precise number of victims of the guillotine in the whole of France. He estimates that there were approximately 17,000 executions during the Terror period. For the entire revolution, ie 1789-1799, he proposes the number 35,000.

Sédillot's global enumeration, however, takes into account not only the guillotine, but also lynchings, such as the September massacres of 1792, deaths of prisoners in custody, as well as executions carried out by other means. So the guillotine's casualties were probably significantly smaller. Louis-Marie Prudhomme, another revolutionary historian, gives the number 18,613 including 1,278 representatives of the nobility. To show the scale of the phenomenon, examples of statistics from the provinces are provided by Cain:

Between October 29 and the fall of Robespierre, 301 people were guillotined in Bordeaux; 332 victims were executed in two months in Orange; 120 were sentenced to death in twelve sessions of the Revolutionary Court in Marseille.

Why the guillotine?

Regardless of which of the proposed proposals is closer to the truth, it is obvious that the number of guillotines is only a drop in the sea of victims of the French Revolution. The Vendée civil war alone resulted in the deaths of around 400,000 deaths on both sides, Sédillot estimates. Other estimates range from 100,000 to even 600,000! During all the wars of the revolution and the empire, even two million people died ...

As to exactly how many people were guillotined during the French Revolution, discussions are still ongoing. However, it was at least a dozen or so thousand unfortunates. The picture shows the execution of Robespierre (source:public domain).

Yet it is the guillotine that remains an inseparable symbol of the revolution. For our fathers, the Revolution is the greatest product of the genius of the congregation (...). For our mothers, Revolution is a guillotine - Victor Hugo wrote in 1820. Contemporary researcher Daniel Arasse also emphasizes that linking the revolution with the image of the guillotine is one of the most widespread stereotypes.

In fact, the machine that took the name of Dr. Guillotin and his family embodies both the revolutionary hopes and the terror they entailed like nothing else. It shows how dreams of progress degenerate into abuses of power; that power which was supposed to bring liberation to the people. And all that is left for him is to compose litanies to the "holy guillotine" and shout: Holy guillotine, defender of patriots, pray for us (...). Magnificent machine, have mercy on us.

Buy the book with a discount at Empik.com: