Operation "Cart" - stealing the German mail going to Gdańsk and Królewiec - was in the 1930s one of the most spectacular successes of Division II of the Border Guard. It was thanks to her that most of the information about the German army was gathered. But did the Germans really suspect nothing? Or maybe they just disinformed the Poles?

The head of the Branch No. 3 Branch II, captain Jan Henryk Żychoń, liked unconventional actions, sometimes even… illegal. For him, the results counted, and he had no qualms about the intelligence fight against the Germans. When in 1930 he took over the management of the Bydgoszcz branch of Polish intelligence, whose work was focused on the most important regions of East Prussia, Pomerania, Gdańsk and even Berlin, he came up with the idea to break into German transit trains, although according to international agreements they had the right to pass through Polish territory.

The idea was not entirely new. It is known that already in the mid-1920s, the Krakow branch of Branch II intercepted mail addressed to the German consulate in Katowice . Interestingly, Żychoń was working there at that time. It is not entirely clear whether he was the initiator of the action, but he was definitely present during its development. Back then, e-mail interception was called "ticketing".

Contrary to international agreements

In 1930, Żychoń initiated the action "Aunt" in Pomerania. He gave the appropriate orders and ordered a group to be organized that would take over German letters on the trains. They traveled several routes, incl. through Tczew, Chojnice and Wejherowo. There were many types of trains running there - and for each of them a different technique had to be devised.

Passenger and express trains with postal wagons at the border received a Polish locomotive and a conductor's crew, but German postal officers traveled in Deutsche Reichspost wagons. A special contract also provided for the carriage of passengers without the need for passport control.

It was different with freight trains, which sometimes transported military equipment and even soldiers. The Weimar Republic was entitled to a certain number of such shipments - in sealed wagons. According to international agreements, soldiers had to deposit their weapons in a designated place and were not allowed to leave the warehouse.

The transport of mail was also regulated by other agreements. The countries belonging to the Universal Postal Union guaranteed fairness in the delivery of transit shipments. And the Second Polish Republic was one of them.

Captain Jan Żychoń, it was he who gave the green light to the Operation "Cart".

The aforementioned agreements made it easier for the Germans to transport them through Polish territory, and at the same time opened up many possibilities for the successful Żychoń. However, the plan of sneaking into the carriages with German parcels was risky - in the event of a mishap, Warsaw would be rightly criticized. Certainly no one wanted that.

Read also:Hunting for Captain Żychoń. How did the Germans try to get rid of the Polish intelligence ace?

Vodka and geese in the service of Division II

It's one thing to have an idea, and the other is to make it come true. The development of the action took several months. First of all, it was necessary to recruit Polish railwaymen and postal workers. They were to make friends with German officers. The agents of Division II, now called postal martens, took geese, chickens, ducks or butter "for which German officials were very fawning" - as Witold Langenfeld, one of Żychoń's subordinates later described. And he added: "It was not uncommon for German colleagues to treat their German colleagues with» Polish pure vodka «while driving.

The Poles entertained the Germans with a conversation, and when the train was approaching the border, in order to make up the time, they asked them for help in sorting the mail. It was then that the "martens" could pick up valuable parcels - they were sent to the 2nd Division officer traveling on the same train who photographed the correspondence, and then restored the parcel to its original state. The reviewed letters and parcels returned to the mail car, but in the next train. Poles knew that the Germans only numbered the bags with parcels, so they would not know if an unchecked letter arrives a few hours later.

In case Polish postal workers were found stealing envelopes, Żychoń recommended that caught agents testify that they were looking for letters with money. Otherwise, they faced a penalty for espionage, and "only" for theft. “ We most often thus took over correspondence between German shipyards and the admiralty regarding shipbuilding, or correspondence between shipyards or other factories of the war industry. Such correspondence was of great value to the intelligence service. Sometimes we also got into our hands this expensive military mail "- recalled Major Janusz Rowiński, one of the people of Żychoń, who supervised the operation while still a captain.

