Hunger was an inseparable element of the camp existence. He devastated the body and psyche, pushed many to the brink of desperation. For those prisoners who managed to survive, there was nothing bizarre, hideous, or unacceptable enough to not be included in the menu.

In "The Last Prisoner" - an extraordinary novel by Nina Majewska-Brown, depicting the fate of two generations associated with the Auschwitz camp, we read:

Death lurks everywhere, any time of the day or night. During roll call and at work, when the Germans hand out food and when they get bored. Besides, under these conditions, they do not have to help us move to the other world. Grim Reaper tirelessly circulates between us, putting his cold, bony hand on our foreheads. [...] We die of starvation, because the served portions will not feed anyone, not even a small child. We die as a result of backbreaking work, which we are unable to bear.

The heroes of the book, the parents of the title "The Last Prisoner", survived the hell of the camps not unscathed in body and soul. Avoiding starvation was part of the struggle to survive against the powerful machine of Nazi genocide.

Water in the sausage and fecal bacteria in the meat

On December 10, 1947, a trial was held before the Supreme National Tribunal in the framework of the so-called The First Auschwitz Trial, which took place in Krakow from November 24 to December 22, 1947. Former members of the staff of the German concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau were among the accused in this trial. On that day, prof. Jan Olbrycht, former prisoner:

When it comes to feeding the prisoners, it is from the authentic German documents, and above all the books of the Institute of Hygiene in Rajsko [...] that the food distributed to the prisoners of the concentration camp in Oświęcim did not meet the most primitive requirements in terms of quality or quantity nutrition .

Contrary to the regulations of the camp, the prisoners received meals with too low calories, in addition with poor nutrition and in small rations. The meat, if it ended up in the camp kitchen at all, was rotten and contaminated with fecal bacteria.

Prof. Olbrycht calculated that the pate served to prisoners contained 47.9% to 71.3% of the water content and from 14.3% to 18.6% of the protein content, and 51-73.2% of water and 12.2-23% in black pudding. 8% protein. In the camp kitchen, soups were cooked using the lowest quality animal waste, "increasing" the nutritional value by adding moldy bread or products confiscated from prisoners from new transports.

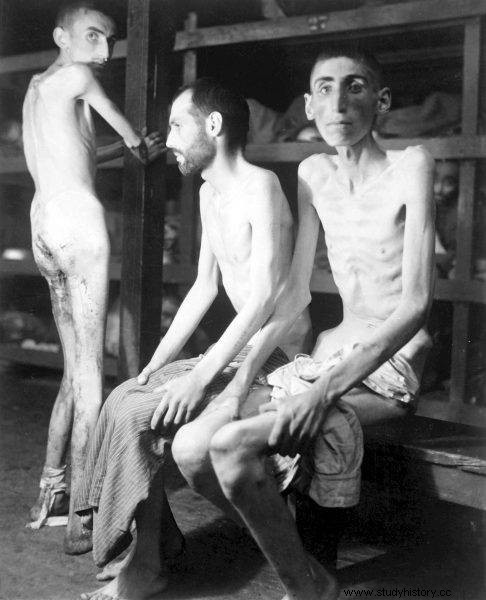

Extremely emaciated prisoners of the Buchenwald camp

This practice was described by Miklos Nyiszli, a forensic specialist and an Auschwitz prisoner, who was "promoted" to the assistant of the infamous doctor Mengele:kinds of salami, biscuits and chocolate. ”

It was little consolation that the sick were fed differently:oatmeal gruel (about 330 liters were cooked daily for the needs of the hospital, which was not enough even for some of the sick), and salt was not added to the luric soup. Stanisława Leszczyńska in the "Report of a midwife from Oświęcim" wrote:" The main food of the patients was rotten overcooked weed, containing without exaggeration about 20% of rat faeces ”.

Extreme nutrient deficiencies emerged quickly as a result of hard work and hunger, usually over a period of three months turning into the so-called hunger sickness. This was consistent with the statement repeated many times by the SS, according to which a decent prisoner will survive at most 3 months, and if he survives longer - he is a thief. Food rations were strictly defined and segregated so that no inmate was given more than was necessary to keep them on the verge of death.

In bread - mold with sawdust

Meals for prisoners were prepared in the camp kitchen with products from a utility warehouse, regularly robbed by the staff. Food was distributed by prisoners and female functionaries - unless they had appropriated it beforehand. The very distribution of meals can hardly be called orderly or fair, as mentioned by former Auschwitz prisoner Euzebiusz Bogacki:

Whether he had a special assignment or organized bread for us himself, he distributed to everyone according to his conscience, thinking that he was very fair, and he did it like this: we were parading naked, in front of him, he watched closely and to those who looked so thin that nothing would help him, he would not give this bread , He did not give "fat people" either, only those that, in his opinion, promised hope for improvement, he received a portion of bread for refreshment.

