In 1897, the Belgica ship set out on a scientific research expedition to Antarctica. Today, the experience of his crew is useful in ... planning space missions.

In the nineteenth century, literature and poetry were full of descriptions of doomed polar expeditions and the horror awaiting the daredevils who dare to venture into hitherto unexplored regions. In 1841 in the novel In bezdni Maelströmu Edgar Allan Poe painted the destructive power of the element, bringing death and madness. Certainly not such experiences were expected by the Belgian crew, which consisted of nine Belgians, six Norwegians, two Poles, a Romanian and an American .

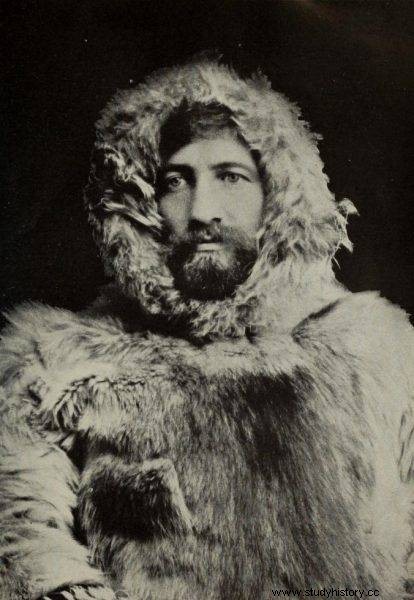

The mission was called the Belgian Antarctic Expedition due to the fact that the organizer and commandant was Baron Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery, an officer of the Belgian Royal Navy . Frederick Albert Cook, 32, was the expedition's doctor and photographer. Roald Amundsen, 25, the future South Pole Conqueror, served as a second mate on the ship . 25-year-old Antoni Bolesław Dobrowolski, who escaped from exile in the Caucasus to Switzerland to study philosophy, biology and geophysics, enlisted in search of adventure. As he himself wrote:"the rush to the riddle, the longing for the unknown burst the young breast". A year older Henryk Arctowski, geographer and geophysicist , and Emil Racovitz, 29, a Romanian zoologist and botanist, were the only ones to have a solid scientific background for the mission.

Probably none of the crew members even tried to imagine what awaited them in the Antarctic ice hell. And perhaps only Amundsen, who wanted to prove himself in extreme conditions like his idols - Fridtjof Nansen and Sir John Franklin - was ready to face whatever fate brought.

A completely different world

“We sailed into a completely different world,” wrote de Gerlache. - "Like the heroes of the Scandinavian sagas, cruel gods subjected us to inhuman tests." In his wildest fantasies, however, he could not have guessed how terrible these trials would be. The rest of the crew thought the ship had entered an ice pack looking for shelter before the storm. Only he and his deputy, Georges Lecointe, knew the decision was deliberate. The young commander of the expedition wanted to avoid the shame of failure at all costs. Reaching the latitude of 71 ° 31'S, he achieved a new record and improved by over twenty nautical miles the previous one:71 ° 10's, reached by Captain Cook. The price was that the ship was trapped in the ice - the ice pack closed . In his diary on March 5, De Gerlache wrote succinctly:“All sails are set. The ship will not budge. ”

None of the crew members even tried to imagine what awaited them in the Antarctic Ice Hell.

As an officer, Amundsen was told in secret from the others that the coordinates communicated to the crew were devised to maintain their morale. He noted in his diary that people were afraid of hibernating on ice . And that was what awaited them. In late February 1898, frost chilled the Bellinghausen Sea on the outskirts of Antarctica. After a few weeks, it was dark. March and April were spent in preparation for the polar winter - the ship was secured, snow banks were erected to protect against frost. As we read in the book Madness at the End of the World. Belgica's expedition into the darkness of the Antarctic night by Julian Sancton:

According to Lecointe's calculations, at this latitude the sun would disappear below the horizon for good by mid-May, and the polar night would last almost three months . No one doubted that the temperatures would drop significantly, but how much was unknown, because had never been so far south in winter in winter.

Trap of the Ice Sea

Uncertainty and fear quickly overwhelmed the crew. After all, such a scenario was not assumed at the beginning of the expedition. For the first time, people had to spend the winter in Antarctica. Initially they tried to fill their time with work . As Arctowski wrote in his journal:

We had to collect astronomical, magnetic and meteorological observations, observe the auroral phenomena, it took a lot of time to sound, measure the temperature of the sea depths, catch animals, hunt penguins and seals, excursions, and finally numerous daily jobs.

In time, the coal ran out. There was a shortage of adequate clothing and equipment, but most of all adequate food as people became ill with time was only found out. On March 21, 1898, Dr. Frederick Albert Cook wrote that they were trapped in the sea of ice. And de Gerlache bitterly added:"We are no longer seamen, but a small penal colony where convicts serve their sentences."