From time to time, the Germans improved the way of protecting parcels. At the beginning of 1931, Reichswer began sending all her letters registered and sealed. It took more time to open and close them without a trace. Another time, on the Strzebielino-Malbork route, Poles encountered sealed bags - this interrupted the operation for about half a year, until, thanks to cooperation with the post office in Chojnice, German seals were obtained.

Microlamps, scalpels, plaster

However, it was not limited only to theft of mail during events with Germany. Sometimes the carriages were simply broken into. This was the responsibility of the agents - "aunties". The action itself was as follows - after crossing the Polish border, when there were no more German railwaymen on the train, the engineer cooperating with the 2nd Division slowed down the gear. At that moment, "aunties" appeared, who, after entering the carriages, looked at their contents. At times, the part of the mail interesting for the intelligence service was simply… thrown outside.

During the journey through the Polish section, which was just over a hundred kilometers long, the seals had to be broken, what was needed to be stolen and the parcels resealed. It required the efficient coordination of many factors . The Żychoń did not hesitate to hire thieves - they were the best ones to break in and steal without leaving any traces. It was also necessary to have a good command of German and knowledge of the German army. Historian prof. Wojciech Leather writes:

After breaking into the carriages, it was possible to make photocopies of more important documents or even to keep packages of correspondence and toss them into bags on the next train. Military equipment, carried in large numbers, such as gas masks, uniforms, optical equipment or pieces of armament, could simply be stolen.

"In this way, among other things, German air rifle, cannonballs, pieces of German soldier's equipment, and even the luggage of soldiers leaving or returning from military courses, in which luggage often there were very valuable notes and notes from these courses "- said Rowiński.

The biggest problem was the seals. But a way was found - they learned to counterfeit them. In the documents of the Bydgoszcz branch, you can find Żychoń's request to the Head of Division II for the equipment needed for the work of "aunties":complete wash bottles, electric heaters 220 v, micro-burners, scalpels, impression plaster, porous porcelain, rubber gloves and even oil, alcohol, cotton wool and acetone .

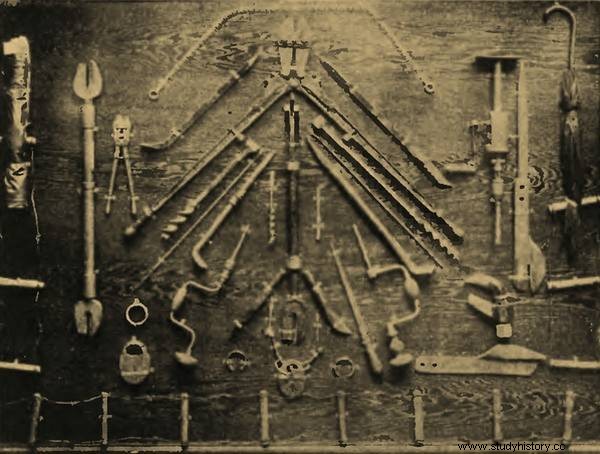

Without the help of the cashiers, the "Cart" operation would have failed. The photo from the late 1930s shows the tools used by adepts of this "trade"

Even before the operation began, thorough research was carried out on how the warehouses are sealed. Division II sent his men to Germany to buy strings, wires and padlocks that were used by the local post office. All this in order to be able to open the wagons, shake them and close them in a way that would not arouse suspicions. "The technique of our work, both in the wagon and when using the correspondence itself, was very careful and did not leave any traces" - recalled Rowiński.

The work of people in Żychonia ran smoothly. In 1936, in order to avoid the risk of exposure, the name of the action was changed from "Aunt" to "Cart "- too many people have heard this code name and apparently even in the corridors of the General Staff one could hear conversations about" aunt ". In the second half of the 1930s, the operation brought in as much as 60 percent of all materials that flowed into Division II on Germany.

