The Thirty Years War was one of the deadliest conflicts in history, with human losses comparable to the First World War, in the order of 8 million souls. The war is characterized by some as a "religious" conflict between Roman Catholics and Protestants, but that was not all. Like all wars, this one – in Clausewitz's interpretation – was nothing more than a clash of rival politicians by other means... aimed at weakening the power of the Habsburgs.

The war was fought in several phases, but the initial successes of the Habsburgs were reversed by the intervention of the Swedish king Gustaf Adolf and of his magnificent army. Despite the death of their king, the Swedes, with French (Roman Catholic… anti-Roman Catholic) gold, continued the war, terrorizing their opponents. However, the almost invincible army of the Swedish kingdom until 1634 (many of its men were German mercenaries, but also Scots) when it suffered its heaviest defeat that would have put it out of the war for good had it not been for French money.

Maneuvers and forces

After the victory at Lichen (1632) which cost them their king, the Swedes were disorganized. But finally in 1634 together with German Protestant forces (Army of Swabia and Army of Franconia) under the Swedish (of Finnish origin) general Gustav Horn and Prince Bernard of Saxe Weimar , respectively, moved into southern Germany with the aim of invading Bavaria, a staunch ally of the Habsburgs, with the aim of putting it out of the war once and for all with fire and iron.

The threat was too serious to ignore, so the Habsburgs formed a mixed Austro-German army (18,000 men) under Crown Prince Ferdinand (and emperor since 1637) which moved from Bohemia with the aim of cutting off the supply route of the Swedes and their allies. When Horn was informed of the enemy's movements, he turned north with the aim of attacking and destroying the Austro-German army against which he was numerically superior.

Horn took this decision also because he knew that another enemy army (15,000 men) under Prince Ferdinand's nephew, also Ferdinand, Cardinal Primate of Spain and son of the Spanish king was coming to Bavaria from Italy. So he wanted to successively defeat the opposing armies. But Horne didn't move fast enough. The Austro-Germans advanced as far as the city of Nürdlingen which their opponents controlled and besieged. Cardinal Ferdinand's army soon arrived there.

Thus the Austro-German army joined the Spanish, now fielding 20,000 infantry, 13,000 cavalry and 50 guns. On September 5, 1634, Horn arrived against this force with Saxe Weimar at the head of 16,300 infantry, 9,300 cavalry and 68 cannons. The "Swedes" were outnumbered by their opponents, but superior in artillery and partly in quality, so Horn decided to attack.

The blood is flowing

Horn and Saxe Weimar were both highly experienced generals. Thus they were not afraid of the numerical superiority of their opponents which was not overwhelming (25,600 against 33,000) and decided to stay and fight. But they made the mistake, also due to the difficult terrain, of not allowing their infantry to move with the 3-pounder direct support guns that they had and which constituted, in all battles, a power multiplier for the "Swedish" infantry.

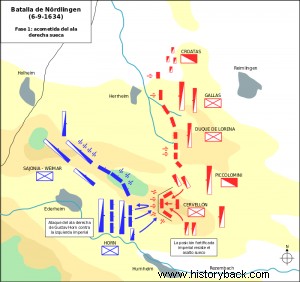

The two Ferdinands ordered their army west of the city. They supported their left flank on a hill north of the village of Hamheim and the small Retzbach river. There they sent a significant part of their artillery and infantry supported, on either side by cavalry and having on their right the German cavalry of General Piccolomini. The rest of the infantry lined up in the center supported by cavalry and artillery. At the far right were the famous "Croatian" light horsemen (Balkan horsemen, "ancestors" of the hussars).

The Protestant generals each took charge of one horn of their army. Horn took the right, arranging his forces in four lines of infantry, cavalry, infantry and cavalry again with the aim of capturing the hill on which the enemy's left flank rested, while Saxe Weimar took over the left horn with the rest of the forces. Horn's plan was simple. He intended to crush the enemy forces on the hill and then "envelop" the enemy army moving from South to North, while Saxe Weimar would engage him head on.

Massacre on the Hill

At dawn on September 6, Horn began his attack. But things did not go well from the beginning. At first his cavalry, pressed by enemy artillery fire, moved singly leaving the infantry exposed. But his infantry didn't fare any better either, marching through the forest, one of his brigades mistook the other for enemy and started firing at them!

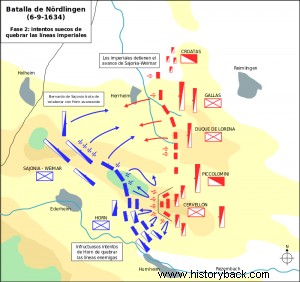

Nevertheless, Horne managed to get in order and attack, almost taking the hill in the first charge. But Cardinal Ferdinand did not panic, but immediately sent his famous Spanish Terthio against Horne's men. A fierce hand-to-hand fight ensued. Horn's men launched 15 consecutive attacks against the hill but the Terthios remained steadfastly supported smartly by Piccolomini's horsemen.

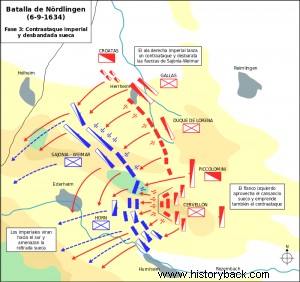

In the meantime, Prince Ferdinand, seeing Saxe Weimar not attacking and sending reinforcements to Horn, weakening his forces, he attacked. The Austro-German forces rushed forward and in no time completely routed Saxe Weimar's forces, who fled revealing the flank of Horn's forces still fighting for the hill. Soon Horn's beleaguered men were being slaughtered by the hundreds, while others simply surrendered.

Horn himself was captured. The battle was an utter disaster for the Protestants. About 17,000 of their 25,600 men who took part in the battle were killed and 4,000 captured. Indicative of the stubbornness and relentless struggle or the huge numerical difference in dead and wounded of the defeated. The victors had about 1,500 dead and 2,000 wounded. It was a triumph that did not bring, thanks to France, the end of the war.