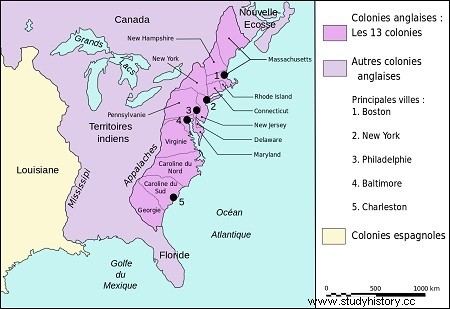

The Thirteen British (originally English) colonies were formed between the beginning from the 17th century and the first third of the 18th century, over several hundred kilometers along the Atlantic coast (see map). Their geography, their population, their economy and their institutions were then marked by differences. Communications between the settlements were slow and often difficult:the existing roads were in poor condition and there were few bridges.

People

Around 1770, the total population of the Thirteen Colonies was approximately 2.2 million. Since their foundation, the colonies have experienced strong population growth linked to immigration but also to a high birth rate. The population density was relatively low. For the most part, the settlers lived in the countryside and the population was concentrated on the coast where the main cities were located, of which Philadelphia was the most populous (about 45,000 inhabitants in 1780), surpassing Boston or New York.

Company

American colonial society was diverse:alongside the British majority lived Germans, Swiss, Dutch, Irish, Scots, Scandinavians and French, especially in the northern and central colonies. For the historian Fernand Braudel, this ethnic mixture would have favored the separation with Great Britain. Religious practices also varied:if the elites were of Protestant faith, they were divided into several currents. Jews and Catholics, who aroused suspicion, formed the main religious minorities.

On the eve of the American Revolution, settlers of European descent belonged to different social groups. If the seigniorial and feudal system was almost absent from the thirteen colonies, another hierarchy, based on land ownership and fortune, existed. The elite was made up of governors, planters, large merchants and shipowners. Then there was a category of craftsmen, representatives of the king, farmers and small traders:these middle classes represented 40% of the total population.

Sailors, tenants and servants occupied the bottom of the social ladder. The indentured servants (called "engaged" in New France) constituted a white sub-proletariat whose condition was close to that of slaves:they were prisoners, women and children sent willingly or by force to populate the New World and work in agriculture.

From the colonial era, social gaps widened. The various groups of settlers expressed divergent interests which caused tensions, even revolts in the cities and the countryside. Enlightened elites were concerned with maintaining social order and protecting their properties. Other settlers suffered more from British tax measures and land inequalities. Social tensions were stirred up by the action of certain preachers and relayed in places of urban sociability:taverns and inns were places of information, debates and meetings. The press also played an active role in the revolutionary fermentation.

The numerical importance of African Americans was notable:between 1750 and 1780, their number rose from 236,000 to 575,000. Most blacks were concentrated in the southern colonies and were slaves. However, a minority of freed blacks lived in the cities. Within the limits of the American territory of 1790, the number of Native Americans is estimated between 100,000 and 200,000 people.

Hannah Arendt, based on the testimonies of European travelers of the time, believes that if in the United States, poverty existed, on the other hand the misery so frequent in Europe then practically did not exist there. For her, this point would partly explain why the American Revolution was so different from the French Revolution of 1789.

Government

Each colony had its own political status which depended on its history. Three categories were usually distinguished:chartered colonies were regulated by charters granted by the sovereign to private shipping companies. The foundations of the colonies of owners rest on the initiative of a great character, the Lord Proprietor. The citizens chose their governor there. Finally, the colonies of the crown (or royal colonies) benefited from a constitution drawn up by the royal power.

The governors exercised executive power in the name of the king and disposed of the armed forces. They were assisted by customs officers or even royal revenue investigators. The Governor's Council had judicial, administrative and legislative powers. Equivalent to an upper house, it had an advisory role. Finally, each colony had an assembly which discussed and settled local problems, but also the budget and the equipment of the militia, with the agreement of the council. She could send agents to present petitions and requests in London. Town meetings in Massachusetts allowed settlers to exercise a form of direct democracy. The remoteness and vastness of the colonial territory allowed the Americans to have relative local autonomy.

Economy

The thirteen colonies formed an economically prosperous whole. To the north, New England lived on crafts, maritime trade and fishing. Boston merchants traded with the West Indies:they exported wood, flour, fish, whale oil and imported sugar, molasses, tafia. This trade stimulated metallurgical and textile production, as well as allowing the development of shipyards and distilleries.

In the colonies of the centre, agriculture was diversified and animal husbandry omnipresent. Marked by a humid subtropical climate, the southern colonies lived essentially from a dynamic commercial agriculture (exports of tobacco, indigo and cereals mainly). The planters used slave labor who worked on large farms. The white aristocracy lived on these estates and had beautiful mansions built. However, the plantation system was not yet the same as that which would last until the Civil War, the latter being imported by French owners fleeing the slave revolts in 1798. The South was mainly rural and the cities were rare and relatively sparsely populated (Charleston, Baltimore and Norfolk).