When Cleisthenes established democracy in Athens, practically inventing it between 510 and 508 BC, he also wanted to provide the people with a method with which to prevent a tyrant from regaining power in the city.

That instrument was the law of ostracism, by which those citizens whose actions or ideas were considered dangerous or harmful to the survival of democracy and popular sovereignty could be condemned to exile.

Thus, each year between January and February approximately the citizens' assembly voted and decided whether to proceed to ostracism. If the vote was positive two months later they met again and, if there was a quorum of at least 6,000 voters, each one wrote in an ostracon (ceramic fragment) the name of the one whose banishment seemed necessary or appropriate.

If any of the citizens mentioned in the popular votes reached an absolute majority, they were exiled for 10 years, and had to leave the city within a maximum period of 10 days. He did not lose his rights as a citizen, and there was even the possibility of being pardoned by a new vote, as happened on several occasions.

But as often happens, what was initially a tool for defending democracy ended up becoming a political weapon between factions. It was first used in 487 BC. to banish a relative of the tyrant Pisistratus (who had ruled Athens between 561 and 527 BC) named Hipparchus.

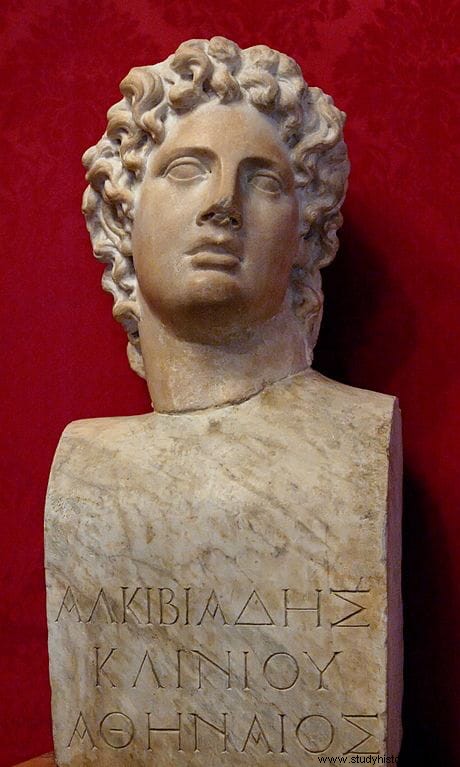

In total, 12 ostracisms are known to have been practiced between 487 and 440 BC, including Megacles (486 BC), a nephew of Cleisthenes himself; Callixenus (485 BC), probably also a nephew of Cleisthenes; Xanthippus (484 BC), father of Pericles; Aristides the Just (482 BC); Themistocles (471 BC), the politician and general who led the Greek army at Salamis; Cimon (461 BC), the son of Miltiades the victor at Marathon; Alcibiades (460 BC), grandfather of the later and more famous Alcibiades; Meno (457 BC); Callias (445 BC), who had fought at Marathon dressed as a priest; Damon (443 BC), musician and teacher of Pericles; and Thucydides (442 BC), the political opponent of Pericles.

After the year 442 B.C. ostracism fell into disuse. Obtaining a quorum of 6,000 citizens was becoming more and more complicated, and soon other less harsh and faster methods of a legal nature emerged to eliminate political opponents. And not just one a year, but several at the same time.

But 26 years later, the method of ostracism was resorted to for the last time. It happened in 416 B.C., and the exile, who would therefore be the last to suffer said punishment, could be said to backfire .

His name was Hyperbolus and he was a manufacturer of oil lamps. He entered politics opposing peace with Sparta after the first phase of the Peloponnesian War. The playwright Aristophanes presents him in his works as the man who controlled the Assembly of Athens, and most writers who mention him describe him as the leader of the masses , all with an evident ironic and contemptuous tone.

He was a skilled orator, possibly a trierarch (captain of a warship, which he paid for himself) and a wealthy man, whom the sources often accuse of being a demagogue. He wanted to lead one of the two Athenian political factions, but found that Alcibiades was challenging him for the position.

So it occurred to him to rescue the old practice of ostracism to get rid of Alcibiades on the one hand and at the same time his political opponent Nicias. According to Donald Kagan, for the last quarter of a century, it had not been used against anyone because the cost of such a sentence—banishment for ten years—was so high that only those with a secure majority could benefit from one. such an extreme measure. Since the days of Pericles, no Athenian politician had enjoyed such a degree of trust .

The support of Nicias and Alcibiades were very even and Hyperbolus thought that he could take advantage of proposing the ostracism of both, harboring the hope, according to Plutarch, that when one of the two men was sent into exile he would be the rival of the one that remained. . So he convinced the Athenians to resort to the method again after so many years.

What Hyperbolus did not expect was that Nicias and Alcibiades would come to an agreement, instructing his followers to inscribe his name on the pottery shards for voting.

Possibly this very unusual fact, that the exile lacked the support of an important part of the Assembly, made the method of ostracism useless, since in the end the leaders of the two opposing factions had gotten away with it. In fact, a short time later the Athenians again elected Nicias and Alcibiades as generals (strategos).

For his part, Hyperbolus, who had been exiled on the island of Samos, ended up perishing at the hands of the Samians during the incidents of the oligarchs' revolt, and went down in history with the bad reputation that Thucydides attributed to him:

Ostracism was never used again in Athens. It still existed and the issue was still raised every year in the Assembly, but they never voted for its use again. Up to 12,000 ostracon fragments have been found in the agora and in the Ceramic neighborhood. with registered names corresponding to the votes of the assembly.