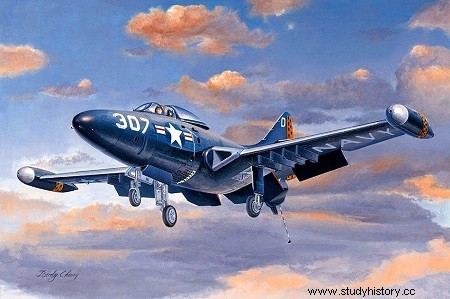

In the early months, the Allies used a motley assortment of aircraft, mostly remnants of World War II. The tracks were generally covered with pierced steel sheets placed on a more or less flat surface; these plates left dangerous holes and stones, which often punctured the tires. The average length of these tracks was 1500 m. Operating aboard jet fighters in such conditions posed tricky problems. Their weight generally exceeded that of conventional aircraft, by nine tons against five. Their tires, inflated to greater pressure, were more at risk of bursting. The landing or take-off speed was also higher, on average 250 km/h against 200, and the first jet engines gave less power on take-off than the large piston engines.

To have access to o greater power at take-off, some jet aircraft received JATO rockets (Jet Assisted Take-Off) fixed under the fuselage, and jettisoned after use. This solution did not simplify the problems of logistics and supply. Finally, the main concern remained fuel consumption at low altitude. The Jets had been designed for combat at 10,000m; but in Korea, they had to operate 300 m above the battlefield, and sometimes less.

Discussions took place at the Pentagon; it was necessary to define a modern aircraft, better adapted to these close tactical missions. The U.S. Navy would have wanted a machine with double turbine, fast and having a great autonomy, able to use rudimentary grounds. In fact, no such machine was built. The best answer to the problem encountered in Korea was found by engineer Ed Heinemann, of Douglas, who designed a small, simple and extremely strong jet aircraft, the A-4 Skyhawk. This device could not intervene in Korea; the war had been over for a year when he appeared! So the campaign continued with a mix of propeller planes and Jets, each of which had specific weaknesses.