The famous terracotta warriors are just a part of the gigantic mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of unified China, who reigned between 221 and 210 BC.

In fact, the complex, located 30 kilometers east of Xian in the northwest of the country, houses more than 400 tombs covering an impressive 60 square kilometers. More than half a million workers worked on it for 38 years, following a meticulous plan that sought to reproduce the entire known China on a scale.

The main chamber, where the emperor's tomb is, has never been opened . The Chinese government, according to the recommendations of the archaeologists who work on the site, does not allow it to be opened and examined until it is in possession of the technology that allows it to safely prevent whatever is inside from being damaged. It may take years, decades or centuries for that to happen.

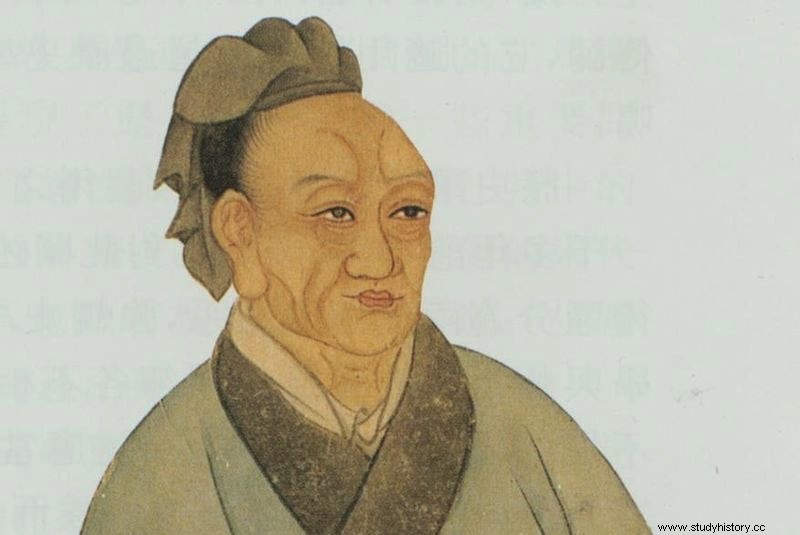

But then, how do we know what is inside the tomb? The answer is called Sima Qian. The considered father of Chinese historiography lived between 145 and 86 BC. and wrote a comprehensive history of the kingdom that spans more than 2,000 years retrospectively from his own time.

Known as Shiji (Historical Records ), had been started by his father Sima Tan, and was completed by Qian in 91 BC, about five years before his death. It tells the story of the construction of the great mausoleum, the burial of the terracotta warriors and concise data is given, such as the number of 700,000 workers involved in the colossal work.

When his writings were examined by Western historians they were taken with much skepticism, as exaggerations and even mythical legends with no historical basis. This was partly justified because Qian tends to present legendary and even mythological figures from Chinese history as historical facts, assigning them precise chronologies.

However, the archaeological discoveries of the last decades have confirmed many of the statements of the Shiji , such as the Terracotta Warriors and the location of the tombs of other rulers. So Qian's claims today are taken with great caution, hence the reluctance to open Qin Shi Huang's tomb.

Because nobody knows exactly what is inside, but Sima Qian affirms that in the great underground palace, larger than a football field, there is a scale reproduction of China known at that time. Including more than a hundred rivers, lakes and seas. A kind of microcosm where large amounts of mercury would have been used instead of water. to simulate the flow of rivers.

Is it possible that Sima Qian is right about this too? In the 1980s, researchers from the China Institute of Geophysical and Geochemical Exploration found that the soil around the tomb contained considerably higher concentrations of mercury than the rest of the region. While in remote locations in the area the soils contained an average of 30ppb (parts per billion) of mercury, the average above the chamber was 250ppb, and in some places it reached 1500ppb. Some of the archaeologists working on the site believe that it is a very feasible possibility.

Especially when the latest tests carried out to measure the resistivity of the soil revealed an intriguing terrain feature. A phase anomaly that occurs when an electrical current is reflected by a conductive surface, such as metal.

Additionally, analysis of the distribution of mercury levels revealed that it was highest in the northeast, then the south, while the northwest corner had very low levels. Superimposing this distribution on a map of China curiously coincides with the location of the two great rivers of China, the Yellow and the Yangtze, seen from the ancient Qin capital, about 30 kilometers from the monument.

According to Yinglan Zhang, who led the excavations between 1998 and 2007, there should be many other cultural artifacts and relics buried in the main chamber and other tombs around it, possibly things beyond our imagination . But he, too, thinks the distribution of mercury may not be a reliable indicator. The chamber may have collapsed thousands of years ago, just as the pits containing the Terracotta Army did. The mercury may have volatilized and drained through the ground over centuries.

Keep in mind that the terracotta warriors were found outside the wall of about 2 kilometers that surrounds the main chamber. Inside the wall were found buildings that contained food and other objects that the emperor might need in the afterlife . It is equally possible that the emperor was not buried alone. Sima Qian claims that many officers were buried with him, although it is unclear whether they were alive or dead at the time. Many of these buildings and objects could be gilded using gold and silver diluted in mercury as pigment, a common practice at the time.

If it were the case that the detected mercury had been used for these decorative purposes, specialists doubt that there would be a large quantity. Based on estimates of mercury production in the Song era, they believe that at most we would be talking about 100 tons, about 7 cubic meters. We may never know what secrets Emperor Qin Shi Huang's tomb holds.