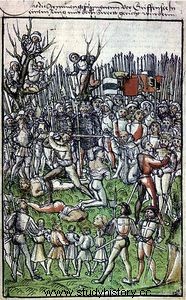

The Skinners are 15th century armed troops, sometimes confused with the 14th century Great Companies. They are war contractors who practice looting, ransoming, but also the customary forms of medieval warfare (siege, defense of strongholds, battles, rides) for their own profit and for that of Charles VII, to whom they claim to belong. .

Distinction between Flayers and Rovers

From the middle of the 14th century, the French royal troops, whether summoned or volunteers, were all pledged. The permanence of the conflicts during the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) therefore created war careerists, paid by the king or the great lords. These are not, however, mercenaries, because their vassalic and patronage ties remain in parallel with their economic interest in the war. During periods of peace or truce, these unemployed warriors gather in bands and live on looting and ransoms. In the 14th century, after the Peace of Brétigny-Calais (1360), the armies found themselves disbanded on the spot and their members broken off from their wages. Those who did not have the financial means to return home or wanted to continue their martial way of life (highly remunerative) then formed autonomous bands of truckers who exerted pressure on the regions of France:these were the Grandes Compagnies. They should not be confused with Les Écorcheurs, who were more the result of the political instability of 15th century France than of peace and were not mercenaries in the strict sense of the term.

The Kingdom of Bourges and the Flayers

The Ecorcheurs emerge in the context of the civil war (1411-1435) and the very limited political power of the Dauphin Charles after the Treaty of Troyes in 1420. The fluidity of allegiances and the fact that everyone can claim Armagnac or Burgundian parties push the emergence of autonomous armed groups which wage war “on their own terms”, according to profit prospects and their membership of a party (English, Burgundian, Armagnac). The war is then an extremely fragmented reality in a general disorganization, made up of very numerous small captains and territories with shifting allegiances.

The financial weakness of Charles VII during this period pushes him to hire and reward the autonomous captains who are loyal to him and claim his authority, without providing for them neither wages nor watches and accepting that they live on the country since he can't pay them. These men of war then quickly obtain an execrable reputation and are called the "Flayers" by the population. These occasional troops accumulate the problems for Charles VII:looters, undisciplined, endowed with strong leaders having a greater authority than his on their men, the Skinners are basically composite troops that the king gathers for lack of anything better. They are, however, capable men of war who lead a flexible group of men. The fidelity of the Skinners lies in one-off rewards from the king (money, offices) and in their personal allegiance to the king's party (the Armagnac party). However, they did not hesitate to serve other lords in accordance with their loyalty (La Hire, Poton or Dunois never betrayed the king).

A good example to understand the specificity of the Flayers is the case of La Hire, since the rewards granted to him by Charles VII follow his career as a Flayer. In 1420, he defended Crépy-en-Valois on behalf of the Dauphin; in 1422 he made him his captain (without however hiring him); in 1425 he was appointed equerry of the king's stable; in 1429 bailiff of Vermandois. This career as a royal officer shows all the ambivalence of the Ecorcheurs:even though they live in the country of looting and ransoms, they are much less disbanded than the truckers and do not only serve their interests, but are linked to a gone.

Integrate the Skinners into the standing army

After the Treaty of Arras (1435) which ensured the alliance between Charles VII and Philippe le Bon, the Ecorcheurs became undesirable for the king, who was concerned with regaining the favor of the provinces which he took back from the English (Paris was taken over in 1436, for example). To get rid of them, Charles VII instructs La Hire to gather the main companies of Skinners and take them to plunder outside the kingdom, in the Duchy of Lorraine.

At the same time as this separation, Charles VII tries to structure his army by selecting Flayer captains who will become royal captains, and by formally prohibiting others from practicing looting and ransoming in France. A first attempt, in 1439, was aborted because of the Praguerie:the great vassals were opposed to this reform which would take away the possibility of hiring the Skinners themselves. After the Franco-English truce, Charles VII managed to impose his reform in 1445, which directly concerned the Skinners. The (lost) ordinance of 1445 proclaims a general amnesty for all soldiers, the dismissal of all captains hired by the king or his vassals, and the rehiring of fifteen of them, retained directly in the service of the king. These fifteen Skinners made captains lead fifteen permanent companies of ordinance (each includes 100 spears provided or, theoretically, 600 men).

This transition works well and the Flayers, deprived of all legitimacy in a context where the power of the king is strongly reaffirmed and where a structured army is able to fight them, disappear with the reform of the army.