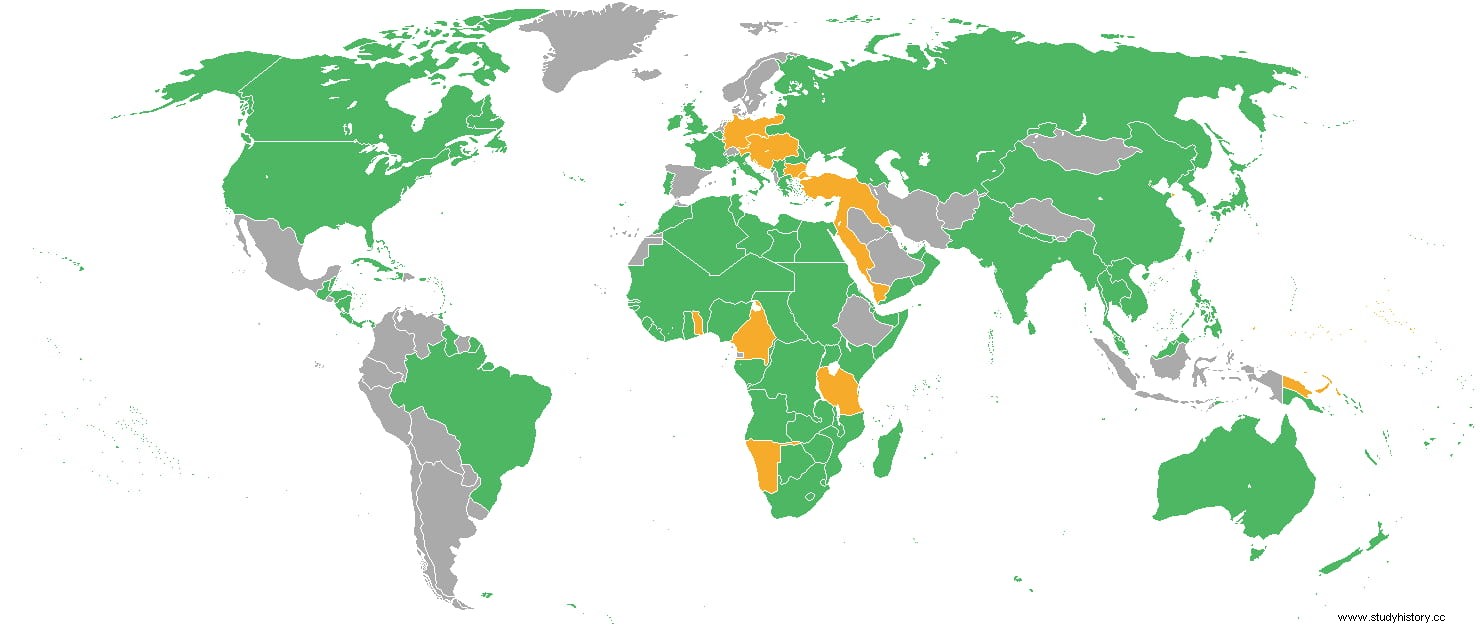

The First World War does not receive that name for its own sake, nor is it a hyperbole. No less than 38 countries from all continents officially participated in that contest, that is, they proclaimed themselves belligerent:twenty of them allied (plus another 9 that supported them without participating militarily) by 22 of the central powers.

More or less because some had a peculiar patronage status (emirates, sultanates...) and others were integrated into supranational formations. Today we are going to take a look at the role played by the Siamese Expeditionary Forces.

Siam was the name that Thailand had until 1939, when it was changed to Prathet Thai (Free Country), which a decade later was changed again to the current one in allusion to the majority national ethnic group, the Thai. In 1914 it was a kind of buffer state between French Indochina and the British possessions of Burma and India. In fact, Siam had a curious characteristic:it was not and had not been a colony -in fact, it was the only country in Southeast Asia that was not-, although it was considered akin to the British Empire.

The outbreak of war led many of these small nations to align themselves with their big sisters, but it was one thing to show solidarity or even join the allies and another to contribute troops. For example, China, Costa Rica, Cuba, Guatemala, Liberia, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama, in chronological order, joined the allied cause and even declared war on Germany but without intervening.

On the other hand, if other a priori surprising countries like San Marino, Brazil or Nepal took up arms; the Kingdom of Siam did too, the only one in the area that entered of its own free will.

The main reason for this was to demonstrate to the world the degree of development that had been reached and King Vajiravudh's commitment to international law. Of course, there were also purely strategic factors, such as being in an advantageous position in the face of a hypothetical post-war distribution and thus recovering the territories that it had lost to the colonial powers between 1889 and 1909 (Laos, Cambodia and its four southern provinces), but nothing more, since Siam was very far from the area of influence of the Germanic colonies in that part of the planet.

