After July 30, 1941, thousands of Poles deported deep into the USSR found themselves in a new situation. As part of the Sikorski-Majski pact, our countrymen got a chance to escape from the Soviet empire. More than 100,000 refugees moved south with Anders' army, towards Iran. But many have found a temporary home in a completely different part of the world - Africa. India, where over 5,000 Polish children found shelter, did not refuse to help the refugees.

Polish wandering has a long tradition that goes back several centuries. It began with the fall of the first Polish Republic. It was then that the first Polish exiles - the Bar Confederates, and then subsequent participants in the uprisings - went to the east - into the depths of Tsarist Russia.

The first refugee from these areas, which became famous all over the world, was supposed to be a Polish nobleman, Maurycy Beniowski. After him, many returned from Siberia, to mention Józef Piłsudski himself. In the Napoleonic era, legionnaires wandered around the world, who pacified and eventually settled in Haiti.

After several centuries of historical perturbations that resulted in migrations, escapes, displacements, deportations, it is really difficult to identify places where our countrymen did not go - be it as exiles, emigrants or refugees. Sometimes they found refuge in truly exotic places.

Japanese prologue

Let the story of orphans after the Siberian exiles be a confirmation of these words. Over 700 kids were saved from the hell of the Soviet Civil War in 1920 by the Far East Children Rescue Committee established by a Polish woman - Anna Bielkiewicz, daughter of one of the designers of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Together with Józef Jakóbiewicz, the son of a January exile, began searching for children in Siberian shelters, railway stations and abandoned settlements. The determined woman and her assistants appealed for help wherever they could.

The first refugee from these areas, which became famous all over the world, was supposed to be a Polish nobleman, Maurycy Beniowski. After him, many still fled Siberia

In 1920, Bielkiewicz traveled to Tokyo. There she met representatives of the Japanese Ministry of Defense. The help was possible and real, because Japanese troops were still stationed in Siberia. The Land of the Rising Sun did not refuse, although the Japanese knew almost nothing about Poland, especially since it was the time when the Republic of Poland had just regained its independence. In the years 1920–22, 760 Polish children were transported to Japan from Siberia. The rescued orphans were provided with decent living conditions. After some time they found their way to Poland.

Their history can be treated as a kind of prologue to the great escape from the east of thousands of our compatriots deported under the Soviet harassment in the interwar period and during the Second World War.

Sikorski-Mayski Pact

Exodus from "inhuman land" made possible the so-called amnesty, which is part of the agreement between the Polish government in London and the USSR. The British-forced Sikorski-Majski pact was to normalize Polish-Russian relations , thus constituting an important element in building the anti-Hitler coalition.

On August 12, 1941, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR issued a decree on amnesty for Polish prisoners of war, labor camp prisoners and all other repressed and displaced people from the borderlands of the Republic of Poland, which the Red Army entered on September 17, 1939.

In the search for Polish orphans scattered around the shelters of the USSR, the famous pre-war actress and singer Hanna Ordonówna and her husband Michał Tyszkiewicz.

Originally the list of people covered by the amnesty numbered over 380,000. names , however, as the situation on the Eastern Front changed in favor of the Soviets, their propensity to free Polish citizens (not only of Polish nationality) decreased. Most Poles in the USSR headed for the places where the Anders Army was formed.

In the search for Polish orphans scattered around the shelters of the USSR, the famous pre-war actress and singer Hanna Ordonówna and her husband Michał Tyszkiewicz. Largely thanks to her activity in Ashgabat, a Polish orphanage was established near the border with Iran, where children from all over the Soviet Union were sent. Ultimately, over 110,000 people were evacuated from the USSR - apart from the army, also 77,000 Polish civilians, including 20,000 children.

