Traditional historiography, especially Anglo-Saxon, establishes a manifest contrast between the Dutch school and a supposed “Spanish-German” school. Actually, it is possible to speak, rather, of three schools, the Dutch, the Spanish and the German , given that, as we observed in the previous chapter, the Spanish and German practices were different. The first conceptual error is to assume that the forces of the United Provinces had a much higher proportion of firearms, when in reality the ratio between pikes and arquebuses or muskets evolved in a similar way. The Army of Flanders was the first to increase the number of shooters . Already in 1578, Francisco de Valdés indicated in his Dialogues of military art that "usually there is much more arquebus than piquería in the Spanish infantry, to the extent that we see nine thousand infantry together and hardly have a thousand and five hundred pikes in such a large number, all the rest being arquebusiers".[1] In the German case, the Long Hungarian War (1593-1606) against the Ottomans, the imperial troops considerably increased their firepower:the thirty-three recruitment commissions studied by József Kelenik reflect a ratio between pikes and firearms ranging from 1:1.2 to 1:11, with an average of 1:2.[2]

Another basic error stems from conception of the formations of the Habsburg troops, whether Spanish or Austrian, and of the Catholic League, as large square masses with little mobility. Neither in the decade of the War of Flanders prior to the Twelve Years' Truce nor in the Long Hungarian War were infantry deployed in squads of thousands of men with forty or fifty ranks deep. The vanguard squadron that Ambrosio Spínola formed to rescue Groenlo in 1606 consisted of 1,200 infantry, of which 462 were pikemen, and had 33 rows in front and 14 in the background.[3] On the Hungarian plain, the Imperials used to deploy their squads 10 or 12 ranks deep.[4] Only the Swiss remained faithful to tradition and, at the Battle of Tirano (1620), during the Valtellina War, the Bernese came to form a squad of 3,000 men, which the Spanish harquebusiers and musketeers, sheltered behind stone fences and with the help of the unevenness and the vines that covered the land, they undid in just 15 minutes.[5]

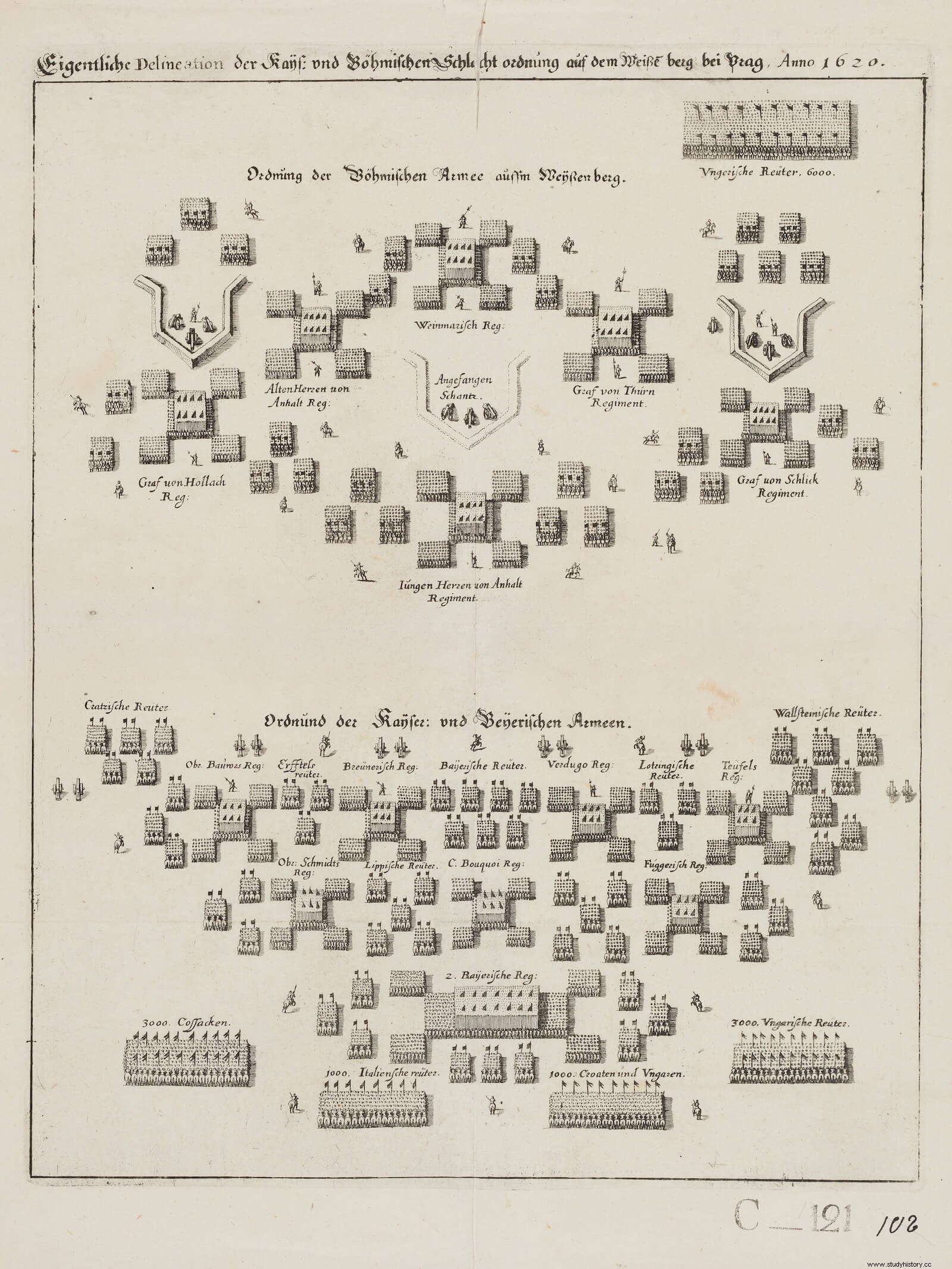

Another question is to what extent the German Protestant armies had adopted Dutch practices . In 1617 John VII of Nassau-Siegen founded a Schola Militaris in Siegen that trained many young Germans, mainly from the Calvinist territories, and was led by Johan Jacob von Wallhausen, a former United Provinces Army officer and one of the leading military theorists of the day. This, in addition to the presence, in the Protestant ranks, of former captains of Mauricio de Nassau –Dodo zu Innhausen und Knyphausen, chief of staff of Christian de Brunswick, is the clearest example–, has led multiple authors to assume established that the Protestant Germans fought on the Dutch model. In fact, there are indications to the contrary. The contemporary relationship of the Mercure François describes the Protestant order of battle at White Mountain (1620) as conservative:“[the Elector Palatine] had deployed at the head of his army the Regiment of the Prince of Anhalt in a large square battalion with its sleeves at the four corners (as were also the other five regiments).”[6] In his account, the real Protestant command, Anhalt, makes it clear that "the enemy formed in order at the foot of the mountain and partially behind it in the same way as us."[7] In subsequent battles, the Margrave of Baden-Durlach, Ernst von Mansfeld and Christian of Brunswick relied on their cuirassiers, while the role of their infantry was very poor, with few exceptions such as the Saxe-Weimar regiments. At Wimpfen (1622), Baden deployed his battalions behind a circle of wagons; As for Fleurus, the Walloon officer Louis de Haynin recounts that Mansfeld “had placed his three large infantry squads right in front of the first three of ours”,[8] which makes it clear that the device was identical in both armies.