Read also:The best intelligence agents in pre-war Poland

Mysterious "ice houses"

In 1937, Captain Rowiński noticed that "the sets of freight-fast trains include special ice-house wagons, with double walls, complex double locks, sealed with postage and customs seals, marked with stickers with the word" post "". Rowiński and Żychoń decided to visit them. They were given the green light and in August this year Rowiński started preparations that lasted over three months. It was necessary to counterfeit keys, sealers and material for seals. It was all the more difficult because the Germans did not use ordinary lead in these seals, which was commonly used, but a special alloy.

Rowiński obtained the original seals thanks to agents who worked in German postal cars. The technical department in Warsaw was thus able to obtain the right alloy. Taking transit trains several times a week, Rowiński matched the keys. In 1938, as Witold Langenfeld reported, the Germans stopped using standard and widely available padlocks. In Rowiński's opinion, these new ones were extremely precise. Eventually, a specialist sent from the capital helped to forge the keys. The new operation, this time codenamed "Janusz", was to start bringing even more information soon.

Usually, the action was as follows:Rowiński jumped on the train outside the station - at the agreed place, the driver slowed down (only on exceptionally dark nights he would still go inside at the station in Tczew or in Chojnice). In the wagon, he looked through the mail and took what at first glance might have some value. He had a lot of time - about four or five hours. Then the privy driver slowed down again, Rowiński threw out the sorted consignments and jumped out himself after them.

A car was waiting for him by the tracks, which he used to drive to Chojnice. There, envelopes were opened and their contents were photographed and then sealed. Sometimes the wax seals also had to be forged.

German negligence

They were "fired" not only on trains. The warehouses to East Prussia from Gdańsk and the Reich passed through the train station in Tczew. The post office was waiting in sealed bags for a warehouse from Germany, which arrived several dozen minutes later. Recruited in 1935, the head of the post office took the bags to his office, where the agents of the Two went to work. Afterwards, unsuspected bags were put back in their place.

The "Aunt" and then the "Cart" were used not only to steal mail, but also to ... plant it in order to maintain correspondence with Polish agents in the Reich. The "post marten" put the letters into bags - these were sent to the addressees as sent from the territory of Germany, thanks to which non-German censors did not pay attention to them. They were interested in letters coming from abroad. In total, the costs of the action were around PLN 1,000 per month . It was the equivalent of two or three good salaries - ridiculously little for the most important source of knowledge about the German army.

In the 1920s, Gdańsk was a city full of spies (photo:public domain)

It all looked beautiful. But isn't it too beautiful? This question was already asked by the officers of Division II. Janusz Rowiński concluded that the Germans must have noticed that the equipment was missing. However, if the seals looked intact, they probably assumed that he might have disappeared during loading, still in Germany. "Never, until the outbreak of the war, there were any suspicions that the equipment could be lost from transit trains" - assured Witold Langenfeld. He had evidence of this in the form of intercepted and decoded German radio messages. “The manager of one office reproached the head of the other office. He blamed one another for the missing item. ”

It is possible that the Germans assumed in advance that their mail was being stolen, but they did not attach much importance to it. Ultimately, only regular mail was sent in this way - i.e. through transit through Polish territory. Although it was also possible to extract important information from it. In such situations, regularity is the key. For example, the carefully followed innocent correspondence between shipyards regarding the procurement of equipment and materials made it possible to determine the scale of the Kriegsmarine expansion. A lot - even about the size of the army - can also be told by inconspicuous documents related to food supplies.

It happened, however, that there was a special shipment. Generally it was because of human error, against which even German accuracy could not protect. And so once a secret document was sent to Konigsberg by mistake instead of to Dresden. And from Konigsberg - through evident carelessness - he had already been returned by normal transit. Rowiński believed that the carelessness resulted from the enormous pace of expansion of the German army. The administration just failed at times.