Not the first and not the last

When the sun disappeared below the horizon on May 19, and the long, Antarctic night took Belgica into its reign for a further 63 days, it turned out how hopeless the situation of the crew cut off from the world was. On July 6, Emile Danco, liked by his comrades, died. Undiagnosed heart disease prevented him from surviving the hardships of the polar winter. The Polish geologist Henryk Arctowski noted in his memoirs that in the twilight a body wrapped in a Belgian flag was carried to an ice hole in order to return it to the sea. And Dobrowolski added to his dad on June 8 and 9:“Goodbye, goodbye, Lieutenant Danco! You are not the first, and you are not probably the last. Maybe we will meet"! Maybe even this winter! ”.

The text was inspired by Julian Sancton's historical novel Madness at the End of the World. Belgica's expedition into the darkness of the Antarctic night, which has just been released by Media Rodzina.

In an atmosphere of all-encompassing darkness, doubt and hopelessness, fear poured into the hearts of the crew. Julian Sancton quotes Cook's account:

It is not difficult to read from the faces of my companions their thoughts and deeper grief. At the tables, in the laboratory and in the crew quarters everyone sits sad, resigned and apathetic, lost in melancholy deliberations from which, from time to time, one breaks out, driven by an impulse of empty enthusiasm. […] Every attempt to instill the light of hope fails.

A New Hope

Amundsen was perhaps the only crew member who did not despair. He liked the fact that nature is challenging man to face him - or he will die. On June 20, 1898, he wrote that for many years this was the life he wanted and that joining the journey was not a puppy, naive dream, but a mature decision. He wrote that he did not regret anything and hoped that his health and strength would allow him to continue his work. He even liked the food his friends came out sideways.

When on July 22nd the sun rose again to the sky as we read in the official report from the expedition - a new hope has returned. Commander de Gerlache noted in his journals:“Our eyes were struck by this colorful vision. Only those who have been deprived of the sun will be able to understand how much good it does for the body and soul. Only then can one understand the worship that the primitive peoples give to the sun and have placed them in the pantheon of their deities from time immemorial. "

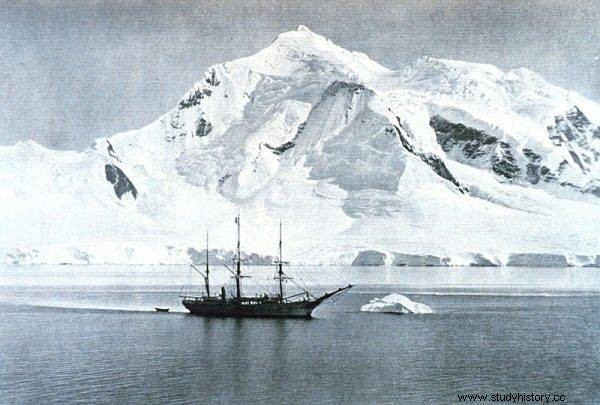

photo:Belgica public domain anchored at Mount William

Morale did improve, but the crew were in such terrible health that many of the men did not get up from their beds . De Gerlache and Lecointe wrote their wills, seeing no hope of leaving the Ice Hell. Two Norwegian seamen, Adam Tollefsen and Engelbret Knudsen, started showing signs of mental illness. "His soul is plagued by hallucinations of terrifying fears," Lecointe wrote of Tollefsen. - 'Strange and mysterious:the word chose (' thing 'in French) makes him feel mad. Since he does not speak this language, he thought that chose meant "to kill" and that his companions commanded themselves to murder him. " And de Gerlache added that Tollefsen hardly ever sleeps, sees only enemies around him and avoids the company of his colleagues.

The silent killer

Meanwhile, Dr. Cook, who many years later went down in history with a lie about the conquest of the North Pole and the summit of Mt. McKinley, seeing half of the crew fail to rise from their beds in a state of physical and mental degeneration, gathered all his medical and polar knowledge to save his companions by superhuman effort . As we read in Madness at the End of the World :

He re-examined the ever-growing list of symptoms that all travelers had complained of, such as drowsiness, apathy, weakness, anemia, unnaturally pale and waxy skin and "subcutaneous exudates "- fluid build-up around the eyes, ankles and other parts of the body resulting in swelling.

Cook quickly realized that it was the almost forgotten scurvy that was taking such a terrible toll among the Belgian crew. The only way to fight it was to use Inuit methods: including penguin and seal meat with minimal heat treatment in the diet. People barely had the strength to put anything in their mouths. All the more they disliked the prospect of switching the canned food to meat that didn't taste very tasty and smelled foul.