The battles of the Palatine phase, with the exception of White Mountain and, to a lesser extent, Stadtlohn, were essentially clashes between infantry (Catholic) and cavalry (Protestant) . The foot soldiers of the various armies hired by Frederick V were mostly made up of poorly trained peasants with poor quality equipment. In December 1622, Gabriel de Roy conveyed to Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba his negative opinion about the foot troops of Brunswick:"There are also a few infantry, but they are all scoundrels and they flee every day."[9] At Wimpfen, and especially at Fleurus, the Catholic infantry faced massive cavalry charges which they held off thanks to a deep and compact tactical device. In the second battle, Fernández de Córdoba amalgamated his tercios and regiments into three large squadrons which, if we trust Pieter Snayers' table of action, were 30 ranks deep. This is an ad hoc training to face a certain danger, since the device against the infantry was very different, which makes clear the great tactical flexibility of the Hispanic troops, in no way inferior to that of their adversaries. Imperial troops and the Catholic League were not far behind. As Peter Wilson has pointed out, in the 1620s they used formations of around 1,500 men varying in depth from 16 to 26 ranks, the first of which were made up of musketeers.[10]

Swedish innovations

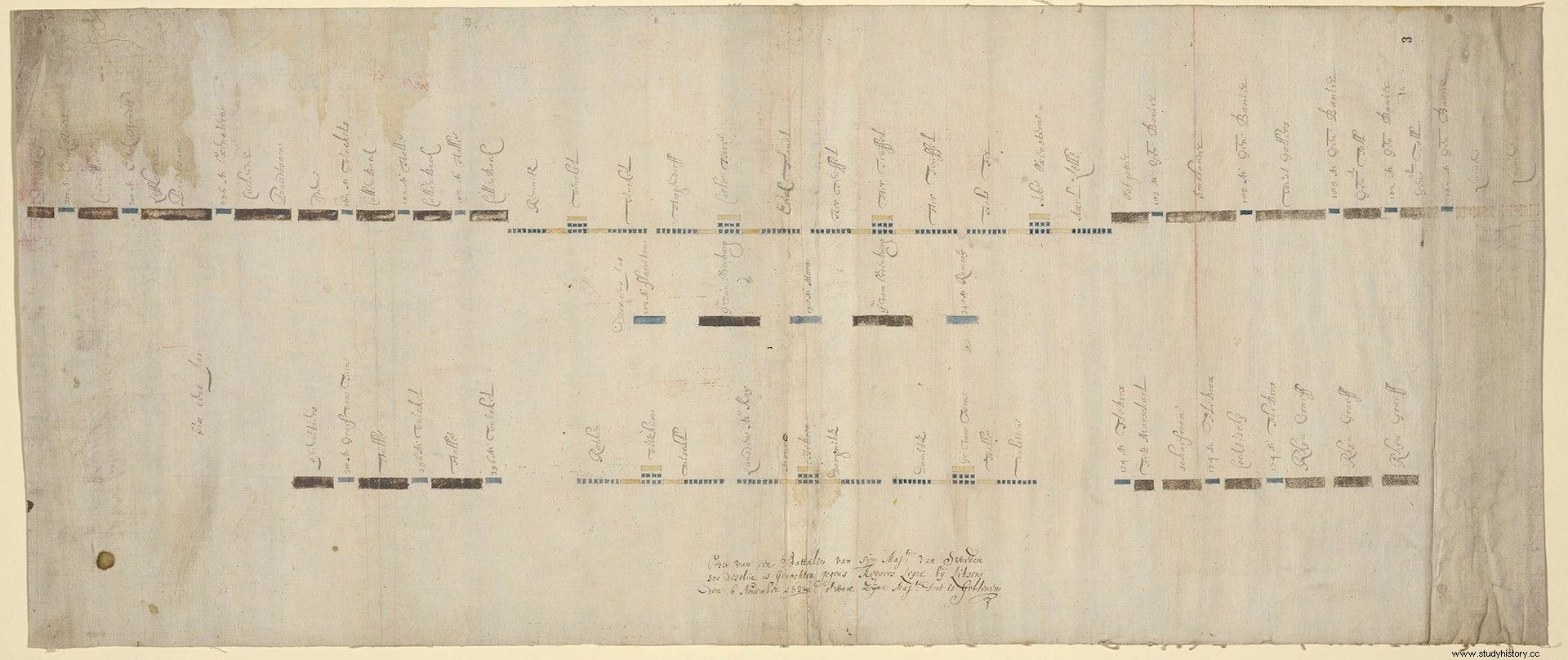

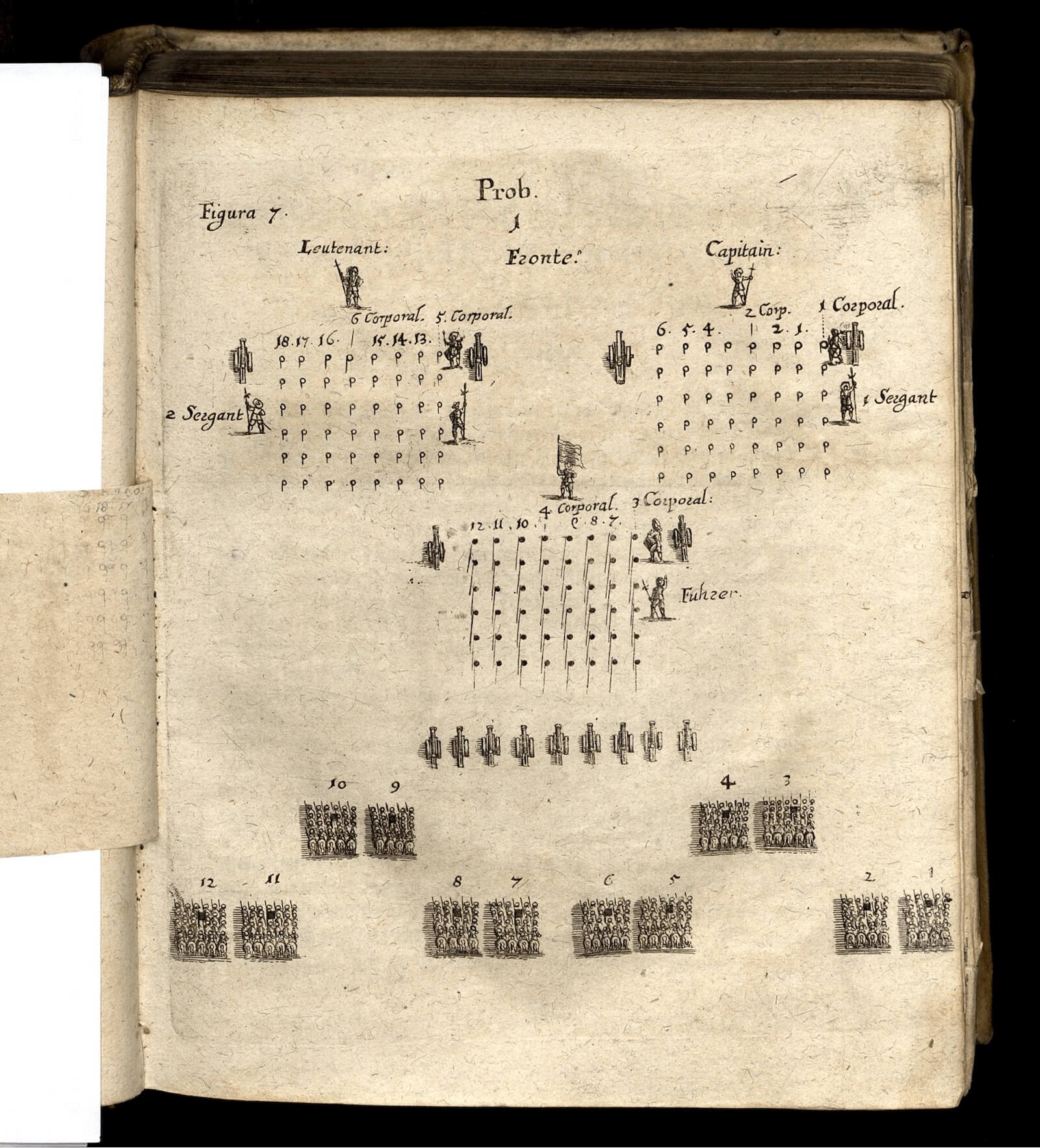

The Swedish landing in Germany in 1630 turned the tide of the war, but its consequences on the evolution of tactics have been overstated . The Swedish brigade was a large tactical unit – the Scotsman James Turner, who served in the ranks of Gustavus Adolphus, put his number at 1,800 men:600 pikemen and 1,200 musketeers.[11] The proportion is similar to that of the Hispanic and imperial troops; the big difference comes from the fact that the Swedish brigade did not deploy the pikemen in a single block but in three, in the shape of an arrowhead, or – much less frequently – in four, in the shape of a rhombus.[12] The tactical subdivisions were part of a whole and had to function in unison. These were not, as in the Dutch case, separate battalions, and contemporary observers perceived the brigade as a fixed unit. Thus, for example, Galeazzo Gualdo Priorato refers to the brigades, when he describes the Oldendorf order of battle (1633), as full battalions, instead of breaking each one down into its tactical subdivisions as if they were independent battalions:

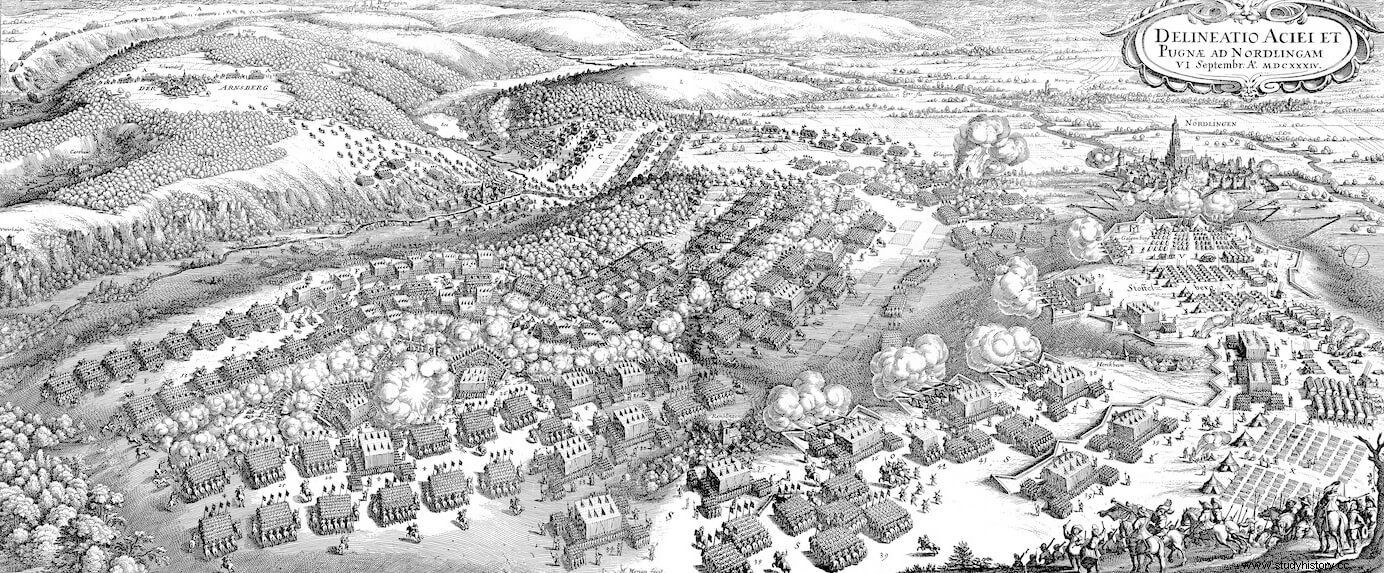

