In 1860 the Austrian Army was not at the height of its power. The defeat of 1859 by the French and Italians of Piedmont had cost materially and morally. Despite this, the Habsburg emperor Francis Joseph did not dare to proceed with the necessary reforms.

The consequence of the defeat of 1859 was the placement in the chief strategy of a new, popular, but completely incapable of managing large formations general, Ludwig Benedek. Under Benedek there was no improvement in the fighting ability of the Austrian Army, which, in any case, was possessed by an unbridled conservatism.

Benedek, in order to secure his position as head of the Austrian Army, made sure to place in key positions his friends and associates, usually as incompetent as himself. In 1864 Austria and Prussia declared war on Denmark over the possession of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.

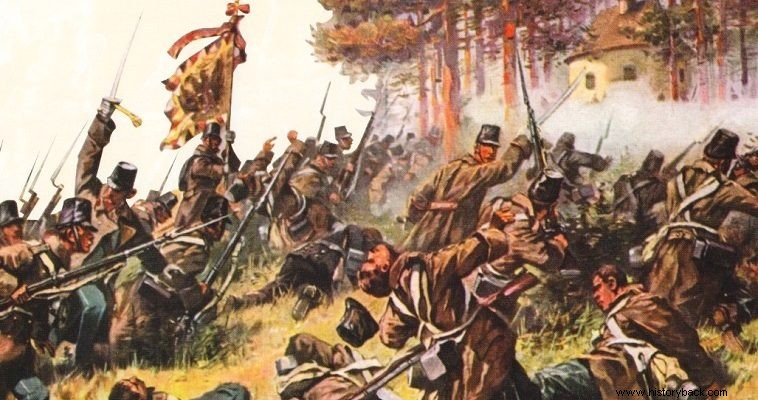

In this conflict against a small force and a weak army the weaknesses of the Austrian Army and its leader did not show . What was shown was the might of the Prussian Army, equipped with the breech-loading Dreyse needle rifle. . This fact was not evaluated properly by the Austrian leadership. The result was, in 1866, that the soldiers were reaped, like ears of corn, by the modern Prussian rifles.

After the 1859 defeat by the French and Italians, the Austrian Army decided to adopt the French tactical doctrine, which was an offshoot of the Napoleonic counterparts, adapted, slightly, to the new weapons of the time. This doctrine provided for the deployment of the infantry in attack phalanxes, which had to attack the enemy with the bayonet, at the greatest possible speed, covered by sniper units, with the enemy artillery weakening, with its fire the enemy infantry and, if possible, to disable, at least, the opposing artillery.

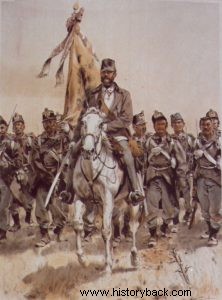

Cavalry undertook missions of reconnaissance and flanking, mainly, but when required also advance against enemy cavalry or artillery, preferably. Infantry equipped with muzzle-loading rifles could deliver a greater volume of fire at greater range and with greater accuracy than Napoleonic infantry.

Austrian infantry were equipped with the front-loading rifled Lorenz rifle . This weapon had begun to equip the Austrian infantry since 1854. It had a caliber of 13.7mm . The rifle was produced in three versions, the infantry one, a shorter barrel for acrobats and the Arabida version for cavalry.

The infantry version was 1.35 m long and weighed 4.1 kg. Infantrymen also carried a long bayonet. A well-trained soldier could fire three rounds per minute, but in general his rate of fire, in combat conditions, was significantly less after the barrel was gradually muzzled by gunpowder residue.

The Austrian infantry deployed for battle in battle phalanx formation, on a battle front. Thus a battalion presented a front of two and a depth of three companies. These formations were massive and presented large targets. However, they could be easily controlled precisely because they were compact and could move at a speed of up to 120 steps per minute .

Usually, however, battalions were deployed to attack half-battalion phalanxes. In front of the phalanxes, the elite Hunters , that is, the skilled snipers of the Austrian Army, who covered the common infantry with their fire. Unfortunately, in several cases these elite units were used as common infantry. The Austrian artillery had modern, for the time, breech-loading rifled guns of 4-12 pdr.

Cavalry was divided into medium and light. The first category included the cuirassier regiments, which no longer wore breastplates , and those of dragons . In the second category belonged the regiments of hussars and spear-bearing ulans . Hulans carried lances about 3 m long. Cuirassiers and dragoons carried long straight swords, while hussars and lancers carried curved swords. Dragoons and hussars also carried arabesques, while cuirassiers and lancers carried pistols.

The army was deployed with the artillery in front or on territorial outcrops, so as to have a wide field of fire and the infantry behind, in particularly dense formations. A regiment of three battalions deployed its battalions at a distance of only 4 m from each other. The snipers were deployed in front of the infantry, in a sniper formation, acting in pairs. The cavalry covered the flanks, but also depending on the tactical situation, carried out reconnaissance in depth, or was kept as a reserve in order to jump into battle when the friendly infantry would have succeeded in opening breaches in the enemy formation.

Two infantry regiments made up a brigade. Two brigades, along with an artillery squadron and sometimes cavalry elements, made up a division. Two divisions constituted an army corps and two or more corps an army. The cavalry was also organized into brigades of the two regiments and divisions of the two brigades, reinforced by mounted artillery. Artillery was organized into regiments, but operated mainly at squadron level. Acrobolists were organized in independent battalions.

The great weakness of the Austrian Army was its inhomogeneity, as its units were composed of men from all the nations of the Habsburg Empire , who in several cases, were in no mood to die for their overlords. In order to transform this heterogeneous group into a real army, a high unit spirit was needed which, however, in order to be created, had to be cultivated by worthy officers and non-commissioned officers who were not always available.

In the war against the Prussians and their Italian allies the Austrians fought bravely. Under the worthy leadership of Archduke Albertus, they defeated the Italians at Custoza. Under the tragic command of Benedek – and thanks to the Prussian Dreyse rifles, they were decisively defeated at Sandova.