It is said that the work of cryptologists shortened World War II by up to two years and saved thousands of lives. Army and naval radio intelligence was reportedly one of the best of its kind in American history. But why don't we remember that he mostly employed women?

About 11,000 women in America were employed to break codes during World War II. It was more than half of the 20,000-strong corps of workers working on secret codes. Ladies had a huge, almost 70% advantage in the cryptanalytical services organized by the army. They also accounted for over 80% of the personnel of domestic navy-maintained units of this type.

Moreover, as it turned out, the results obtained by the American women exceeded the wildest expectations of their commanders. Initially, it was planned to entrust them only with simple but tedious tasks, requiring diligence and accuracy, but not "genius" (appearing only in men!). Meanwhile, it was they who made many breakthroughs in reading messages sent by the enemy. "Their work was of enormous military and strategic importance" - emphasizes Liza Mundy, an American journalist who described the contribution of women to cryptological operations in the book "Cipher Girls. They helped win the Second World War. " And he is right.

"Crazy Profession"

"If America had any cryptanalytic operations at all before World War II, it was largely thanks to a small group of prominent women," says Mundy. "Unlike many of the jobs women did during the war, cryptology has never been a traditionally male occupation," echoes her historian Jennifer Wilcox.

William F. Friedman and Elizebeth Smith Friedman (photo:public domain)

Indeed, American women took advantage of the fact that men were not particularly interested in breaking secret codes. Already during the First World War, when the first permanent cipher offices were established, the gentlemen preferred to operate at the front, believing - rightly so - that it would be more useful for their careers. After the end of the conflict, cryptology itself was not held in high esteem in the United States. "It was perceived as a secret, and even a bit crazy profession, treated more like a hobby or an amateur occupation" - admits the author of the book "Cipher Girls".

Under these conditions, the star of "America's first cryptanalyst," Elizebeth Smith Friedman, could shine. She began her career at Riverbank under the tutelage of Elizabeth Wells Gallup, who tried to prove that ... the true author of Shakespeare's plays was Sir Francis Bacon. The unit, which deciphered secret messages supposedly contained in English dramas, soon became the only code-breaking facility in the US.

Friedman and her husband (whom she met at Riverbank) joined the Washington War Department after a few years. Later, she independently organized an efficient cryptanalytical service in the Coast Guard. She headed it until World War II, when the unit was incorporated into the navy, and Elizebeth - as a woman - was taken from command.

Which does not mean that the pioneer of American cryptology has abandoned the office she created. On the contrary, she worked in it throughout the war. Its achievements remain top secret to this day. We know, however, that the unit - renamed OP-20-GU in 1943 - worked, among other things, on deciphering Enigma .

"One of the Coast Guard's greatest military successes was breaking the Enigma code used by the Abwehr," reports (perhaps a bit too optimistically) specialist in the history of cryptology, John F. Dooley. In fact, the unit was able to read a large proportion of the enemy's messages, including with the commercial version of the machine in its possession. She also unraveled the cipher used by a secret broadcasting station in Argentina. All this would not have been possible without Mrs. Friedman - without her there would be no OP-20-GU!

"Any cipher made by a man can be cracked by a woman"

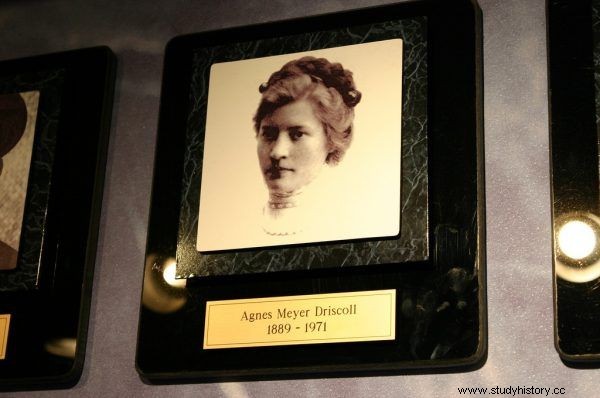

At the same time as Friedman, another legendary figure of cryptanalysis, Agnes Meyer Driscoll, entered the world of intricate codes. From 1918 she worked for the American Navy. She quickly found herself in the ciphers and communications section, where she was involved in creating secret messages and ... testing "madmen's inventions". It was about machines presented as excellent encryption tools. As you can imagine, most of them were easily seen by the woman.

With time, "Miss Aggie", as the eminent cryptologist was called, began to be entrusted with more and more key tasks. In the 1930s, it contributed, among other things, to deciphering the messages of the Japanese navy intercepted by the navy. "Mrs. Driscoll was responsible for the initial solution and much of the cracking of the new ciphers," admitted Cipher and Communications chief Joe Rochefort. Others described her contribution to the work on enemy codes as "spectacular." As Liza Mundy writes in her book "Cipher Girls":

Her performance had huge real-world ramifications. Thanks to the achievements of Driscoll, the Americans learned in 1936 that the Japanese had perfected their warship so that it was able to reach speeds of over 26 knots.