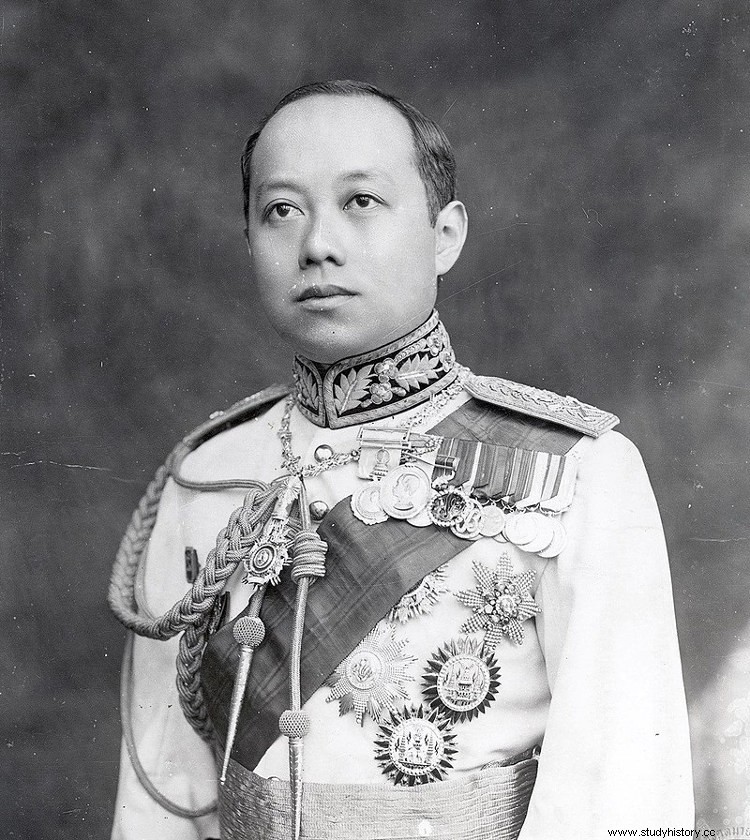

Vajiravudh was the son of the prestigious Chulalongkorn, a monarch who had made history by modernizing his kingdom through a reformist policy that included the abolition of feudalism and slavery, modern administrative restructuring, the introduction of the railway and an updated monetary system, the implementation of religious freedom, the adoption of the Western calendar, the promotion of education through the creation of schools, the construction of public hospitals, etc. Here we know him, above all, for having studied under the supervision of an English governess named Anna Leonowens, a relationship that made cinema popular.

His heir, who had ascended the throne in 1910 under the name of Rama VI, therefore tried to continue this work and therefore sided with the allies, seeking to strengthen his position with his subjects to be at the height of his father and recover its strength after the attempted military coup suffered in 1912. It is said that he made the decision following the French government's suggestion that the Siamese living in Europe, most of them students, be in charge of driving ambulances and other supply vehicles, as well as being able to access flight schools to be pilots or mechanics. Always in a volunteer situation, not by obligation.

The fact is that Rama (or Vajiravudh) accepted the proposal and on June 22, 1917 declared war on the German and Austro-Hungarian empires, expelling the citizens of those countries who held positions in the Railway Department and the Siam Commercial Bank. , in addition to confiscating their boats and properties.

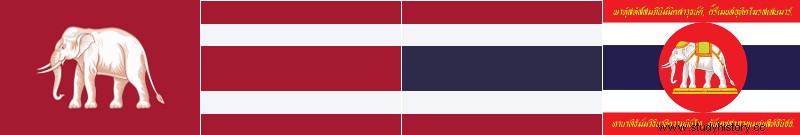

He even changed the flag, replacing the one with red and white horizontal bands, introduced in 1916 instead of the classic one designed by his grandfather Mongkut (crimson with a white elephant), for the current Thong Trairong (Tricolor), although a mixed one (tricolor with elephant) was brought to Europe. All this inflamed the nationalism of his people, just as he intended, favoring the support of public opinion for entering the war.

However, theory was one thing and practice another. Siam could have taken giant steps in modernization but its army was far from being prepared to face a conflict like this. First, due to its material deficiencies, almost without artillery, vehicles and other equipment; second, due to the lack of experience in these matters and even less in a climate and landscape as different as the European one. On the other hand, if it had well-trained officers in modern warfare and an air force practically unique in its latitude. The limitations of aviation at the time meant that the Siamese were not far behind in that regard.

The majority of the people enthusiastically endorsed the king's decision and his rule. There was hardly any opposition to the declared warmongering and the little that was manifested in that sense did so rather by leaning towards the other side, thus repeating the dichotomy between alliedophiles and Germanophiles that existed in the neutral nations, although the Buddhist religious establishment was also opposed. . However, the ad hoc appeal The war ministry made in September 1917 only asked for volunteers and with those who showed up, a body of 414 aviation mechanics and another of 870 drivers, mechanics in general, sanitary and other auxiliaries were formed.

