When British prisoner Captain Robert Campbell received, through the Red Cross, a letter informing him that his elderly mother was dying and had expressed a wish to see him one last time, he could not have imagined the turn things would take.

Campbell had joined the British Army in 1903. At the outbreak of the First World War he was in France, as a company commander of the 1st Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment. In the fierce fighting that followed, Campbell assumed command of the battalion, as the oldest living officer. However, in the next German attack, Campbell was seriously wounded and captured.

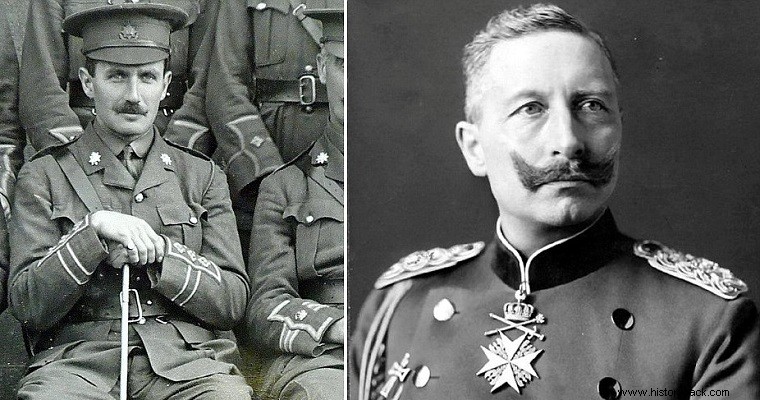

The Germans took him to a hospital in Cologne, where he recovered, and then to a POW camp in Magdeburg. There, in 1916, his mother's letter found him. Campbell was desperate and in this situation he decided to write a letter to the German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm, asking for the impossible, namely to be allowed to visit his dying mother.

Much to everyone's surprise the Kaiser actually gave the British captain two weeks' leave, on the condition that he give his word as an officer that he would return. Campbell accepted and gave his word of honor "as a man and an officer," as he said, that he would return.

What is also surprising is that the British administration also agreed, and after theGermans handed Campbell over to the British lines, he was allowed to travel on a special waybill, by rail and ferry, to his home in Gravesend, Kent, where he arrived on November 7, 1916.

He remained there a week and then made his way back to the POW camp in Germany. The British administration, respecting the captain's word of honor, facilitated his return and did not forbid his return, as might have been reasonable, but not honest.

So Campbell returned to the POW camp. His mother finally died in February 1917. Campbell later tried to escape but was captured. He was finally released when the war ended. He remained in the British Army until 1925 when he was discharged. He returned to the army in 1939, with the start of World War II, serving, due to his age, in auxiliary positions. He died in 1966 at the age of 81.