Of the peculiar diplomatic relations, apparently cordial, that the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany had in the 1930s, in the run-up to the Second World War and even when it began, one of the most surprising examples is the transfer of the former to the second, a naval base for its navy that would allow its submarines to be supplied in the North Atlantic. It was located on the Kola Peninsula, one end of the Zapadnaya Litsa Fjord, in Murmansk Oblast, which borders Finland and Norway, and was called Basis Nord. Today it is the base of the Russian Northern Fleet.

Soviets and Nazis seemed to have resolved their ideological and national differences on August 23, 1939, when their respective foreign ministers, Viacheslav Molotov and Joachim von Ribbentrop, signed the non-aggression treaty popularly known by their surnames. Perhaps the world would be amazed but they were not fooling themselves and they knew perfectly well that they were only postponing an inevitable confrontation that at that moment was not good for any of them; to the Nazis, because they had more immediate objectives; to the others, for the same reason and because their army was still in the process of modernizing itself after decades of not being able to do so due to the civil war.

However, the pact gave both what they needed:time to implement their respective plans and the guarantee that the other would not interfere in them. That allowed Hitler to launch himself into the western part of Poland, starting de facto World War II nine days later. Two weeks later Stalin did the same with the eastern one (since, after a previous aggressive expansionist stage, it included territories of Belarus and Ukraine that the Soviets claimed as their own), as well as trying to recover Finland, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania and Bessarabia. An annexed secret protocol established the respective zones of influence in Eastern Europe and, indeed, the Wehrmacht and the Red Army came to fraternize and parade together on the Polish border.

The conditions were sown to extend this apparently idyllic collaboration to the economic area, since shortly before the signing, on August 19, a commercial treaty was also agreed that involved the exchange of German war material for the obsolete Soviet forces in exchange for the supply of raw Materials. As at the end of 1939 everything seemed to be going well (Germany refrained from the so-called Winter War against Finland), the Soviets agreed to a request that Ribbentrop had made:the transfer of a naval base on Russian soil for the submarines operating in the North Atlantic.

Stalin gave the go-ahead but with two conditions. The first was that it could not be the port of Murmansk, as the others requested, because at that time the Soviet Union was a non-belligerent country; the second, also related to that, which had to be kept strictly secret so as not to have a diplomatic conflict with other nations. So a place located to the west of that city was chosen, but the Germans considered it unsuitable due to the precarious facilities it presented, so that the solution finally chosen was the aforementioned Basis Nord in Zapadnaya Litsa, which is one hundred and twenty kilometers from Murmansk. and has access to the Belomorkanal (White Sea-Baltic Canal, a canal opened in 1933 that connected those two seas with each other and with Lake Onega).

In reality, that site was even more precarious than the other, but precisely because of this and because it was inside a fjord, invisible from the sea due to hundred-meter-high cliffs, surrounded by Russian soil and closed to navigation by third parties, it was discreet enough to go unnoticed by the enemy. It would not do it completely, of course, which would be fixed with possible setups suggested by the Soviets themselves:their supply ships could simulate being assaulted by the U-boats (and once the supply was done, be released) or leave their supplies in a previously agreed point.

The Teutonic naval attache gave the go-ahead and planning work immediately began, as Rear Admiral Karl Donitz, the befehlshaber der U-Boote (commander of the submarines) wanted to dispose of Basis Nord as soon as possible. In fact, he expected it to be available by the third week of November; however, wishes are one thing and reality is another. In the first place, the Kriegsmarine did not consider it so urgent and in the second place, the Soviets ceded the base but added a thousand and one bureaucratic obstacles to those that already existed for its implementation:isolation by land, lack of facilities, absence of a network railway or highways and even lack of drinking water.

