In 1700 a new war broke out in long-suffering Europe, that of the Spanish Succession. France and the Habsburg Empire (Empire from here) were again rivals on three fronts (the Low Countries, the Rhine, northern Italy). On the Italian front, the Italian state of Piedmont had sided with the French. On the Italian front the Empire had entrusted the command to its best general, Prince Eugene of Savoy.

The Franco-Italian forces, under the French marshal Vendôme, had taken the initiative of the movements. Vendome attacking from the beginning of 1702 occupied Modena and reached Luzara, a small town on the river Po. The Franco-Italian army of Vendome numbered 30,000 men (49 infantry battalions, 103 cavalry regiments). Against her, Eugene had 25,000 men (38 battalions, 80 islands).

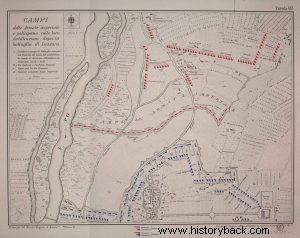

Eugenius was loosely besieging Mantua but when he heard of the arrival of the enemy at Luzara, which was guarded by only 500 of his men, he hastened thither at once, sending a message to the garrison, conjuring them to hold until he himself arrived with his army. Unfortunately the small garrison could not hold out and the city had been captured by the enemy when Eugene arrived in the area on 14 August. Between the city and the Po, two dykes had been built to prevent any drainage of the river. One of the mounds was built near the city and the second near the river.

After carrying out a reconnaissance of the terrain, Eugene decided to take advantage of the embankments, covering his forces behind them in order to attack the enemy by surprise. Eugene ordered his forces into two lines, personally taking command of the center, entrusting the command of the right to the Lorraine marshal Vaudemon and the left to the Prince de Commerce, also of Lorraine.

The next day, August 15, the imperial forces crossed the Po but were noticed by the French. Immediately Eugene ordered their deployment in battle formation and the immediate attack on the enemy. But it was already afternoon. Nevertheless the imperial right horn under Vaudemont attacked with vigor inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy. However he found against him the brave Irish mercenaries of the French who fought heroically. Four times the Imperials attacked and four times they were repulsed. Losses were heavy on both sides. The Irish suffered terrible bleeding but did not "break".

At the same time the Imperial left horn of Commerce also spearheaded the Imperial Danish mercenaries. The hard-nosed and "cold-blooded" Danes almost broke through the enemy lines, but in the end the Franco-Italians held out, despite the losses. The same more or less happened with the attack of the forces of the imperial center. When night fell the battle continued in confusion, with ferocity but without cohesion. Finally around midnight the two opposing armies separated. Eugene had losses (dead, wounded, missing) of 2,000 men.

His opponents suffered twice as many casualties as he did. It was a useful tactical victory for Eugene by which he halted the enemy attack and severely decimated the enemy. The two armies remained face to face in the area for some time. One of the indirect consequences of the battle was the subsequent change of camp of the Italians of Piedmont, who allied themselves with the Empire. At the beginning of 1703 Eugene was recalled from the Italian front. Other fields of glory were opening for him in Germany, in spite of the side of the invincible general the Duke of Marlborough.