The Swedish brigade, like the Dutch system , required excellent coordination between the troops, without this implying an obvious tactical advantage. The Swedes won at Breitenfeld (1631), Oldendorf (1633) and Liegnitz (1633), but Lützen (1632) remained a draw, and were defeated at Alte Veste (1632) and Nördlingen (1634), in the latter of crushing shape . Furthermore, it cannot be said that the victories were a consequence of the tactical model. At Breitenfeld, the Imperial defeat was due rather to the risky deployment of Tilly, who formed his army in a single line, with no reserve to intervene should, as it happened, the enemy overrun one of his flanks. 14] At Oldendorf and Liegnitz, the Swedes were confronted by fledgling troops commanded by unskilled commanders. In the face of an experienced enemy, innovations such as the "Swedish salvo" or the fact of inserting sleeves of musketeers and light artillery between the cavalry squadrons were of no use.

The “Swedish salvo” was the antithesis of countermarch that we saw in the previous chapter. Instead of maintaining a sustained fire, the musketeers sought to maximize their firepower with a devastating volley in which they all fired at the same time. An English or Scottish witness to the Breitenfeld battle explains in detail how this tactic works:“The Scots formed into several corps of six or seven hundred [men] each, three ranks deep […], the most advanced, supported on knee; the second stopped higher, and the third was standing up, and shooting all in unison, they spewed so much lead on the enemy horses that their ranks were broken, and as the Swedish horses charged, the enemy was broken.”[15] The biggest drawback of the Swedish salvo is that the soldiers were left at the mercy of enemy fire and charges while they reloaded. In Nördlingen (1634), field master Martín de Idiáquez He ordered his men to lie on the ground when the Swedes opened fire, and then get up and massacre them without them being able to reply:

The Spanish troops, like the Dutch, always favored sustained fire, which, thanks to the progressive increase in the number of firearms in the companies, could keep attacks at bay. enemy battalions for hours. In Proh (1645), the Lombardy Army spent seven hours vomiting lead on the Franco-Savoyard forces, which led the Marquis de Velada, the Spanish commander, to praise the disciplined and efficient way of proceeding of his infantry, "which has been admired by all the soldiers who have seen it, and I understand that none [infantry ] of the world was able to outdo her that day when they fought for more than seven hours ardently”.[17] The debate over one or the other model had barely begun and would reach its climax in the 18th century, when the meticulous sectional fire of the British Army was measured against the French close volleys, always followed by a bayonet charge.