It was the bread, often moldy, that was the basis of food in the camp. It was served for breakfast and dinner, sometimes with beetroot marmalade, margarine or the already mentioned worthless and poisonous sausage. Bread was a thing that was fought for life and was valued and its consumption was celebrated. An insurgent and a former prisoner of Auschwitz, Bogdan Bartnikowski, recalled the celebration of a poor meal:“I will have bread in my mouth soon! I will chew slowly, slowly until it turns into a thin mush, then I swallow it and finally for a moment I will not feel that furious tugging and burning in my stomach. "

The text was created, among others based on the book by Nina Majewska Brown "The Last Prisoner of Auschwitz", which has just been released by the Bellona publishing house.

The bread was also served with a thin dinner soup, cooked from root or leafy vegetables, often rotten, sometimes with a bit of groats. Not everyone was given a bowl, and it happened that for some there was neither a portion nor time to eat. "Coffee in the morning, coffee in the evening, and a little Ava for dinner" - that's how the diet in the camp nursery rhyme summed up, and Avo referred to a powder added to soup, a food extract, which some say is ground bone or saltpetre.

Nevertheless, the hungry prisoners took every opportunity to eat her fill, and these were extremely rare. In the memoirs of Adolf Gawalewicz we read about such a case:

One summer Sunday, out of breath, Stańda lets me into the side hall of block 15. There is an almost full 10-liter cauldron of the camp's rare potato soup:"Eat fast, I am on the verge of cheating." There is no time to look for a bowl, spoon, etc. tools. I eagerly scoop the mushy, delicious soup with my cap and lick this special nectar. I must have had eight liters of soup in a matter of minutes. Full, overflowing, splashing and happy, I lie down on the gravel of the roll call square - the orchestra is playing the Sunday concert.

The camp dinner also consisted of bread - dark, clayey and most often moldy, with sawdust, and with a bit of luck also a bit of margarine (20-25 g) or a tablespoon of beet marmalade, horse sausage, possibly pate or black pudding.

Eating dinner was a ritual in the camp, as Stanisław Grzesiuk, a former prisoner of Dachau and Mauthausen-Gusen, mentions:“ Dinner was eaten in silence and anointing. ... . The idea was not to lose the slightest crumb. After eating the bread, crumbs collected in the center of the napkin. There were very few of them, but everyone thought they would suffer a great loss if the crumbs fell to the floor and they could not be lifted. "

Twice a week, hard-working prisoners received the so-called "Culaga" ( Schwerarbeiterzulage ) in the form of bread with brawn or sausage. Herbal "tea" and bitter luric acorn coffee were served with all meals.

Treasures in packages, and in dreams - mountains of sugar

According to the regulations of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, food parcels were forbidden because prisoners could buy food in the camp canteen with German marks deposited on the day of the party or sent by their relatives. In fact, few people could use the canteen, where - apart from letterforms and stamps, cigarettes and hygiene products - little was available.

When in the fall of 1942 the SS authorities lifted the ban on sending food parcels (excluding Jews and Soviet prisoners of war), the situation slightly improved. products, but also lighter work . This is how a former prisoner, Maria Elżbieta Jezierska, describes this "secondary market":

Former supporters of swapping bread for sausage […]. There were also supporters of replacing onion packages with bread. I give approximate prices in Brzezinka:a portion of culagowa, red sausage =a portion of bread, a large onion =a portion of bread, 5-6 raw potatoes =a portion of bread, for cooking a potato soup - a portion for cooking or a portion of bread, a large onion, a piece of bacon; a large piece of bread =a large slice of bacon or, for example, a sweater; bread ration =shirt etc.

Survival in the camp depended, among others, on from the kindness of fellow inmates who shared even the smallest crumbs of bread (in the photo:Auschwitz prisoners).

In this way, food and other necessary products were "organized". Until August 1944, the International Red Cross also sent parcels to prisoners, using personal data provided by the camp's Resistance Movement, then everything was confiscated.

"The belief that one of my relatives is alive sprouts in me only when I receive one kilogram food parcels through the Polish Red Cross," we read in "The Last Prisoner" . - " There are only valuable things in them:onions, sometimes garlic, bread, once there was even a small bag with sweet sugar crystals. I gently drool my fingertip and savor its taste as if I had been served the most delicious cake. Another prisoner, this time from Ravensbrück, Zofia Mączka-Patkaniowska, saw sugar only in hallucinations:

On the sixth day of hunger, cold, darkness, and loneliness, I started seeing things. I saw wonderful crystal sugar mountains. I was eating those sugar mountains and my hunger seemed to diminish. Whirling circles of light appeared on the wall and the sugar mountains returned again.

Sugar may have been a dream come true, but there have been occasions when the camp diet has included completely unexpected delicacies, such as ice cream or cake. In one of the reports from Auschwitz, we read about eating the first ones on the occasion of the Allied invasion in Normandy or about preparing a peanut cake as a gift for a girl from secretly obtained ingredients, as described by former Auschwitz prisoner Julian Kiwała:

( obligated Col. Felek Włodarski (confectioner by profession) to make a nut cake.This cake, decorated with roses with spikes - symbolizing the love afflictions of Leon - was to be delivered by us to one prisoner temporarily staying in Block 10 in Oświęcim. At the moment when we admired the artistic execution of the decoration, for which even prontosil injections, methyl blue tablets and other chemical reagents were used Suddenly, Dr. Rohde entered the Lagerarzt SS kitchen through the half-closed door. "Who is this cake for?" He asked. Then Zdzisław Buchner replied most calmly - "For you".