Historian Marcin Przegiętka described a German instruction from 1936 regarding the transport of parcels, from which it could be concluded that the Germans suspected that their mail was being viewed, but this concerned:"only parcels sent in ordinary civil transit trains, without their own escort, not military transit trains carrying German soldiers or escorts. ”

In his book Operation Reichswehr, Marian Zacharski presents a German document from 1935, which shows that during the years of "Aunt's" operation, the Germans assumed that Poles did not pick up mail, as it would be inconsistent with the honor of postal workers. And when they became suspicious that the post office on the Breslau-East Prussia route was being stolen, they made a detailed expert opinion on the seals. The conclusion was unequivocal:"The letters were probably taken out, photographed and put back in the bag the next day" . Interestingly, the counterfeit seals were said to be even better than the original ones.

How about inspiration?

The document that Zacharski reached sheds new light on what the Germans knew at the time. However, it should be remembered that Poles already guessed that their opponents suspected them. In 1938 or 1939, an instruction fell into Polish hands which forbade the sending of secret and important military mail through the Second Polish Republic. Nevertheless, military parcels - including the secret ones - continued to travel on trains in large numbers.

Moreover, the document published by Zacharski would suggest that if the Germans did become suspicious, it was only in 1935 - five years after the start of the operation. But more importantly, the mail sent from Breslau to East Prussia was of secondary importance - and only this route was covered by the letter. Anyway, as Marcin Przegiętka writes:"we do not know whether this letter was handed over to the military authorities, let alone whether it was sent to the Abwehr".

The most important argument is the fact that the Germans did not make an international scandal regarding the theft of mail - and thus the violation of the extraterritoriality of trains - and did not use it for propaganda against Poland. And they used to do it:the German press did not pass up any opportunity to prove the Second Polish Republic's bad intentions or failure to respect international agreements.

Moreover, as Rowiński rightly observes:“If the Germans suspected that we were getting into their closed carriages, they would first use special precautions, such as new locks or other new seals. I find that I did not notice any such precautions on the part of the Germans. Although the seals were changed, it happened periodically and it was normal. ”

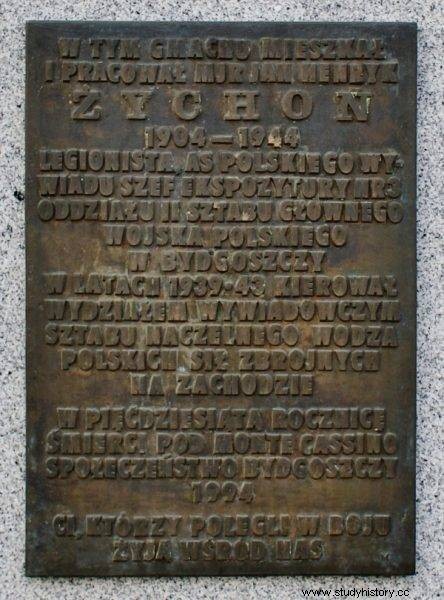

Plaque dedicated to Jan Żychoń in Bydgoszcz

Or maybe the Germans knew about everything, but did not make a scandal, because they used the mail to misinform the enemy? If this was the case, then not earlier than 1935. Only that the Poles stole the correspondence at random - the Germans could never be sure which day, which wagon and which bag would be plundered. So they would have to continuously produce enormous amounts of credible-looking fake mail. In theory it is possible, in practice probably impossible.

“Inspiration in this way, with the relatively large amount and variety of material and the casual nature of our control, would be technically extremely difficult. Moreover, as we stated, the material we took over was absolutely authentic "- commented in 1942 Janusz Rowiński, already a major . Żychoń assessed the obtained materials as "valuable and, most importantly, 100% certain". It is possible that the certainty of Żychoń was exaggerated, but at the moment it can be said that - despite the doubts - the "Cart" operation was the greatest success of the Bydgoszcz branch.