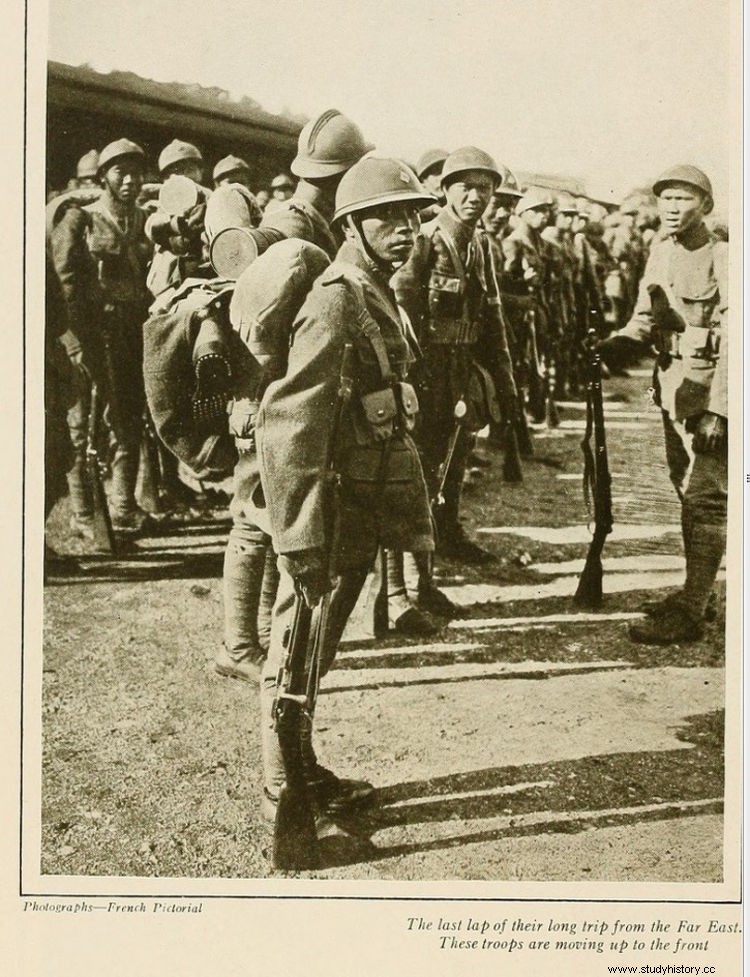

The organization of the expeditionary force, with its corresponding training process, vaccinations, etc., lasted several months. On June 20, 1918, the expeditionary force embarked for Marseilles aboard the S.S. Empire, being seen off by a vibrant crowd. They were 1,284 men under the command of General Phraya Phya Bhijai Janriddhi, a military veteran born in 1877 and educated in Belgium and France who naturally spoke French. After calling at Singapore, Colombo and Port Said, the ship reached her destination in five weeks.

The contingent was received by Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and even by the British King George V, who thus cleaned up the mistakes made at the beginning:one was to believe that those newcomers were soldiers recruited in Indochina; the other practically ignored them while, at the same time, paying attention only to the American troops, who were also landing in France on those days. The aviation contingent was then sent to the Istres, Le Crotoy, La Chapelle-la-Reine, Biscarosse, Piox, Avord and Pau airfields; transport, to a camp in Lyon for two more months of practice, to move to the front.