Lime potatoes are worth their weight in gold

The hungry prisoners did not dream of delicacies every day - they only thought about how to fill empty bellies, showing great creativity in inventing dishes from seemingly inedible or mismatched ingredients. The delicacy could be a slice of raw potato with a saccharin leaf, which undoubtedly harmed, or a boiled potato stolen from the kitchen, divided among numerous companions of misery, as we read about in "The Last Prisoner":

Sophie, who works in the kitchen and who has just managed to bring one small potato, breaks it meticulously into three parts and serves it with solemnity, as if she was offering us a precious treasure. […] It is so good, slightly sweet, tasty, no matter what. I would eat a whole bowl of them, preferably with onion and fried, smoked bacon. Tears run down my cheeks by remembering how I complained at the table that my mother served us the same for dinner twice in a row.

photo:USHMM / public domain In the camps, hunger killed as much as hard work and Zyklon B.

The alternative, as long as the conditions were found, were potatoes baked in… lime. In order to avoid treacherous smoke, a bucket was buried in the ground, in which potatoes were then placed in layers, covered with ungraded lime, poured over with water and covered with soil. A few hours later, there was a "feast" . Potatoes could also be used to make pancakes, as described by Wiesław Kielar in "Anus mundi":

I often went to leichenhal for chat [i.e. trupiarni - ed. aut.] . Gienek Obojski was picking up raw potatoes from somewhere. There was a coke oven in the basement. We baked potato pancakes on a baking tray. We then sat on the "coffins" around the hot stove, the cakes sizzled, their pleasant smell pleasantly irritated the nostrils, killing the stench of chloride that covered the corpses stored here. […] There was a nice atmosphere, like at a scout campfire.

Potato pancakes seemed to be an unusual delicacy - but not like real meat stews. And it didn't matter that the meat came from a dubious source. Many testimonies have survived that the prisoners ate dogs. In Kielar's account, for example, we read:“Then one of the installers suddenly started barking, growling, playing with a bone, imitating a dog. After a while, we all pretended to be barking dogs. The SS men were initially amused by this wild game. However, they knew enough Polish to understand the words about the tragedy of Dreschlerka's dog amidst this barking and laughter. […] Soon they left the block, being said goodbye to a happy dog haukania ”.

Anna Odi (on the left) with the author of the book "The Last Auschwitz Prisoner" Nina Majewska Brown

The protagonists of "The Last Prisoner", the parents of Anna, who lives in Auschwitz to this day and works in the museum archives, clung to almost any way to stay alive in the hope of ending the war or escaping the torturers.

After the war, they started a new life, but the camp traumas were deep in their minds. In an interview with the author of the book, Anna mentions that they made sure that the home would never run out of food, and at the same time not to waste it, which was unimaginable for them. During family meals, there was a place for everyone at the table, food was shared with neighbors or local children. It was certainly remembered that in the hell of the camp, survival often depended on those who managed to remain human and did not leave others to their fate.

The text was created, among others based on the book by Nina Majewska Brown "The Last Auschwitz Prisoner", which has just been released by Bellona.

Other literature:

- Bartnikowski, B., Childhood in striped uniforms, Oświęcim 2016.

- Bogacki, E., Camp notebook , Pruszków 2019.

- Cebo, L., Women prisoners in the Nazi camp in Oświęcim-Brzezinka , Katowice 1984.

- Ciesielska, M., Camp hospital for women in KL Auschwitz-Birkenau (1942-45) , Warsaw 2015.

- Kielar, W., Anus Mundi , Krakow 1976.

- Kiwała, J., Diet kitchen (Dietkuche) in the hospital of the concentration camp in Oświęcim , "Przegląd Lekarski", 1964, No. 1a.

- Klee, E., Auschwitz, Third Reich medicine and its victims , trans. E. Kalinowska-Styczeń, Krakow 2001.

- Leszczyńska, S., No, never! It is forbidden to kill children , Warsaw 1991.

- Nyiszli, M. "I was Dr. Mengele's assistant" , trans. Tadeusz Olszański, Oświęcim 2000.

- Olbrycht, J., Health issues in the Auschwitz camp , [in:] Occupation and medicine. A selection of articles from Przegląd Lekarski Oświęcim, 1961–1970 , Warsaw 1971.

- Rees, L., Nazis and "The Final Solution" , crowd. P. Stachura, Warsaw 2005.

- Ryn, Z., Kłodziński, S., Psychopathology of hunger in a concentration camp , "Przegląd Lekarski - Oświęcim", 1985; 25 (1):48.

- Snoch, J., A feast in the abyss. A few remarks on the culinary habits of prisoners of Nazi concentration camps [in:] "The Peculiarity of Man", Toruń-Kielce 2017, No. 1.