At Mainta in Calabria the British and French clashed once more during the Napoleonic Wars. There, once again, British supremacy was demonstrated, but also the horrors of war were demonstrated through the men's personal stories.

At first light on the 4th of July 1806 the two opposing forces moved against each other. Both moved staggered with the French general Rainier commanding his left, the Comberet brigade. And the British commander Stuart, however, had ordered the staggered movement of forces with Kempt's brigade forming his right flank.

Kempt, whose force was further forward than the rest of the British line, ordered his Sicilian and Corsican (Napoleon's opponents) skirmishers to deploy in skirmish formation in front of the main body of his brigade.> So it happened. Soon, however, they found themselves in front of a large number of French snipers and were forced to retreat.

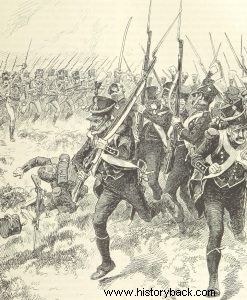

Kempt then ordered to reinforce his skirmishers with two more companies and the French retreated in turn. Immediately the British colonel gathered his divisions and regrouped them by deploying them in a line of two yokes. The French 1st Light Infantry Regiment (SEP), at the same time, deployed its two battalions (a total of about 1,800 men) in assault phalanxes and advanced.

“We stopped, formed a line and then advanced. It is impossible to describe how steadily we marched. At that moment I was on the right, about 10 m in front of our light infantry. The French marched upon us with speed. Suddenly they began to launch continuous volleys against us. But their fire either hit the ground in front of us, or passed over our heads without harming us.

"When they reached a distance of about 100 m. the order was given. Colonel Kempt shouted:Alt! You have left a lot of money. As soon as the order was executed he shouted again:Forward! We moved forward and then heard the order:Fire! , says eyewitness British artillery captain Thomas Dannelly.

The British raised their muskets and fired from a distance of 140 m. A few French fell but their advance did not stop and they continued to close. When they reached a distance of 75 m from the British line they received a second volley which caused them significant losses. Brigadier General Cabret who was in charge of them was wounded but remained at his post leading his men.

As the French approached the British positions they listened in amazement only to the orders of the British officers. They saw a living, motionless, "wall" of redcoats waiting for them with their muskets pointed at them. When they got within 20 m the British guns thundered again.

"Our men "held" their fire until the last moment and then engaged the enemy. The French put it to their feet, but only the fastest escaped the bayonets. All the rest were killed, wounded or captured. Bonaparte's 1st Regiment was torn to pieces," Dannelly reported.

From such a short distance musket fire was not only devastating, but literally tore opponents to pieces. It is not difficult to perceive the psychological effect which the sight of open skulls, spilled brains, severed hands or feet, torn by crushing wounds of the bodies of their fellow soldiers had on the French soldiers, who could not stand, but fled.

These were the right conditions for British bayonets. At least 300 Frenchmen fell victim to them, as immediately after the bombardment the British rushed out. When British Lieutenant Sandham later visited the makeshift hospital set up after the battle he was surprised to find that the vast majority of French wounded prisoners being treated had bayonet wounds mainly in the back and ribs. The French regiment was literally annihilated and Brigadier General Cabret was captured.

The battle of Maida finally ended in British triumph. French losses were particularly heavy for such a small-scale battle (about 5,200 soldiers per side). The dead reached 490, the wounded 870 and the prisoners 722. The British had only 45 dead and 282 wounded.

The French 1st SEP "breaks" as it receives the attack by the British lance after the homobrondes.