The idea of a submarine facing a cavalry unit can be considered absurd, although it must be recognized that seeing something like that would be as memorable as it is bizarre. Without going so far, the First World War left us with a couple of cases that came as close to it as physically possible. One was carried out by the British submarine HMS E11 and another the German SM UC-61 , the latter with the result that her crew was taken prisoner by a squadron of French horsemen.

As its name indicates, the HMS E11 It was the eleventh submersible of class E (an improved version of D), of which fifty-six units were built. It was 55 meters long by 4.6 meters wide and displaced 662 tons (897 submerged), powered by two 800-horsepower diesel engines plus two 420-horsepower electric ones that allowed it to reach a maximum speed of 16 knots on the surface (10 underwater), with a range of 2,829 nautical miles (5,238 kilometers) and being able to remain submerged for up to five days, with a depth limit of 61 meters.

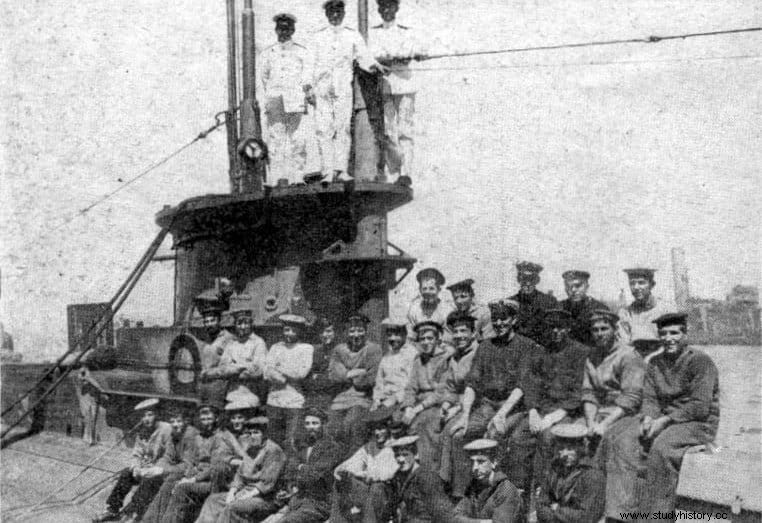

The E11 she was launched on April 23, 1914, and was assigned a crew of 28 sailors and three officers. Shortly after, in August, the war began and the following month she carried out her first unlucky action:she mistook the Danish submarine Havmanden (neutral, then) with the German SM U-3 and she fired a torpedo at him which fortunately missed its target.

In September, the Royal Navy commissioned Lieutenant Commander Martin Dunbar-Nasmith, a thirty-one-year-old Englishman who already had experience in the submarine force having sailed on HMS D4 , in which he had the honor of receiving King George IV on board when he expressed his desire to visit him.

The ship was first assigned to the Baltic and at the end of 1914 it participated in the defense of the port of Scarborough, in which it could not show off because its torpedoes were defective, although it later joined the attack against the zeppelin hangars of Cuxhaven (Lower Saxony) rescuing the shipwrecked from sunken own ships.

In May 1915 she changed the cold northern waters for those of the Sea of Marmara and that is where she began the legend of her, as she crossed the Dardanelles and captured a dhow (a traditional sailing ship) that he tied to her turret to attract prey. However, her imaginative trick did not work.

She then undertook a more classic campaign and there she did shine, sinking several smaller vessels (including a gunboat), the Turkish transport Nagara (carrying a shipment of ammunition) plus three other ships of the same type. In fact, the E11 she noted on her resume no less than 11 sinkings, some in a daring attack on the Golden Horn (the first in five centuries), which allowed Nasmith to win the Victoria Cross. On a second mission that summer, he expanded the count to 80, including the Turkish cruiser Peyk-i Şevket , to the battleship Barbaros Hayreddin (which was actually the German Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm , renamed by the Ottoman Empire after buying it in 1910) and the charcoal burner Isfahan .

Two of his officers, Lieutenants Guy D'Oyly-Hughes and Robert Brown, were also decorated for carrying out a ground raid to blow up the railway linking Constantinople and Baghdad. This brings us back to the beginning of the article, when we were talking about a confrontation between the submarine and the cavalry. In reality, the episode took place in the spring of 1915, just after the Nagara was sunk. , when a new torpedo hit another Ottoman transport and ran it aground off the coast.

It is possible that Nasmith only emerged to check the result of his action, but the fact is that suddenly a squad of horsemen appeared and he opted for prudence, leaving the place. Half jokingly, we could say that it was the first time that the cavalry put a submarine to flight. The fact is that it was not going to be long before something similar happened again and this time with direct interaction. It was July 25, 1917, a long way from where the E11 made his triumphant career:on the French coast of the Pas de Calais. And this time it was a German submersible.