The idea of interspersing musketeer battalions between cavalry squadrons it was nothing new, otherwise. At Stadtlohn and Höchst, Tilly used cavalry squadrons as spearheads, accompanied by sleeves of musketeers, while the idea of interspersing infantry and cavalry formations was very old, dating back to the revival of the mounted weapon during the second half of the 16th century. . In Theorica and practice of war (1596), Bernardino de Mendoza recommended to have "the arcabucería of the sleeves and musketry in the positions where they play with more security due to their quality, or shelter given by the cavalry and squads, under which one comes to get a great effect, which is to be able to play with continuous movement, if the arquebusier is right-handed, offending the enemy”.[18] Ludovico Melzi, lieutenant general of the Flanders and Brabant cavalry, is even more explicit in his Regole militari sopra il governo e servitio particolare della cavalleria (1611):"It is found by experience to be a very profitable thing to intermingle sometimes, according to the occurrences and the need, the troops of horses with some sleeves of musketry, when the enemy is superior in cavalry".[19] The error of the Count of Fontaine in Rocroi (1643) of not reinforcing the cavalry wings with sleeves of musketeers was the exception rather than the general rule. Still, this tactic drew criticism from renowned commanders and theorists such as the most brilliant of imperial generals, Raimondo Montetuccoli, who, regarding the Swedish deployment at Nördlingen, observed that:

Like other supposed Swedish innovations, that of intermingling infantry, artillery and cavalry units in deployments had very limited scope, and Gustav Horn's successor in command of the Swedish army after its capture at Nördlingen, Johan Báner, abandoned not only this tactic but also the confusing formation of the Swedish brigade in pursuit of a conventional deployment with a single block of pikes and musketeer garrisons.

Evolution of tactics in the Thirty Years War and linear warfare

In the Thirty Years' War, three factors drove a rapid evolution in the way armies arranged their units on the battlefield. As we mentioned, the rate of firearms increased steadily, causing the deep squads to lose their sense . The Walloon Charles de Bonnières, Lord of Auchy, who fought in the Netherlands and Catalonia, was blatant in expressing, in his Military art deduced from his fundamental principles (1644), that "the advantage that the larger forehead has over the smaller one is well known, since it is seen that then more weapons fight against fewer, mainly from a distance with fire."[21] Also, the long duration and the economic cost of the conflict made the size of the units decrease. The imperative to maximize firepower without moving musketry garrisons too far from the central core of pikes prevented understrength infantry units from amalgamating into massive squads as in the past. The result was the deployment in battalions of between 350 and 1,000 men, with a downward trend, with a depth of between five and ten rows.

Evolution occurred in parallel in all armies . The campaign diary of the French Armée d'Allemagne under the command of Cardinal de La Valette, in 1636, contains instructions stating that, in the event of battle, its 6,180 infantry should be divided into 13 battalions, which yields an average figure of 524 men. per battalion, ranging from 350 to 800 troops.[22] Several years later, in 1642, Marshal Trostensson's Swedish army fielded a battalion of 800 soldiers, on average, six ranks deep, while Ottavio Piccolomini's imperial infantry arrayed in battalions of 1,000 men ten ranks deep. [2. 3] Peter Wilson, for his part, notes that already at Lützen, Wallenstein deployed his infantry in battalions of a thousand soldiers, some barely seven ranks deep.[24] The Spanish case is no different from the others . In the battle of Montijo (1644), against the rebel Juan de Bragança, the Baron of Molingen formed his 3,150 infantry into “seven squadrons with seven maeses de campo, giving them all equally six rows deep.”[25] The average was 450 soldiers per battalion and, far from an exception, we can affirm that it was common in the Hispanic armies of the time, since, even when the Spanish tactical manuals detailed how to form massive and deep squads, Francisco Dávila Orejón Gastón, who served since 1637, details in Politics and military mechanics for sergeant major of the third (1669) that:

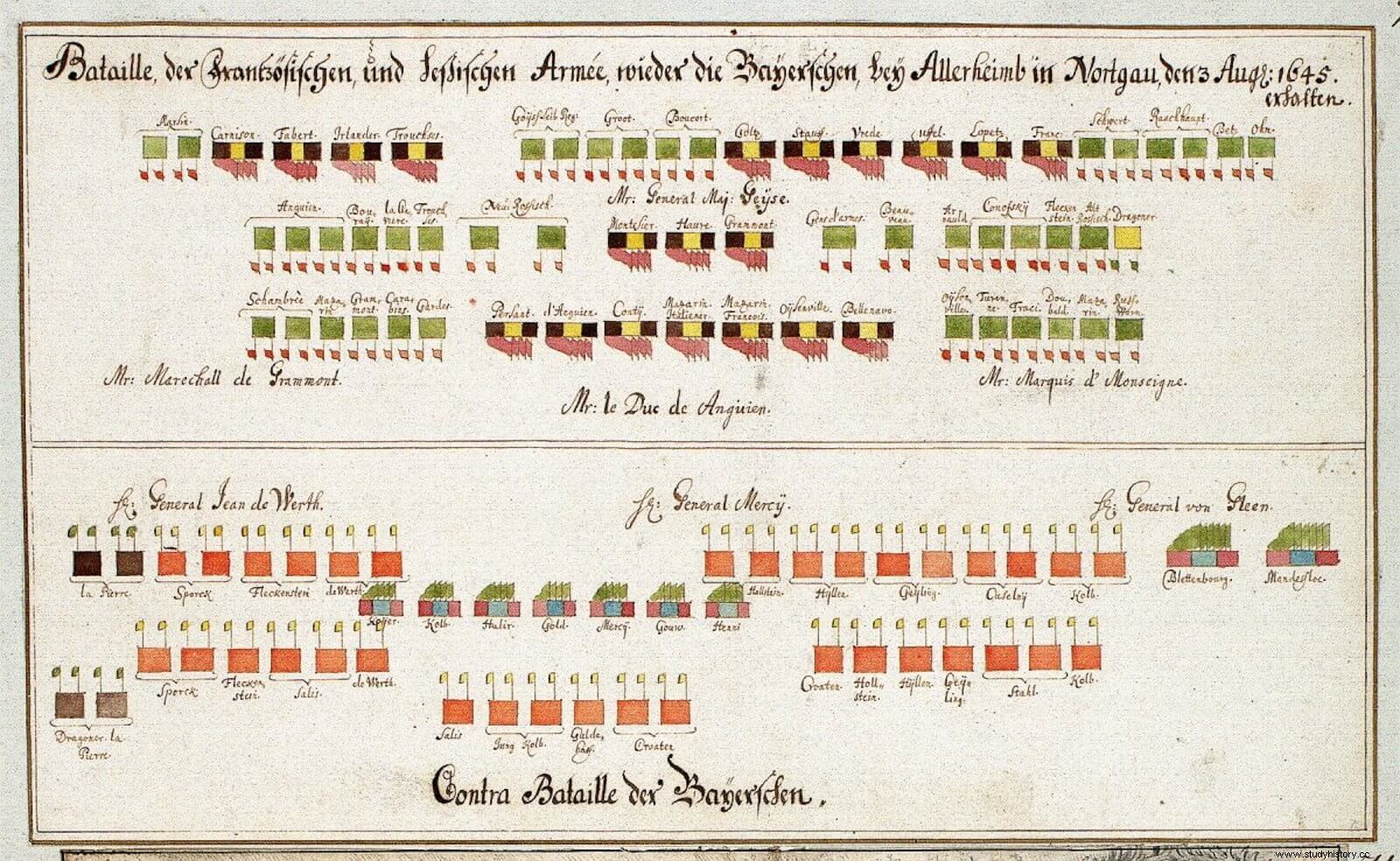

From this practice, so different from what was usual in the previous century, a reality was derived that William P. Guthrie was well aware of:by having more firearms, infantry formations gained in defensive capacity , while, by losing pikes and depth –indispensable in the clash, as we saw in the first installment of the series–, his offensive capacity decreased .[27] The main battles of the 1640s were characterized by the irrelevance of infantry combat in the center, however bloody, and were decided by cavalry clashes on the wings. Deprived of support on the flanks, the infantrymen were hopelessly surrounded and defeated. This was the case in almost all the great battles of the final phase of the Thirty Years' War:Breitenfeld (1642), Honnecourt (1642), Rocroi (1643), Jankau (1645), Mergenthein (1645), Allerheim (1645) and Lens (1648); as well as in the two key confrontations of the English Civil War, Marston Moor (1644) and Naseby (1645), and in several battles in Catalonia and Italy between the Spanish and French armies, such as those of Lérida (1644), Proh (1645 ) and Bozzolo (1647).

The third fundamental factor in the significant change that is noticeable in deployments from the 1630s on was the increase in the number of mounted forces relative to infantry . Between White Mountain and Lützen, the cavalry arm constituted between a quarter and a third of the forces in the field, while in the second battle of Breitenfeld and Jankau, the percentage of mounted troops exceeded 50%.[28] This increase in cavalry was given for reasons of a strategic nature, not tactical, since the armies thus gained mobility and could forage over greater distances. Inevitably, however, this had consequences for the tactics of the forces involved. Breitenfeld (1631) was one of the last battles in which infantry battalions and cavalry squadrons were interspersed, as had been the case –just look at the order of battle of both armies in Montaña Blanca to see that Gustavo Adolfo, far from innovating in this respect, he followed established patterns. In the 1630s, a common model was imposed that concentrated the infantry in the center and the cavalry on the flanks.[29]

The purpose of a battlefield deployment, as set out by M. de Lostelneau, Sergeant Major of the Gardes Françaises, in Le maréchal de bataille (1647), was "that all the troops be so well disposed that they can march into combat without any other impediment than the one they will receive from the enemy."[30] If the infantry formed a solid body in the center, they not only took full advantage of their firepower, but also prevented their own cavalry, put to flight by the enemy, from colliding with their own battalions and breaking them. Devices that mixed infantry and cavalry quickly gave way to the new model, while checkered or staggered formations, in which the battalions left gaps between them that covered those of the rear line, became continuous lines to facilitate the defense of the smaller and shallower battalions. The convention, in the 1630s and 1640s, was to display multiple lines, as Montecuccoli explains:

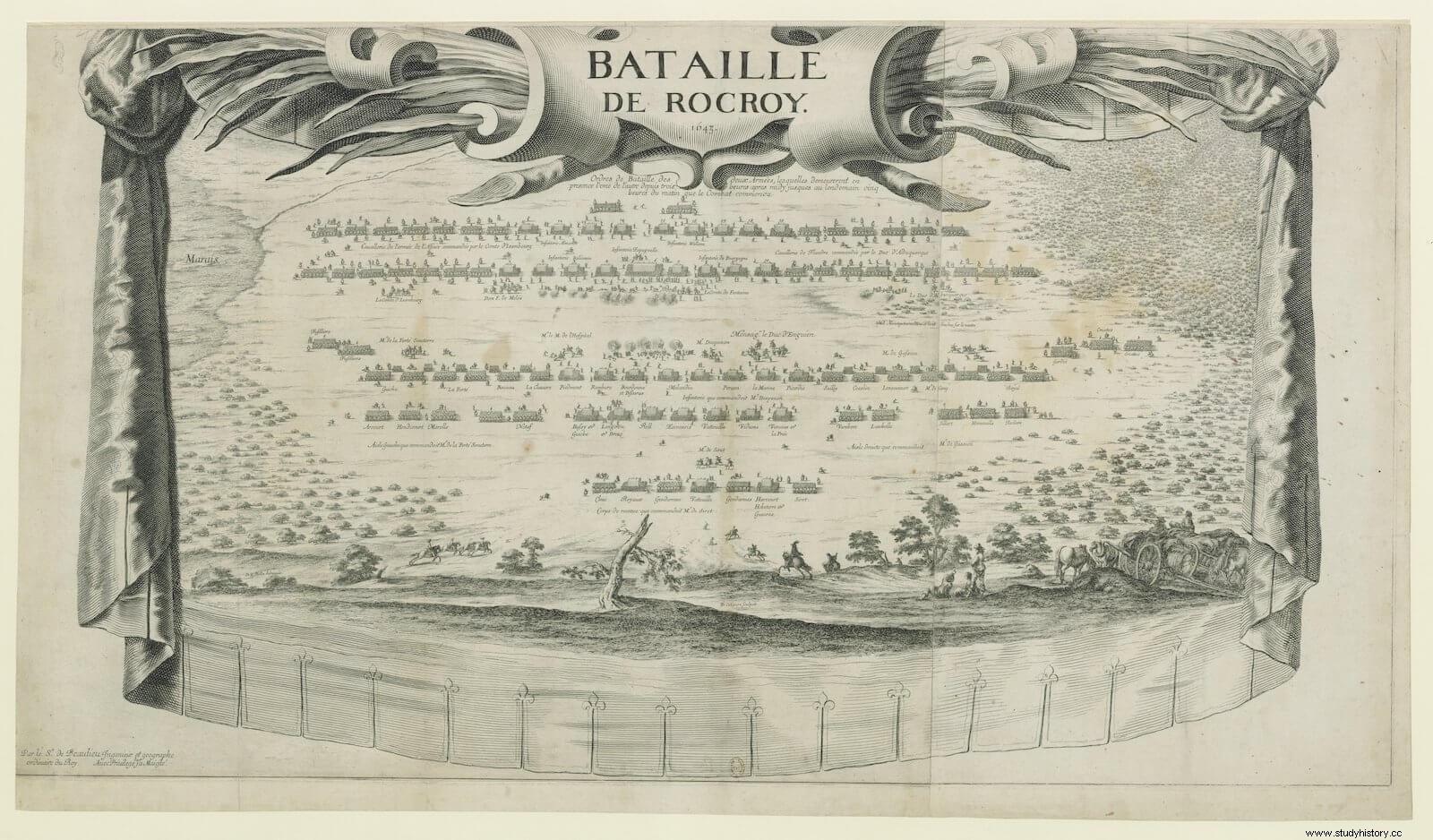

The comparison between the orders of battle Spaniards in Honnecourt and Rocroi reveals the virtues of the first and the defects of the second according to the maxims indicated. The first was raised by the experienced Jean de Beck, who had spent much of his career in the Imperial Army and had consequently taken part in many battles. The second was the work, instead, of Paul Bernard de Fontaine, who despite his many years of service had never fought in great pitched battles. Beck arranged three lines, with a strong vanguard and an equally powerful reserve in case the front lines found themselves in trouble. As the War Notices Secretary Jean-Antoine Vincart wrote:

In Rocroi, Fontaine arranged five Spanish thirds in first line, with a second line made up of three Italian, five Walloon and one Burgundian Tercios, and five German regiments as reserves, with the cavalry on the flanks. The Duke of Albuquerque, in command of the royal cavalry, harshly criticized this device, which concentrated many troops in the second line to the detriment of the reserve:

Two factors decided the victory of the French side , as many Hispanic witnesses warned. First, unlike Fontaine, Enghien had a large reserve. According to Vincart:“the battle or second row was thicker and stronger of battalions and squadrons of infantry and cavalry than the vanguard, and the reserve thicker and stronger than all”.[34] Like Tilly at Breitenfeld, the Spanish commander, Francisco de Melo, suffered from a lack of reserves when his battalions were outflanked by the French. The second factor is that the French infantry and cavalry acted in complete coordination and, in the words of Vincart:“what gave the French cavalry such an advantage was, first, that the squadrons were mixed with the infantry battalions, and being a broken squadron of cavalry withdrew behind the infantry battalion that was at his side, and there he recovered and fought again.”[35] This is not to say that the French opted for an old-fashioned deployment, with cavalry squadrons interspersed with the infantry, but rather that both forces advanced at the same time and supported each other. Despite Albuquerque's insistence on the importance of reinforcing the cavalry with sleeves of musketeers, these were of little use to the Gauls, whose cavalry, repulsed by the Spanish on both flanks, was restored thanks to the fact that their infantry battalions stopped to the Hispanic horsemen, unable to exploit their success because Fontaine did not order a general advance of the infantry that, probably, would have tilted the victory on the Spanish side. From Albuquerque:

In 1677, the Anglo-Irishman Roger Boyle, Earl of Orrey, would point out in A Treatise of the Art of War , that, “in a battle, whoever keeps in reserve a body of troops who are not led into the fight until the enemy squadrons have fought, victory seldom escapes him, and whoever has the last reserves is very likely to be victorious ”.[37] This is not the only lesson from the battles of the period, which also show that, even when the infantry assumed a more static role than in previous times, it still had to attack the opposing battalions to achieve victory.

Artillery, a secondary factor

Special mention deserves the debate on the role of artillery. It was the Swedes who carried out the main innovations in this regard, both through Gustado Adolfo, who invented a light piece that could be handled by two artillerymen and moved by a single horse, and, above all, through Lennart Torstensson, general of the king's artillery and commander of the army from 1642 to 1645. The theory dictates that these pieces should be placed between the infantry battalions and follow them in their advance. Five years before the Swedes landed in Pomerania, however, an imperial officer, the Count of Mansfeld, had devised a similar piece during the siege of Breda that was quickly adopted by Spanish and imperial forces. It's about the mansfeltina , or mansfelte , which, according to the chronicler Herman Hugo "were easily carried with two horses, and the largest with four, being necessary for each of the ancient six, ten or eighteen horses".[38] They were bronze pieces of considerable scope, with a caliber of 5 pounds, a length of 18 diameters and a weight of 8 to 9 quintals (800-1000 kg).[39] In his treatise Military Precepts:Order and Formation of Squads (1632), Miguel Pérez de Egea already speaks of placing pieces between the battalions, apart from the heavy artillery batteries, to riddle the enemy battalions before the clash occurs:“the artillery of the battalions will be fired as many times as time will give rise to the greatest diligence, being its main target, both of it and of the musketry, the squadrons of pikes and troops of cuirasses”.[40]

The light artillery tactical performance It was no different in the Catholic forces than in the Swedish ones. The difference was given by the number of pieces, since the Spanish, French, Imperial and other German forces deployed fewer pieces, and continued to favor higher caliber cannons – 12, 24 and 48 pounder. At Breitenfeld (1631), the Swedes fielded 75 cannons against 26 Imperials, and at Jankau, 60 against 27.[41] The artillery, however, was far from decisive by itself:in Nördlingen, the more numerous Swedish pieces were useless against the good position of the Catholics. Likewise, as David Parrott has pointed out, these light pieces remained static for all intents and purposes, since they could not keep up with the advance of the battalions and, on more than one occasion, Gustavo Adolfo himself considered it risky to advance them to nearby advantageous positions. the enemy.[42] Finally, it is worth noting the opinion of the Walloon Charles de Bonnières:"it is commonly said that the artillery always kills the fewest, [but] the truth is that its fury scares the most".[43] In other words, that the artillery had more of a psychological impact than a real one. In most of the battles it did not have a decisive weight and, when it did, as in Jankau, it was due to the excellent position it occupied.

Clash of Spades

The question remains whether, in the Thirty Years' War and associated conflicts, there were pick clashes between infantry battalions . The answer is a resounding yes, although with some qualifications. First of all, however, it is necessary to make clear that the pike, far from suffering contempt as a weapon, was still considered the most noble. Frenchman Jean Billon, in Les principes de l’art militaire (1638) comments:“many foreigners point out that, as for the old soldiers, two thirds of them are pikemen, and the other third, musketeers. If we talk about new soldiers, two thirds are musketeers and the rest are pikemen”.[44] These men occupied the position of honor, around the flags, and were the best equipped and most veteran. It is not surprising, then, that in 1646, at the funeral of the Earl of Essex, Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Parliament during the English Civil War until shortly before his death, the high-ranking officers of the funeral procession carried pikes instead of arquebuses.[45]