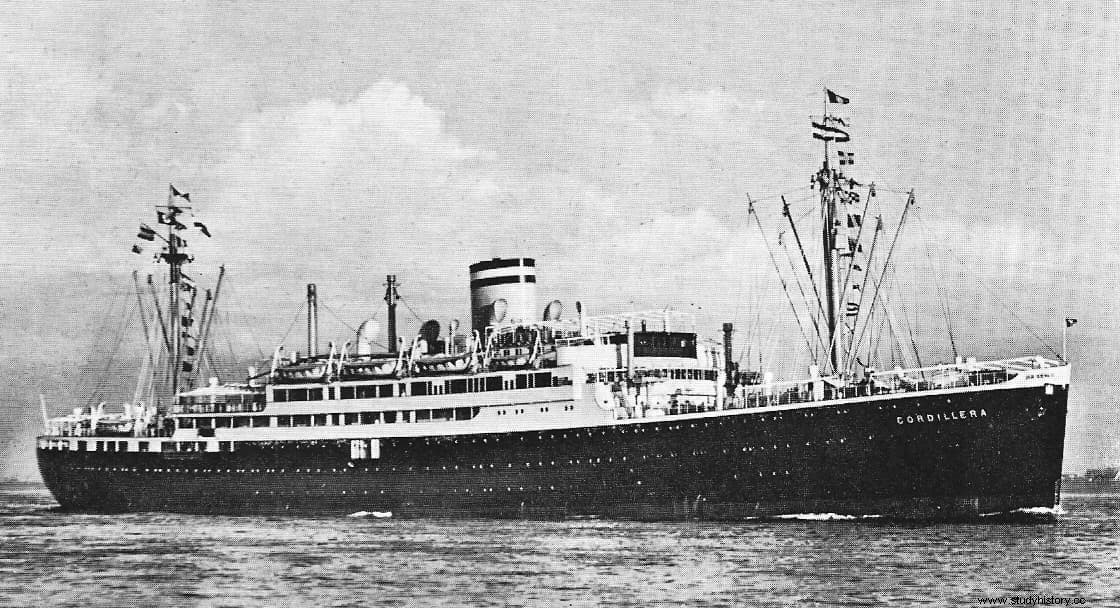

Even so, the Germans chartered several merchant ships loaded with fuel and other necessary supplies to send them from Murmansk, where they had been interned since the beginning of the war, to Zapadnaya Litsa and be able to supply the submarines. Two were HAPAG (Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft) passenger ships called Phoenicia and Cordillera , and the third was the Sachsenwald , a trawler converted into a weather ship. The poor conditions that the fjord had for large ships, together with the bad weather, meant that the three ships had to leave soon.

The relay was taken by Jan Wellem , a whaler converted into a freighter that sailed from Kiel, arriving in February 1940. A further HAPAG unit, the St. Louis (which had the curious story of having transferred a thousand exiled German Jews to America and narrowly avoided internment in New York), something that was reinforced by the arrival at the end of February of another adapted whaler, the Wikinger V , so between all of them they transported abundant supplies to Basis Nord and it was well stocked to finally start supplying the U-boats, with the permission received from Moscow, before spring came.

But it couldn't be either. Despite the secrecy employed, rumors of a German base in the Russian north had been circulating since December 1939, and the Danish and French media even reported it publicly, although they did not know the exact location. Germany hastened to deny them, but if confirmed, the great victim would be the Soviet Union, since it feared an intervention by the British in the Winter War (the invasion of Finland), which had made it very difficult for the Soviets in the face of the unexpected and tenacious resistance from the Finns.