Wandering to Iran

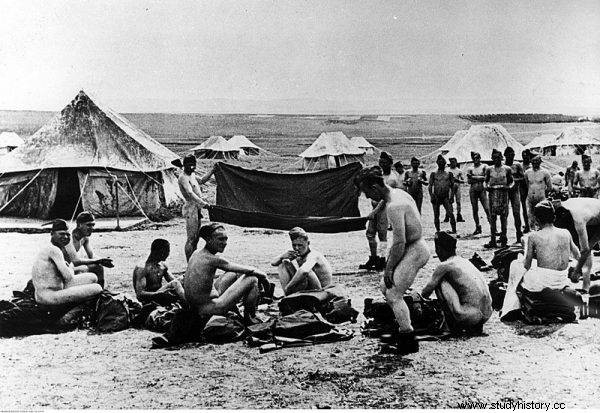

The river of Polish refugees, along with the Anders Army, flowed to Iran, then under British rule. Poles arrived there from March to September 1942 - mainly via Turkmenistan to the transit camp in Pahlevi, Iran (currently Bandar-e Anzali).

The exhausting journey and extreme weakness of people, often living in extremely difficult conditions in Soviet labor camps, resulted in the death of over 2,000 evacuees. They died from malnutrition, dysentery, typhus, and malaria. Helena Nikiel came to Pahlevi in August 1942:

We arrived at a port where we left the ship emaciated, dirty, lousy, with bundles on our backs or in our hands. My mother carried a sewing machine on her back and bundles of clothes in her hands. (...) My brother and I were carrying bundles of biscuits in our hands, and I was carrying a pot of fat on my back, which melted and ran over me and the dress I had grown out of a long time ago. (…)

And with such a long, stretched hose of paupers, we trudged along the deep sand of the beach, in the heat and with great hardship, to the tents that were waiting for us some 2-3 km away. We were so tired that we didn't even have the strength to enjoy ourselves, that the worst was over. It turned out that we said goodbye to the Soviet Union and we are on the southern - already Persian shore of the Caspian Sea, in the port of Pahlewi.

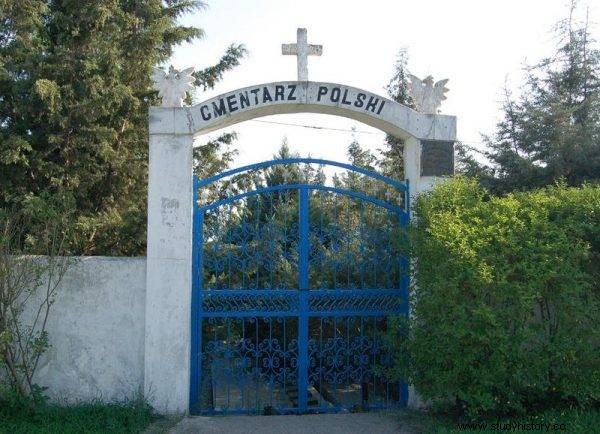

Poles arrived there from March to September 1942 - mainly via Turkmenistan to the transit camp in Pahlevi, Iran (currently Bandar-e Anzali, in the photo:Polish cemetery in this town).

The refugees were transported from the transit camp to Tehran. Eugeniusz Szwajkowski recalled:

After the second quarantine in mid-September, they drove us to the capital, Tehran. During the trip, during the stops, local ladies walked by our bus, offered us apples, cakes, etc. In Tehran, they put us in nice buildings, where it was good.

The refugees were accommodated in several places - the largest groups of Polish refugees were in Tehran and Isfahan. Helena Nikiel, who lived in one of the Tehran camps, described:

I found this camp as beautiful as a garden of paradise. It was located on the opposite side of Tehran (looking from Camp II), but also close to it. (...) The terrain was hilly. Cypresses, figs and pomegranates grew on all the hills. There was a lot of greenery, "arykas" or small, narrow streams were flowing. On the horizon, not too far away, could be seen the snow-capped peaks of the high Elburs Mountains.

(...) we lived in shacks which had very wide, open door openings at the front. There were also bunks (…). We received food from the shared boiler. They were taken into military flasks or canteens and ate somewhere under a bush.

The city of Polish children

Along with thousands of Poles, Polish administration taking care of refugees, military hospitals, orphanages and schools were established in the country of Persia - most often under the supervision of nuns. In Esfahan - known as the city of Polish children - 2,590 orphans were placed. On the spot, clergy (also Christian Armenians) organized Polish schools, kindergartens, gymnasiums, and a sanatorium. Living conditions were difficult. Sister Monika Alexandrowicz, who worked in the Polish camp in Esfahan in the years 1942–1943, reported:

The most terrible plagues were scabies and lice. Fighting them came with the greatest difficulty. (...) The monastery superior brought us medicines. (…) Every day the children were washed and changed into clean clothes. Dirty, she went to bags and was sent to the Sisters of Charity, who washed and cooked her. (…) No washing or cooking helped, they had to be destroyed mechanically, just like adult parasites. It was a hopeless fight.