The United States did not have such a fast ship, so the Navy created a new class of ships that could exceed that speed. It was a major intelligence achievement - and one that justified all the expenses related to the establishment and existence of a research section.

Photo by Agnes Meyer Driscoll taken at the US National Cryptologic Museum (photo:Ryan Somma, CC BY 2.0 license)

During the war, Driscoll also worked on Russian systems. After all, as she claimed, "any cipher made by a man can be broken by a woman"! In the meantime, she trained the next generation of American cryptanalysts. Her "hand" in the secret services of the US Navy was visible long after she left the Navy in 1949. No wonder that the head of naval intelligence Edwin Layton admitted: "She was unmatched in the field of cryptanalysis" .

"Gene found what we were looking for!"

In the 1930s, Signal Intelligent Service, a unit subordinate to the US Army, also dealt with decoding Japanese messages. Interestingly, it was headed by Elizebeth Friedman's husband, William.

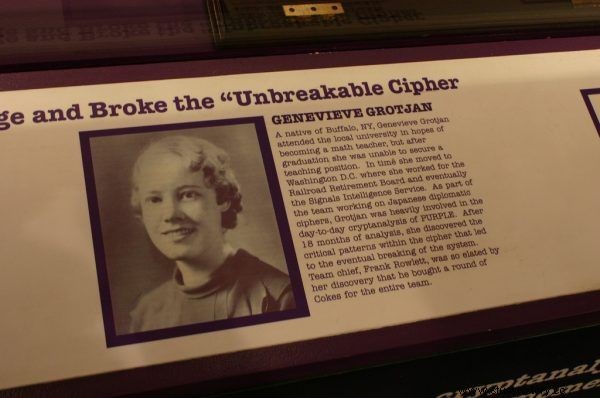

The focus of the cryptanalysts stationed at Arlington Hall is two machines from the Land of the Rising Sun, known as "red" and "purple" (also known as the Japanese Enigma). The first ciphers, transmitted by the much more complicated "Purple", were intercepted in February 1939.

Fortunately for the Americans, the breakthrough in the work on breaking the code of the new device took place in September 1940, so before the US entered the war. All thanks to another woman - Genevieve Grotjan, who was the first to discover the pattern in the so far elusive sequence of characters. When she shyly informed her colleagues about it, they were almost euphoric. "Gene found what we were looking for!" One of them shouted.

Analysts working at the heart of American cryptography - Arlington Hall circa 1943 (photo:public domain)

Genevieve's work was also appreciated by its boss, William Friedman. He later considered breaking the purple code as "by far the most difficult cryptanalytical problem successfully solved by any intelligence organization in the world."

"It's really a lot of water and you don't see that many people on it at all"

There were many more women like Elizebeth, Agnes, and Genevieve. In 1943, Flobeth Ehninger was instrumental in solving the SAUDI cipher, for example. At the same time, Wilma Berryman made the first breach at Arlington Hall in breaking the Japanese Army's coding system. In turn, Delia Taylor Sinkov, thanks to her phenomenal memory, helped to review the cipher of the administration from the Land of the Rising Sun. And that's not all! After all, almost every day more talented decipherers joined the American cryptanalytical services ...

Unfortunately, although the commanders of the army and later cryptologists looked at the achievements of their colleagues with admiration, their contribution to the war effort did not receive adequate recognition. "Both the recruitment of these American women and the fact that they were the ones behind some of the most important successes in cryptanalysis were one of the best kept secrets of that war," writes Liza Mundy.

Commemorating Genevieve Grotjan in the American National Cryptologic Museum (photo:Ryan Somma, CC BY 2.0 license)

Lord with praise was easy to overlook. After all, they were recruited as labor for tasks that required "tedious labor." As the American journalist reports:"it was considered their domain - diligent, repetitive work at the initial stage of activities, so that men could take it over when it became more interesting and difficult". No wonder that back in the time of the global conflict, Rear Admiral Joseph R. Redman found it appropriate to explain to decipherers ... how big the ocean is . "It's really a lot of water and you don't see so many people on it," he argued.

As a result, even the history of cryptography and cryptanalysis often lacks broader references to women. When Hervie Haufler, who studies the subject, postulated that cryptanalysts made a greater contribution to winning the war than Dwight Eisenhower or Bernard Montgomery, for example, he gave all honors to men. Among the names of "war heroes" he mentioned, not a single woman appeared!

What do you say, ladies? Well, they worked and they keep working. "Many women in cryptography, especially Grace Hopper of WAVES, learned during the war the systems that helped create computer languages - and changed the world," said Doris Weatherford, a female researcher. American during World War II. Other women of the fair sex have dedicated themselves to the development of radio-intelligence or cyber security ... In the end, they proved that nothing is impossible for them.