It was, as we said before, theSM UC-6 1, an unterseeboot of the model II CPU, that is to say, the one used fundamentally as a miner, which does not mean that they were not also used to combat; in fact, the UC IIs have the best record in underwater warfare, with more than 1,800 ships sunk. The UC-61 She measured 51.85 meters long by 5.22 meters wide and displaced 422 tons on the surface (504 submerged). It reached a top speed of 11.9 knots (7.2 under water) thanks to two 600-horsepower diesel engines and two 620-horsepower electric ones, being able to reach depths of up to fifty meters and have a range of 8,000 nautical miles (14,800 kilometers) that in immersion were reduced to 59 nautical miles (100 kilometers).

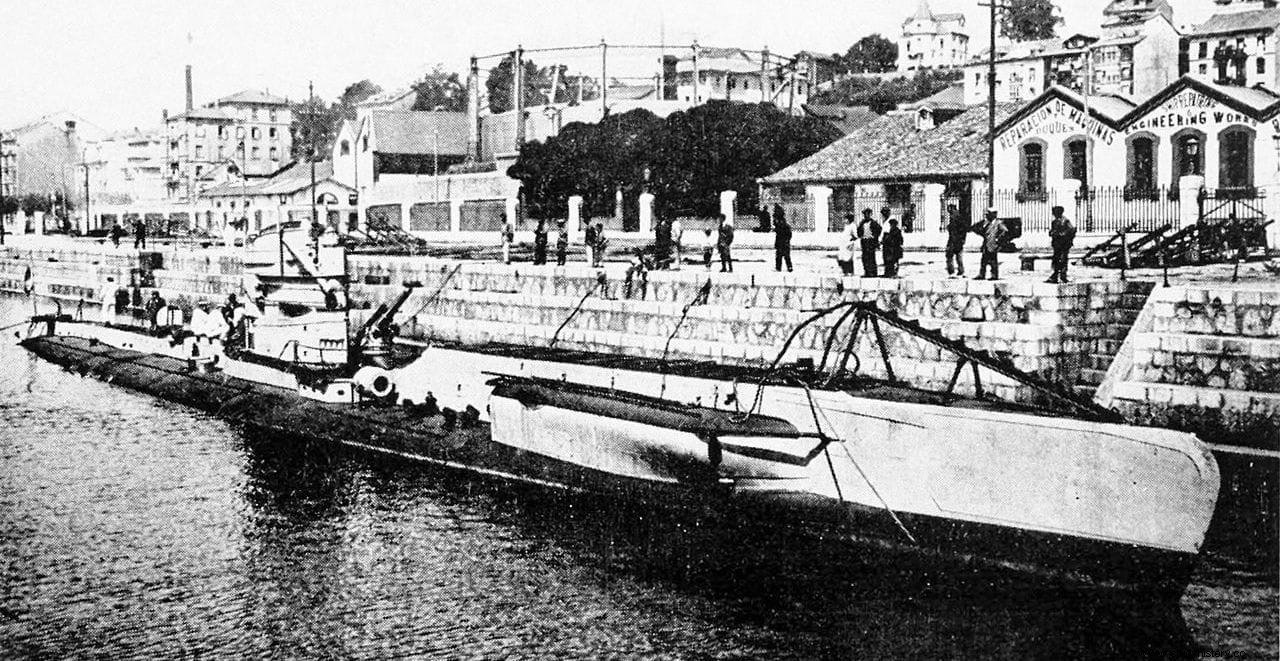

The UC-61 She was launched on November 11, 1916, and placed under the command of Lieutenant Captain Georg Gerth, who commanded three officers and twenty-three sailors. Attached by the Kaiserliche Marine a la Unterseebootflottille Flandern (Flanders Flotilla), her first mission proved short-lived, as she ran into a destroyer and had to descend about 60 meters to escape her charges. She succeeded, but at the cost of severe engine damage and having to return to port. After a month and a half of repairs in Zeebrugge, Belgium, she set sail again... only to get stuck in an anti-submarine net laid by the British and be forced to turn back once more.

At the end of June she finally managed to get out, laying some mines near the Pierre-Noires lighthouse that would cause the sinking of the French cruiser Kléber . She then camped wide of her, sending two steamers and three sailboats to the bottom, before returning to Zeebrugge with a dozen enemy sinkings on her record. From there she left on a new mission on July 25, transporting 18 mines that she had to place in the ports of Boulogne and Le Havre. Along the way he discovered a cruiser and Captain Gerth decided to follow it stealthily, waiting for the right moment to attack it, without imagining that this action would bring final misfortune to his ship.

And it is that that same night she passed too close to the coast and, without noticing the low tide, she ran aground near Wissant, in the Boulogne-sur-Mer district. The UC-61 she was hopelessly lost, so her evacuation was ordered, before which explosives were prepared in the tower to detonate her and prevent her from falling into the hands of the adversary. By then, her presence had already been detected by the French customs officers, who gave the corresponding notice. A section of cavalry was immediately dispatched, reaching the beach in time to watch the submarine blast apart, splitting in half; the Gauls took the crew prisoners.

Later, the remains of the German ship would be bombed to destroy the mines that she had on board and prevent them from being a danger to the population. Because although it is true that, little by little, the hull was being buried under the sand, it is also true that every two or three years, depending on the tides and the wind, it emerges -more and more- and becomes an attraction tour. Double interest, if we accept the defeat of the submarine weapon against the equestrian one.