Steaming and insane parades

Cook wasn't going to stop there. Another of his invaluable ideas to improve the health of the Belgian crew was "scalding", that is, spending time by the fire, which was supposed to replace the sun. He stripped his friends naked and placed them in front of a burning wood or coal stove. Not only did the heart rate improve, but also the mood. He also invented a lot of activities and entertainment to keep people from falling into apathy. He encouraged those who were able to stay on their feet to be physically active. He took them on daily walks around the ships. They were ironically called the "lunatic parade."

Various activities and entertainment were intended to prevent people from falling into apathy.

He also tried to introduce some fun into the daily routine and boredom. He ordered a grand celebration of birthdays, anniversaries and national holidays of individual countries. There was a feast and the champagne was opened. Not only that - he entertained his companions with games and contests, such as a beauty contest of photos of models and celebrities torn out of magazines of that time, or presentations of satirical drawings and caricatures made by Racovitz.

No women? So let's go!

The long period of crew isolation also had the effect of increasing sexual frustration. It manifested itself in constant discussions about the fair sex, fantasies and dirty jokes , with time growing to the main topic of conversation. "Amundsen and I were coping with this icy period of sexual deprivation," Cook wrote proudly. He scared the rest of the sailors that the polar night could make them sterile if they waste their time on shameless chit-chat. The sooner they let go of all thoughts about women, the better their chances of staying healthy. Instead, he recommended an iron regime and a fixed schedule of the day, indicated by the hours on the clock. As reported by Sancton:

Work began at eight in the morning and lasted until five in the afternoon, with breaks for lunch and exercise. Dinner was served at half past six, and the rest of the evening was devoted to rest and relaxation under the dim light of the kerosene lamps. At that time, sailors played cards, mended clothes, or read. When a bright moon appeared in the sky, the weather encouraged daredevils to stroll on the ice pack.

Beauty at Earth's End

Ultimately, thanks to an ingenious, energetic and optimistic physician, the sick recovered and regained their spirit. At the head of commandant de Gerlach, who initially refused to eat penguins and seals.

"I eat a lot, at least twice as much as before," wrote Dobrowolski, who had been bedridden not so long ago. - “My appetite is unheard of… I don't feel weary anymore. I sleep perfectly and a lot. I shit regularly. The future head of the National Meteorological Institute in Warsaw, when asked years later what his stay in Antarctica had taught him, replied that to see… beauty. He found his passion and meaning in life in the branch of science he had created - cryology, dealing with all forms of ice, including nature's masterpieces - frost particles.

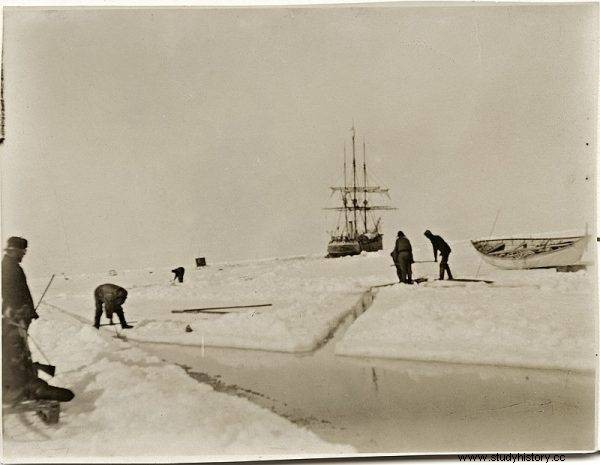

Everything had to be done to free the ship. Explosives were used for this purpose.

Lecointe's health had also improved by the end of July. Together with Cook and Amundsen (who did not question medical recommendations and ate raw meat from the very beginning), he went hunting so that his sick colleagues could be provided with supplies of penguin and seal meat.

In thirty days, ten years came

With the advent of warmer, sunnier days, the health of the members of the expedition improved significantly. Nevertheless, by the end of the year it became clear that the second such winter the Belgian team would not be able to survive . Everything had to be done to free the ship. Explosives were used for this purpose . People were trying to pierce the frozen surface with pickaxes, saws and axes. Once again, Cook proved to be an invaluable member of the crew. It was he who came up with the idea of how to most efficiently cut a channel in the ice through which the ship could go out into the open waters.

After a total of 13 months in the chains of ice, Belgica went to sea on March 14, 1899, and reached the port of Punta Arenas on March 28, 1899. People whose appearance was the best proof of the suffering and hardship they had endured had descended from the deck. “In just thirty days, we were each ten years,” noted Cook. “Our skin has grown rough like a nutmeg grater. We had long hair full of tangles and gray, even though the oldest of us was not yet thirty-five. "

In a madhouse

In the official report from the expedition, published in Brussels in 1904, we read a short but poignant description of the Belgian crew's struggle:

Day after day, the members of the expedition grew weary body and mentally. Everyone tried to do their job, but did it with great difficulty. Polar anemia has hit almost everyone. For many, the heart rate jumped to 150 beats per minute, for one it dropped to 47. The urge to eat something fresh was strong and painful. Officers and crew began eating penguin and seal flesh. In mid-winter, Commandant Gerlache and several other members of the expedition experienced symptoms of scurvy.