For two infantry battalions to come to the clash, both had to be made up of veteran and motivated soldiers , something that was unusual until the arrival on the scene, in the 1630s, of the Swedes and the French. For the early phases of the war, we come across testimonies from Catholic officers showing that Protestant infantry units generally broke ranks without expecting a shock. Regarding White Mountain, Louis de Haynin explains that “the Walloons [imperial vanguard unit] advanced at a good resolution up to four picas away, and since they were the first to fire and went ahead with their heads bowed, the Bohemians were frightened and they began to recede.”[46] About Stadtlohn, in his report on the battle for the infanta Isabel, governor of the Spanish Netherlands, Tilly explains that “I had an elite of musketeers pursued every so often, followed by some troops. of cavalry of my vanguard, and they have attacked them with such determination that they have broken them and put them to flight.”[47] For battles in which both armies were made up of motivated veterans, the situation was antithetical. Scotsman Robert Monro explains that, at the Battle of Frankfurt in April 1631:

About Lützen, Galeazzo Gualdo Priorato wrote that “the imperials, inflamed by the presence of their general [Wallenstein], impetuously repulsed the Swedes against the moat […] Luckily they finally crossed the pikes, and interlocking with each other, the pikes broke, and they reached for their swords.”[49] At such close range, the musketeers could not reload, so they wielded their weapons like clubs to strike with the butt, or else fought with their swords, as Lt. Col. Muschamp observes in his account of Breitenfeld:

In his account of Honnecourt, Secretary Jean- Antoine Vincart explica:“volvieron a cargar al enemigo los dichos tercios con tan buenas salvas de mosquetería, y con sus picas se arrojaron con tal ardor en los batallones franceses […] que les obligaron a retirarse a su puesto”.[51] Una situación parecida se produjo en Rocroi, donde, según el mismo autor:“luego todo el ejército francés, cargando sobre estos bizarros españoles, embistió cada batallón español con batallón de infantería y escuadrón de caballería, a los cuales, los dichos bizarros españoles, dieron tan furiosas cargas [de arcabucería], y les detuvieron con sus picas tan cerradas y tan firmes, que no les pudieron abrir ni romper”.[52] Uno año más tarde, en la victoria española en Lérida, el fuego de los cañones galos no bastó, en conjunción con el de los mosquetes, para impedir que los tercios y regimientos al mando de Felipe da Silva barriesen, pica contra pica, a un enemigo apostado en un terreno elevado. Según un anónimo observador, “marchó el ejército de frente al enemigo, aunque recibiendo mucho daño del cañón, en maravillosa orden, hasta que se dio la [orden] de que calasen las picas y embistiesen. Al regimiento de la guardia [real] tocó lo más agrio de la pelea, y el regimiento de Mota le estuvo esperando con las picas caladas y cinco piezas de artillería”.[53] Un testimonio anónimo de la batalla de Montijo, también en 1644, resulta paradigmático. Las tropas al mando del barón de Molinghem avanzaron resuelta al choque:

El estudio de los libros teóricos revela que, en las mentes de los militares de la época, la forma de combatir de la infantería no desdeñaba en absoluto el uso ofensivo de la pica . En 1632, el sargento mayor Miguel Pérez de Egea describía el modo en el que debían marchar y embestir los piqueros:

Casi cuatro décadas más tarde, el escocés James Turner, veterano del Ejército sueco y de la Guerra Civil inglesa, aconsejaba, en el tratado Pallas Armata , escrito entre 1670 y 1671, una táctica muy parecida, aunque admitía que el choque de picas ya no era tan común como antaño:

Podemos afirmar, en suma, que la importancia táctica de la infantería armada con picas apenas se resintió durante la primera mitad del siglo XVII . Los piqueros constituían el núcleo de todo batallón, su mayor defensa frente a la caballería y la punta de lanza en el momento de embestir contra las formaciones enemigas, cuando se producía el temido “choque de picas”. La creciente potencia fuego, tanto de mosquetería como de artillería, y la presencia de más unidades de caballería motivaron cambios tácticos en el despliegue de las tropas, tanto a escala regimental como en el orden de batalla general. Sin embargo, en ningún caso la pica quedó relegada a un papel secundario. No fue hasta la invención de la bayoneta, a finales de la centuria, cuando la obsolescencia tecnológica relegó la “reina de las armas” a los museos de antigüedades.

Bibliography

- Albi, J. (2017):De Pavía a Rocroi. Los tercios españoles . Madrid:Awake Ferro Editions.

- Bru, J.; Claramunt, À. (2020):Los tercios . Madrid:Awake Ferro Editions.

- Guthrie, W.; Cañete, H. A. (trad.) (2016):Batallas de la Guerra de los Treinta Años, de la Montaña Blanca a Nördlingen 1618-1635 . Málaga:Platea.

- Guthrie, W.; Cañete, H. A. (trad.) (2017):Batallas de la Guerra de los Treinta años, de Wittstock a la paz de Westfalia 1636-1648 . Málaga:Salamina.

- Parrott, D. A. (1985):“Strategy and Tactics in the Thirty Years’ War:The «Military Revolution»”, Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift , vol. 38, n.º 2, pp. 7-25.

- Picouet, P. (2019):The Armies of Philip IV of Spain 1621-1665:The Fight for European Supremacy . Warwick:Helion &Company.

Notes

[1] Valdés, F. de (1589):Espeio y deceplina militar:en el qual se trata del officio del Sargento Mayor . Bruselas:R. Velpuius, p. 17.

[2] Kelenik, J. (2000):The Military Revolution in Hungary , en Fodor, P.; Dávid, G. (eds.):Ottomans, Hungarians, and Habsburgs in Central Europe:The Military Confines in the Era of Ottoman Conquest . Leiden:BRILL, p. 144.

[3] Carnero, A. (1625):Historia de las guerras civiles que ha avido en los estados de Flandes:des del año 1559 hasta el de 1609 . Bruselas:Juan de Meerluque, p. 552

[4] Mugnai, B.; Flaherty, C. (2016):Der lange Türkenkrieg, The long turkish war (1593-1606) , vol. 2. Zanica:Soldiershop Publishing, p. 22.

[5] Novoa, M. de (1875):Historia de Felipe III, rey de España , en Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 61. Madrid:Real Academia de la Historia, pp. 185-186.

[6] AA.VV. (1621):Mercure françois:ou suite de l’histoire de nostre temps, sous le regne Auguste du tres-chrestien roy de France et de Navarre, Louys XIII , vol. 6. Paris:Estienne Richer, pp. 418-119

[7] Carta de Christian de Anhalt a Federico V, relatándole su derrota, en Wilson, P. (ed.) (2010):The Thirty Years War:A Sourcebook . London:Palgrave MacMillan, p. 64.

[8] Haynin, L. de (1869):Histoire générale des guerres de Savoie, de Bohême, du Palatinat &de Pays-Bas:1616-1627 , vol. 2. Bruxelles:Muquardt, p. 69.

[9] Copia de carta original de Gabriel de Roy a don Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, Colonia, 1 de diciembre de 1622, en (1869):Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 54. Madrid:Real Academia de la Historia, p. 356.

[10] Wilson, P. (2018). Lützen . Oxford:Oxford University Press, p. 49.

