Treasury fees have always aroused opposition from the public. But did the peasant or the burgher really have anything to complain about?

The tax was invented even before the money was in circulation. In addition to the fee in the form of livestock or agricultural produce, peasants in the early stages of Poland's existence could pay with, among others, animal skins. Only when silver pennies began to be minted, and material goods could be exchanged for coins, taxes began to take a slightly more complicated form ...

First taxes

The fees paid by the subjects to the ruler's treasury had the nature of a tribute in kind at the beginning of the Polish state's existence. Their height and character were determined by the princely law, which in its nature was derived from the earlier family and tribal customs.

These taxes took various forms and names, but always consisted in the transfer of a certain number of goods:pigs, cattle, sheep, grain. The subject paid counseling, which was later replaced by Ian, and from 1629 - chimney . The size of the counseling center depended on the size of the cultivated land, as did the size of the field tax. Smoke, in turn, was paid per inhabited house and depended on its size and the city in which it was located. Later, already in the 18th century, this tax was calculated on the basis of the number of chimneys on the roof.

Smoke, in turn, was paid per inhabited house and depended on its size and the city in which it was located

At the beginning, the payment of the obligatory sum was confirmed by the so-called narzac, i.e. a double incision of two parallel sticks by a tax collector. One of the sticks stayed with the payer, the other went on with the clerk. If in doubt as to whether the fee had been paid, it was possible to make sure by putting the poles together again.

It should be noted that the current ruler was also subject to fees. When calculating his income, he had to deduct the tithing that was paid to the church. In time, not earlier than from the second half of the 12th century, the fee was transferred to its knights and the subject population. In Poland, tithing persisted until the 19th century. It was abolished in Galicia in 1848, in the Kingdom of Poland in 1864, and in the Prussian partition in 1865.

For home, for king, for life

Of course, this is not all the taxes that the rulers treated their subjects. First of all, before the nobility and clergy came to the fore, the king could impose fees himself, and often there were situations where additional fees were collected from subjects for greater needs of the state - for example, to support a larger army. Separate forms of taxation also had to be introduced for the needs of the newly created class of population, ie the townspeople.

The townspeople were charged with the highway, i.e. the city property tax, which later evolved into a more universal form of early income tax. It was also collected from those city dwellers who did not have large, quantifiable wealth, but provided services or were craftsmen. Therefore, in larger cities, there has been a division into three separate taxes:real estate tax, tax on non-agricultural economic activity and poll tax, i.e. the so-called personal tax on belonging to one of the urban population groups .

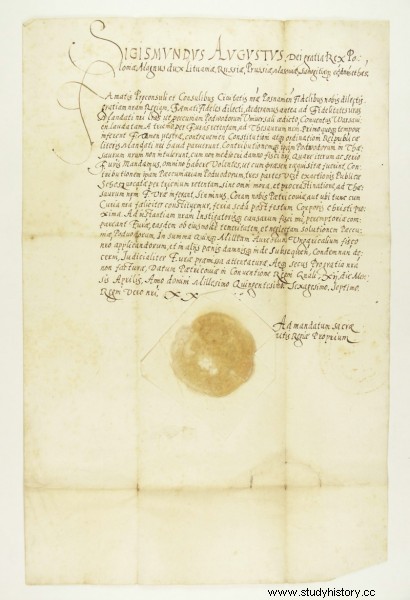

King Sigismund II Augustus, the king of Poland, calls on the city authorities of Poznań to pay the tax on livestock and road for the last three years, under penalty of 5,000 Hungarian florins

In the same period, an opolna fee could also apply, i.e. a lump sum in the form of one cow from Opole (administrative and tax unit), as well as a watchman, i.e. the obligation to provide guards to guard the rulers' sanctuaries.

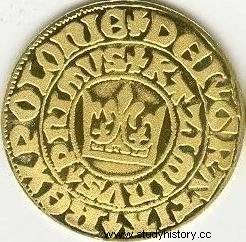

The form of paying taxes with the help of money appeared in the times of Casimir the Great; in 1338, silver pennies were minted. One penny was of high value at the time:historians estimate that one man could eat for it for almost a whole week.