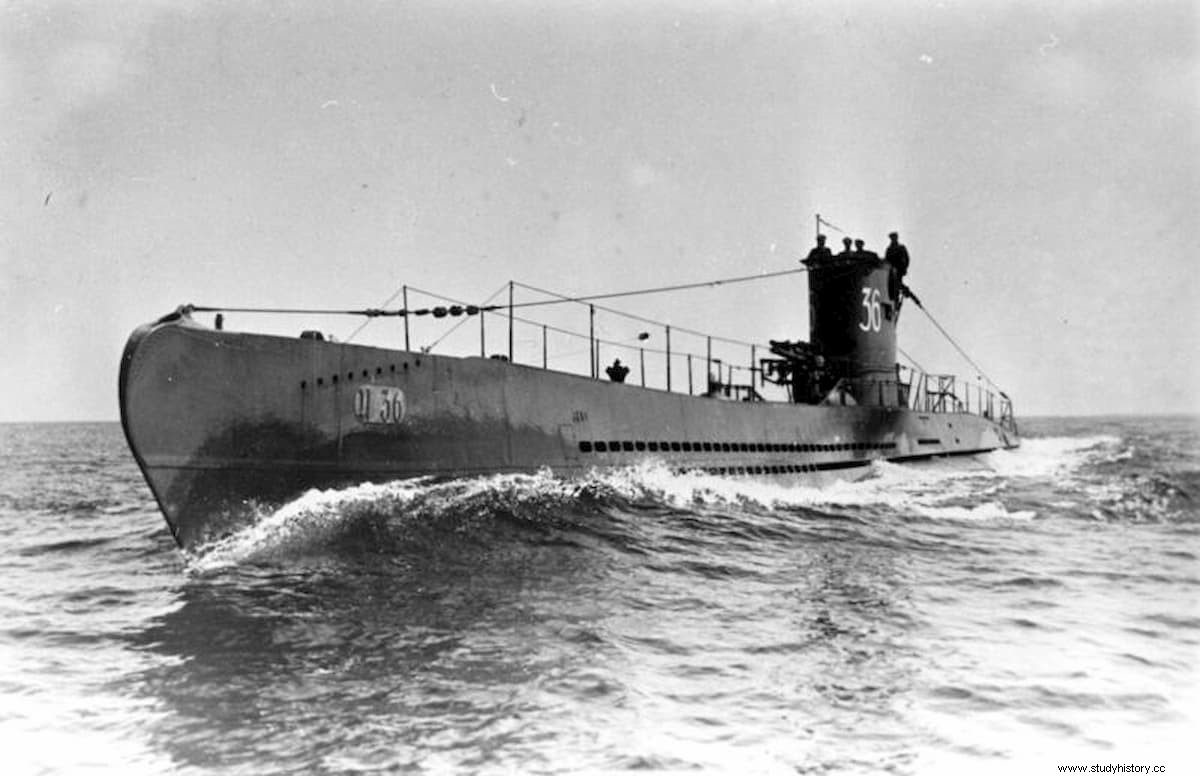

In fact, the Kriegsmarine had sent the first two U-boats to explore Basis Nord in December:U-36 and the U-38 , led by Wilhelm Fröhlich and Heinrich Liebe respectively. The first hit an unexpected snag:it was still in the Norwegian Sea, near Stavanger, when it was intercepted by a British submarine, HMS Salmon. , who torpedoed it and sank it with her forty crew members. Instead, the U-38 she rounded the North Cape and made the trip without incident, cruising the fjord in silence to pretend the Soviets knew nothing (although in fact they had warned of her presence by coded message).

That is why in March, when the Swedish press also echoed the possible presence of German submersibles, the Soviets suggested that they move the base to Yokanga Bay. It was the mouth of the homonymous river, located three hundred kilometers to the east and, therefore, much further from the prying eyes of reconnaissance planes. But if it was far away for some, it was also far away for others and the Kriegsmarine rejected the proposal, although in reality it had other more compelling reasons for not being interested.

And it is that on April 8 Germany began Operation Weserübung, that is, the invasion of Norway. His goal was twofold; On the one hand, to ensure the importation of iron from Sweden through the port of Narvik and, on the other hand, to have a solid base so that the Luftawffe could launch its air raids on Great Britain. In this last sense, Norway was also a good starting point for the planes to cover the possible start-up of the projected Unternehmen Seelöwe u Operation Sea Lion, that is, the conquest of the British Isles. In any case, having the Norwegian territory allowed many more possibilities to supply supplies without having to go to the Zapadnaya Litsa fjord or, more importantly, depend on the Soviet Union.

In fact, Basis Nord ceased to be used, remaining only as a symbol of a fictitious friendship that was doomed to break. In total disuse, the Phoenicia , the last remaining ship there, set sail in mid-June 1940 and in September the großadmiral Erich Raeder, commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine, resigned from Basis Nord in a letter to Admiral Nikolai Kuznetsov, head of the Soviet fleet, thanking him for his cooperation. In less than a year, Germany would undertake Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the USSR.