Nevertheless, Polish institutions functioned, and with time the standard of living definitely improved.

Since the Delegation's inception in Persia, all children have been supported by its funding. It was then that the Polish colony in Isfahan developed dynamically. The plants prospered, learning and activities were perfectly organized thanks to the fact that the number of staff increased as needed . The children were healthy, they lacked nothing, they even got used to the climate. All this ensured their proper development. A new hospital was even organized for our use.

In Esfahan - known as the city of Polish children - 2,590 orphans were placed.

The memories of the Poles who found refuge in Persia remained a good opinion of the hosts, their kindness and willingness to help. Father Michał Wilniewczyc, working in the Isfahan camp, described:

Our relations with the Armenians and Persians were good. Especially in the beginning, the Persians were very service-minded towards Poles, especially Polish women. When Fr. Kantak and other Poles shook hands to greet the Persians, they were surprised and said:an Englishman will never shake hands with us. They were treated as lower class people. This was true not only in Persia, but also in the colonies in general.

However, the coexistence with the hosts was not always positive. For Poles, meeting with a completely different culture could be shocking. Sister Monika Alexandrowicz said:

The very fact that [the Persians] allowed the establishment and maintenance of a Polish post in Esfahan proves their generally friendly attitude towards us. They also helped us a lot, for example in the field of medical treatment:we used the advice of Persian doctors and their hospitals (...). All this proved that the Persians did not have a hostile attitude towards us as a foreign nation.

However, it turned out many times that some kind of innate wildness, and perhaps most of all habit of treating women (especially foreigners) and children as a kind of soulless workforce, as slaves - led to various excesses which often ended tragically.

“We were sometimes dreaded when there were religious marches of Persians, young men whipping themselves with wire brooms to the beat and singing. Then we got off the road and hid in our apartments; Mohammedans fanaticism is terrible, especially during their Ramadan fast ”- admitted priest Wilniewczyc. Tehran, on the other hand, is remembered as a city of contrasts. Helena Nikiel recalled:

The shop windows were beautiful, rich, but next to them whole families were lying on the pavement, but mostly mothers with children who were born here and died here. This surprised and terrified us. While we were also poor, the contrast between wealth and extreme poverty was too blatant. For us, the indifference of the rich to the fate of the sick and starving under their magnificent exhibitions, dripping gold and precious stones, was incomprehensible to us.

P Polish Africa

Poles did not stay long in Iran. Due to the uncertainty of the situation, the British agreed to further evacuation. Anders' army moved to Palestine. Civilians from the Persian camps were located all over the world - including India and British colonies in Africa.

As early as 1942, the evacuation of Poles to Africa began. In July 1942, the London government concluded an agreement with the governors of the then Tanganyika, Kenya and Uganda. Poles were also to go to northern and southern Rhodesia and the South African Union. Polish citizens were transported to British India (Karachi port in today's Pakistan), and from there to settlements on the African continent.

By the end of 1944, nearly 14,000 people had been transported to Tanganyika, Kenya and Uganda. Six settlements in which Polish refugees lived were established on the "Black Land":four in Tanganyika (Tengeru, Kondoa, Ifunda, Kidugala) and two in Uganda (Masindi and Koja). In addition to permanent estates, several transit camps were also created, incl. in Morogoro, Kigoma, Dar es Salaam, Iringa and Tosamaganga in Tanganyika.

Polish refugees from the USSR were at that time the largest European minority in East Africa. The largest Polish agglomerations on the African continent numbered several thousand people. They were created with the involvement of the locals. The costs of maintaining the refugees were borne partly by the London government, partly by the British (they added the expenses to the Polish debt).