The report also reads about "attacks of hysteria" in one of the sailors, and about the mental illness of Tollefsen, who "witnessed the pressure of the ice, succumbed to the terror and lost his mind." Arctowski wrote it emphatically: "We're in a madhouse." It is therefore not surprising that when Admiral Rychard Byrd went on an expedition to Antarctica three decades later, took two coffins and 12 straitjackets with him .

Cook quickly guessed that the almost forgotten scurvy was taking such a terrible toll among the Belgian crew

In France and Belgium, the commander of the expedition and the crew were greeted as heroes. The imported materials and samples, as well as photos and observations, a large part of which were published in 10 volumes, formed the basis of modern geological, meteorological, glaciological and oceanographic studies of the polar regions. If we remember Amundsen's words that the human factor is three-quarters of every expedition, then it is easier to understand, therefore NASA wants to use the experience of polar expeditions, which are the closest substitute for long extraterrestrial journeys.

Winterworm syndrome

The issue where Belgian's expedition proved to have the greatest impact on NASA research was highlighting the devastating physiological and psychological impact of extreme expeditions on its participants . Which was described in great detail by Dr. Cook. He believed that a mixture of fear, insecurity, isolation and monotony not only made you insane, but it also turns people against each other. As Sancton writes, quoting the doctor's account:

If we could only find some freedom from each other, for just a few hours, perhaps we would learn to see it all from a different point of view, we would be interested in each other's company; but, alas, it is impossible! The truth is that we are all tired of each other, as well as tired of the monotony of the black night .

Over the past decades, research on the scientific and technical staff of year-round South Pole bases has regularly demonstrated similar physiological and psychological problems to those experienced by Belgian seafarers. Cook referred to these symptoms as the collective term "polar anemia." Today, scientists use the term "winterworm syndrome" . Despite many hypotheses, they still cannot explain the causes of the ailments. They also cannot estimate to what extent astronauts on long space missions would be exposed to this condition.

The anthropologist and behaviorist Jack Stuster, working as a consultant for NASA, used Belgian crew documents to plan a three-year mission to Mars. In his opinion, space missions will resemble much more sea expeditions than test flights . Stuster was also involved in designing US space stations for research into crew productivity in situations of prolonged isolation and isolation. He tried to answer the questions:how long do astronauts hundreds of thousands (and more) of kilometers from home survive, seeing the darkness outside and the same faces around them? How can I help them avoid depression and apathy?

Where is Antarctica and where is Mars?

Based on research conducted on Belgian missions and other research expeditions, Stuster concluded that what held the crew members together was the "spirit of the expedition". Admired by Amundsen, Fridjof Nansen, who set off for the Arctic in 1893, perfectly planned his expedition. He thoroughly completed the crew and took care of maintaining morale. On Christmas, a feast of reindeer meat and currant jam was held with celebration and singing. Nansen wrote then in his diary that their relatives at home were probably worried about them, but the sympathy would probably drop immediately if they saw the atmosphere of celebration and smiles on the faces of the participants of the expedition.

Cook referred to these symptoms as "polar anemia." Today, scientists use the term "winterworm syndrome".

This was one evidence for Stuster that caring for your surroundings helps to avoid psychological problems. He believed that windows in spacecraft are essential to avoid vision problems that have touched submarine crews on long missions. The interiors had to be designed accordingly. At least with attention to soothing colors (although Chris Hadfield in the Cosmic Guide to Life on Earth complained about the salmon walls in the ISS). He recommended an artificial division of the day into day and night to avoid the phenomenon of insomnia typical of remote Antarctic research centers, and to prepare meals in the most varied way possible so that mission participants would not have to eat the same pulp over and over.

And - as he considered it necessary - before the trip to Mars, the crew had to be tested under conditions of extreme isolation. It would test to what extent people experiencing severe stress and being in a situation similar to imprisonment are capable of maintaining interpersonal relationships. As astronaut Tim Peake wrote, in stressful conditions and situations, when teamwork and communication are required, people have the opportunity to "get to know themselves and others". The experience of many expeditions and expeditions shows that the sooner this happens, the better for themselves and the fate of their missions.

The text was inspired by Julian Sancton's historical novel, Madness at the End of the World. Belgica's expedition into the darkness of the Antarctic night, which has just been released by Media Rodzina.