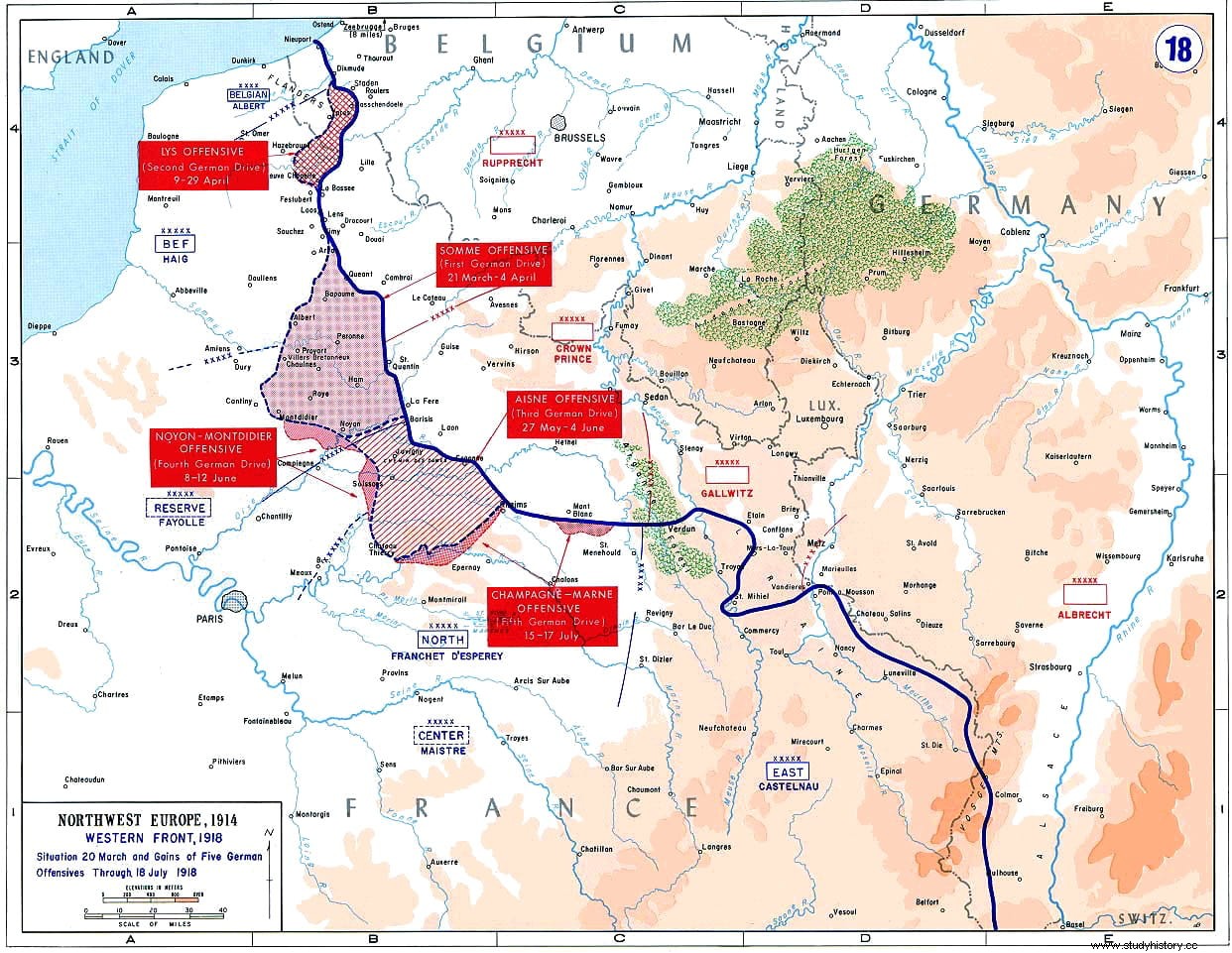

A first detachment led by Phya Bhijai Janriddhi was assigned at the beginning of August to swell the troops that were going to stop the German offensive by fighting the so-called Second Battle of the Marne. In mid-September, the remaining members of the motor transport corps headed for Champagne and Meuse-Argonne, operating in the vicinity of Chalons. The aviators, on the other hand, needing more training time, would not finish it in time to be able to get on the planes and face the enemy.

As expected, cultural differences led to tension between the Siamese and the French liaison officers, which boiled over on the battlefield:communication problems due to insufficient interpreters and the superior attitude of the Gauls, who tended to ignoring their Asian counterparts to address the troops directly, they ended up exploding and even jumped into the diplomatic arena to the point that the Siamese government considered ordering the return of their own.

It was not necessary because on November 11 the armistice was signed and that relaxed things. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs then saw the opportunity to solve this unpleasant situation by including the Siamese transport corps among the occupation troops that entered Germany.

He hit the jackpot; the Siamese were flattered and the king himself expressed his pride on the day his soldiers set foot on German territory, presenting himself as a warrior king who had united the country in a common cause. The expeditionary force was quartered in Neustadt, Rhineland-Palatinate, in December 1918 and remained there until July of the following year, in which month they participated in a series of victory parades held in Paris, London and Brussels to the delight of the court. and the Siam executive.

The return to Siam was made in two phases. First did the aviation corps, which did not take part in any combat and arrived in Bangkok before those parades, in May. The others did so in September and upon arrival they found a tremendous welcome, with four days of national holidays and official splendors that included homage to the fallen in temples, plus the erection in 1921 of a public memorial in their memory in the center From the capital.

There were not many casualties, due to the work carried out and the fact that they barely spent a month at the front; none from enemy fire:19 dead, half from accidents and the other half from the flu (the European winter was very harsh for people accustomed to tropical weather).

The soldiers, who were awarded the Croix de Guerre, were awarded by the king with the Order of Rama. Siam thus earned the right to a seat at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and, therefore, was one of the founding countries of the League of Nations (an organization that should monitor peace and international relations to avoid a new war) , but did not recover the lost territories and had to settle for the adjudication of several German merchant ships.