[11] Turner, J. (1683):Pallas Armata. Military Essayes of the Ancient Grecian, Roman, and Modern Art of War. Written in the years 1670 and 1671 . London:Richard Chiswell, pp. 228-229.

[12] Roberts, K. (2010):Pike and shot tactics, 1590-1660 . Oxford:Osprey Publishing, p. 49.

[13] Gualdo Priorato, G. (1641):Historia delle guerre di Ferdinando 2. e Ferdinando 3. imperatori. E del re’ Filippo 4. di Spagna. Contro Gostauo Adolfo re’ di Suetia, e Luigi 13. re’ di Francia. Successe dall’anno 1630. sino all’anno 1640 . Bologna:Giacomo Monti e Carlo Zenero, p. 170.

[14] Parrott, D. A. (1985):“Strategy and Tactics in the Thirty Years’ War:The «Military Revolution»”, Militärgeschichtliche Zeitschrift , vol. 38, n.º 2, p. 11.

[15] Anónimo (1631):Account of the battle of Leipsic published at the time , en Mathews, J. J. (ed.) (1957):Reporting the Wars . Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press, p. 264.

[16] Aedo y Gallart, D. de (1635):Viaje del Infante Cardenal Don Fernando de Austria desde 12 de Abril 1632 que salio de Madrid hasta 4. de Noviembre de 1634, que entro en la ciudad de Bruselas . Bruselas:Juan Cnobbart, p. 137.

[17] Maffi, D. (2006):“Un bastione incerto? L’essercito di Lombardia tra Filippo IV e Carlo II (1630-1700)”, en García Hernán, E.; Maffi, D. (eds.):Guerra y sociedad en la monarquía hispánica:política, estrategia y cultura en la Europa Moderna, 1500-1700 , vol. 1. Madrid:CSIC, p. 513.

[18] Mendoza, B. de (1596):Theorica y practica de guerra . Amberes:Emprenta Plantiniana, p. 117.

[19] Melzo, L. (1619):Reglas militares sobre el govierno y servicio particular de la cavalleria . Milán:Juan Baptista Bidelo, p. 90.

[20] Montecuccoli, R. (1852):Opere di Raimondo Montecuccoli . Torino:Tip. Economica, p. 232

[21] Bonnières, C. (1644):Arte militar deducida de sus principios fundamentales . Zaragoza:Hospital Real y General de Nuestra Señora de Gracia, p. 278.

[22] Fabert, A. de (1635-1639):Journal des campagnes des armées françaises en Allemagne, Pays-Bas et Italie, sous les ordres du cardinal de la Valette, pendant les années 1635 à 1639; avec plans de batailles et de forteresses . Ms. 799, Bibliotheque Sainte Genevieve, f. 34.

[23] Guthrie, W. P. (2003):The Later Thirty Years War:From the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia . London:Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 122.

[24] Wilson, op. cit ., p. 49.

[25] Anónimo (s. f.):Campañas de Cataluña y Extremadura del año de 1644 , en (1890):Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 95. Madrid:Real Academia de la Historia, p. 395.

[26] Dávila Orejón Gastón, F. (1669):Politica y mecanica militar para sargento mayor de tercio . Madrid:Julian de Paredes, p. 360.

[27] Guthrie, op. cit ., p. 122.

[28] Guthrie, op. cit ., p. 42

[29] Roberts, K. (2005):Cromwell’s War Machine:The New Model Army, 1645-1660 . Barnsley:Pen &Sword Military, p. 152.

[30] Lostelneau, S. de (1647):Le mareschal de bataille . Paris:mr. D’E. Migon, chez T. Qvinet, p. 388.

[31] Roberts, op. cit ., p. 160.

[32] Vincart, J. A. de (1642):Relación de los progressos de las armas de S. M. Cathólica el rey D. Phelippe IV, nuestro señor, governadas por el illmo. y excmo, señor D. Francisco de Mello, marqués de Torde Laguna, conde de Assumar, del Consejo de Estado de S. M., governador, lugar-thiniente y capitan general de los Estados de Flandes y Borgoña, de la campaña del año 1642 , en (1873):Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 59, p. 146.

[33] Relación de la batalla de Rocroy por el duque de Alburquerque , en Rodríguez Villa, A. (1904):“La batalla de Rocroy”, Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia, 44, pp. 511-512.

[34] Vincart, J. A. de (1643):Relación de los progressos de las armas de S. M. Cathólica el rey D. Phelippe IV, nuestro señor, governadas por el illmo. y excmo, señor D. Francisco de Mello, marqués de Torde Laguna, conde de Assumar, del Consejo de Estado de S. M., governador, lugar-thiniente y capitan general de los Estados de Flandes y Borgoña, de la campaña del año 1643 , en (1880):Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 75, p. 431

[35] Vincart, op. cit ., p. 445.

[36] Albuquerque, op. cit ., 513

[37] Boyle, R. (1677):A treatise of the art of war dedicated to the Kings Most Excellent Majesty . In the Savoy:Printed by T. N. for Henry Herringman, P. 157.

[38] Hugo, H. (1627):Sitio de Breda rendida a las armas del Rey don Phelipe IV. a la virtud de la infanta Doña Isabel, al valor del Marques Ambr. Spinola . Amberes:Ex Officina Plantiniana, p. 62.

[39] Moncada, G. R. de (1653):Discurso militar; proponense algunos inconvenientes de la milicia destos tiempos y su reparo . Valencia:Bernardo Noguès, pp. 138-139.

[40] Pérez de Egea, M. de (1632):Preceptos militares:orden y formacion de esquadrones . Madrid:Viuda de Alonso Martin, p. 138

[41] Bonney, R. (2002):The Thirty Years’ War 1618-1648 . Oxford:Osprey Publishing, p. 28.

[42] Parrott, op. cit ., pp. 15-16.

[43] Bonnières, op. cit ., p. 274.

[44] Billon, J. de (1638):Les principes de l’art militaire . Lyon:Simon Rigaud, p. 296.

[45] Roberts, op. cit ., p. 67.

[46] Haynin, op. cit . p. 175.

[47] El conde de Tilly a la infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, Stadtlohn, 7 de agosto de 1623, en Hennequin, A. C. de (1860):Tilly; ou, La guerre de trente ans de 1618 à 1632, vol. 2 Paris/Tournai:H. Casterman, p. 276.

[48] Monro, R.; Brockington, W. S. (ed.) (1999):Monro, His Expedition with the Worthy Scots Regiment Called Mac-Keys . London:Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 159.

[49] Gualdo Priorato, G. (1772):L’histoire des derniéres campagnes et négociationes de Gustave-Adolphe en Allemagne . Paris:G. Decker, p. 218.

[50] Watts, W. (1632):The Swedish Discipline, Religious, Civile, and Military . London:Printed by John Dawson for Nath, p. 24.

[51] Vincart, Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 59, p. 159.

[52] Vincart, Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 75, p. 441.

[53] Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 95, p. 380.

[54] Colección de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España , vol. 95, p. 399.

[55] Pérez de Egea, op. cit ., p. 139.

[56] Turner, op. cit ., p. 305.