Poles did not stay long in Iran. Due to the uncertainty of the situation, the British agreed to further evacuation. Anders' army moved to Palestine

The settlement in Tengeru in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) had about 5,000 inhabitants. It was one of the biggest. It had its own schools, including secondary schools, and an orphanage, there were scout instructors, a football team, a theater and a choir. Poles tried in all possible ways to make their lives similar to the realities of life in their homeland. Cucumbers, tomatoes and sunflower were planted under the African sun. State and religious holidays were solemnly celebrated.

The living conditions were very different - from difficult, like in Kondoa, where Poles lived in 403 clay barracks, to good ones. This was the case at the Ifunga camp, where 780 people were housed in 100 brick houses. The estate had its own kitchens, dining rooms, laundries and warehouses.

It is estimated that about 8,000 children passed through camps for Polish refugees in Africa. Most of them were unaware of the difficulties and anxiety in which the elders lived. It was a blissful, enchanted world of childhood, after which exotic memories remained (the documentary "Africa of my childhood" directed by Ewa Misiewicz can be a testimony.

Polish Children Camp and good maharaja

Some of the refugees from the USSR after Iran ended up in India. In 1943, over 5,500 Polish children found shelter in the transit camps in Balachadi and Valivade.

The first camp for small refugees was established on the initiative of the maharaja of the northwestern Indian principality of Nawanagar - Jama Saheba Digvijaysinhj. This aristocrat and diplomat with sympathy for Poland (he met Ignacy Paderewski in the 1920s in Switzerland) strongly advocated building a housing estate for Polish children. He pointed to its location near his summer residence.

The first camp for small refugees was established on the initiative of the maharaja of the northwestern Indian principality of Nawanagar - Jama Saheb Digvijaysinhj (in the photo with a group of Polish refugees).

This is how the Polish Children Camp in Balachadi was established. Maharaja, who was personally involved in its construction and arranged for the financing of the investment from the funds of the House of Indian Princes, often visited the camp himself, apparently enjoying the great sympathy of the youngest.

Supposedly, when asked by General Sikorski, what he wants from Poland as a thank you for the good shown, he replied:"In liberated Poland, name one of Warsaw's streets with my name" . His expectation was fulfilled. Today in Warsaw's Ochota district there is a square of Good Maharaja with a monument commemorating Jama Saheba Digvijaysinhj.

Communists call for PRL

After the war, the communists who took power in Poland pressed for repatriation as soon as possible. The Poles, however, were not eager to return to the country arranged in the Soviet fashion. They did not trust the state administrators under Moscow's tutelage.

In India "Good Maharaja" in cooperation with the commander of the Polish camp, Fr. Franciszek Pluta and the commander of the estate, Lt. Col. Geoffrey Clark, made a court-verified group adoption of children. The settlement in Balachadi still existed a year after the war, later it was connected with the larger Polish camp in Valivade near Bombay. The further fate of several thousand Poles in India was different. Some of them stayed on the spot, creating a small Polish diaspora in this great country. The rest have gone over the world.

A similar fate awaited Polish settlements in East Africa. Only 3,800 people decided to return to communist People's Poland, which was only 20 percent of the total number of Polish refugees. Others remained in Africa in post-war camps financed by the United Nations. In 1949, an action was carried out to reunite military families from the Polish army in the west, who ended up in Great Britain. In this way, about 9,500 people left Africa for England.

Other countrymen traveled around the world - to the United States, Australia, Canada and France. Nevertheless, the refugee settlements in Koja and Tengeru continued to function until 1952. Later, only a few hundred people remained in Tanzania. Edward Wójtowicz, the last Polish refugee from the USSR to Africa and tied himself with Tanzania, died and was buried in Tengeru in 2015.

To this day, the fate of Polish wanderers from World War II in Tengeru - a small African settlement, several kilometers from Arusha, is evidenced by a memorial plaque in a small museum and a cemetery with the graves of Polish refugees who found shelter in this part of the world.

Internet:

- Persia in the memories of Polish refugees , Szlaki Tułaczy.pl, access:10/09/21.

- Polish exiles from World War II - Poland in Tanzania , Gov.pl, accessed on:10/09/21.

- Polish orphans in India - Soviet repressions , Information Center on the Victims of World War II, accessed on:10/09/21.