Taxes not for everyone

As today, the tax burdens in medieval Poland did not apply to everyone. In the 14th century, the royal treasury was separated from the public treasury. The newly formed nobility, under the general privileges of 1374, were exempt from all taxes except 2 groszy of a field (2 groszy from a field in knightly estates). Similar privileges were obtained by the clergy in 1381, except that church agents paid 2 groszy of fief from episcopal goods and 4 from other spiritual goods.

The 14th century also brought a very significant change in the way taxes are established. Namely, the king could no longer levy new taxes for public needs on his own, but only with the consent of the noble and clergy state . Therefore, the collection of extraordinary taxes in exceptional circumstances (i.e. double or triple tax) had to be justified by a separate resolution of the Sejm.

Cracow grosz

And although these are not all the taxes that the subjects had to struggle with in medieval Poland, it can already be seen that the matter was not simple and obvious. Nevertheless, according to Professor Ożóg, a medievalist from the Jagiellonian University, the tax system was then more friendly to citizens than it is today . It was relatively less burdensome and, contrary to beliefs, it was not only used to supply the royal treasury or finance wars. Remember that tax revenues also served, for example, to maintain schooling or social welfare, as was the case with tithing.

It also turns out that the tax burden on the medieval population was relatively much smaller than today. As estimated by Andrzej Sadowski from the Adam Smith Center, the serf peasant worked for his master for two days a week. For comparison, in 2012 we worked to maintain the government until the middle of the year!

Where did the excise tax come from?

The excise tax began to take shape relatively late, because it was not until the end of the Middle Ages in the 15th century. It was related to a number of factors underlying the dynamic development of the state. There were more and more people, the nobility and bourgeoisie crystallized. Poland grew, but the threat posed by the Tatars and the Teutonic Order was also growing.

Strengthening the defense, i.e. then simply increasing the number of soldiers, was associated with high costs. The nobility was exempt from most taxes, so a new source of income was used:the townspeople. Due to the small number of developed cities (Kraków, Lviv, Lublin, Poznań, and after the end of the Thirteen Years War also Gdańsk, Elbląg and Toruń), there were relatively few "new" taxpayers. Nevertheless, the nobility feared a threat to their interests from this constantly growing social group, so they tried at all costs to limit their influence.

As estimated by Andrzej Sadowski from the Adam Smith Center, the serf peasant worked for his master for two days a week. For comparison, in 2012 we worked to maintain the government until the middle of the year

And so, in the second half of the fifteenth century, during the reign of Kazimierz Jagiellończyk, an excise tax called "czopowy" was adopted. The name comes from the plug closing a bottle of alcohol, suggesting that the initial tax was supposed to be on the sale of interest drinks . Scholars believe that the fee was initially around 1/8 for breweries and 1/18 for innkeepers (although these are indicative values as there was no standardized system of weights and measures yet). Taxes were also applied to goods imported from abroad.

It is estimated that in 1534 budget revenues from the "plug" constituted as much as 25% of tax revenues. This value was constantly growing and in the middle of the 18th century it was already about 33% of the total income of the state. The name "excise duty" appeared for the first time in 1658 at the Ordinance General Sejm, where the following was adopted:

“ Because we informed each other in the past, how needed the Republic of Poland is. the excise tax, he authoritate this Sejm after all Mystas and Towns, Crowns, Clergy and Nobility, we decide without excep- tioning anyone. ".

All the above-mentioned forms of taxation are of course a section through the entire epoch described in a very brief and generalized way. In some regions, some taxes have been levied longer than in others, and over the centuries, there are certainly dozens of temporary fees that have been made and passed away, all memory of which is lost.

Bibliography:

- Knap K., Worse than in the Middle Ages? Dziennik Polski, https://dziennikpolski24.pl/gorzej-niz-w-sred medievalu/ar/c3-3155520 [access:25.01.2022]

- Kociak N., History of excise duty in Poland. Still a tax on luxury goods? Kortowski Legal Review, 2017.

- Owsiak S., On the history of public tribute and tax . Scientific Papers of the Cracow University of Economics, Kraków, 2000.