The Congress of Vienna was an international conference held from September 1, 1814 to June 9, 1815 to set the framework for the new European order after the Napoleonic wars. This diplomatic meeting, in which Metternich and Talleyrand notably participated, was a major event in the history of international relations. With the ambition of reorganizing Europe after the upheavals caused by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, it favors the interests of the old authoritarian monarchies and overlooks national aspirations and the principles enshrined in the wake of revolutionary conquests. The Congress of Vienna was at the origin of several of the conflicts that appeared in the 19th century, and even in the 20th century.

The Congress of Vienna was an international conference held from September 1, 1814 to June 9, 1815 to set the framework for the new European order after the Napoleonic wars. This diplomatic meeting, in which Metternich and Talleyrand notably participated, was a major event in the history of international relations. With the ambition of reorganizing Europe after the upheavals caused by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, it favors the interests of the old authoritarian monarchies and overlooks national aspirations and the principles enshrined in the wake of revolutionary conquests. The Congress of Vienna was at the origin of several of the conflicts that appeared in the 19th century, and even in the 20th century.

The objectives of the Congress of Vienna

It all started in November 1814, when the question of the reorganization of Europe following the defeat of the 1st Empire (which will not be definitively acquired until the following June) has once again become pressing. A sign of the renewed vigor of the House of Austria, the proposed congress met in Vienna. This is notably the result of the talent and activism of Prince Metternich, former ambassador to Paris and then chancellor. The upcoming negotiations must put a definitive end to the continental troubles inherited from the French Revolution and establish a European balance.

It all started in November 1814, when the question of the reorganization of Europe following the defeat of the 1st Empire (which will not be definitively acquired until the following June) has once again become pressing. A sign of the renewed vigor of the House of Austria, the proposed congress met in Vienna. This is notably the result of the talent and activism of Prince Metternich, former ambassador to Paris and then chancellor. The upcoming negotiations must put a definitive end to the continental troubles inherited from the French Revolution and establish a European balance.

Representatives of the main powers of the time were invited to Vienna:United Kingdom, Kingdom of Prussia, Empire of Russia… as for France, it is notably represented by Charles-Maurice of Talleyrand-Périgord who, after a brilliant political career under the Empire, joined the Bourbons. Finally, other states of less importance also attend the Congress such as Sweden, the States of the Pope or the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia.

The challenges of the Congress of Vienna

It quickly becomes apparent that St-Petersburg, Berlin, Vienna and London are leading the bulk of the negotiations. Two camps seem at first sight to oppose each other. Russia and Prussia, dynamic (and relatively young) powers put forward an expansionist agenda. Austria and the United Kingdom are, for different reasons, in favor of a certain balance. This cleavage will allow French negotiators to get out of a very unfavorable situation.

The Order of Vienna will favor Austro-British options. To the requirements of balance of powers and the maintenance of the old order are sacrificed principles resulting from the French Revolution, including first and foremost, that of nationality. For the victors, the fall of Napoleon must substitute the era of the Holy Alliance for that of the Revolution. They therefore reorganized Europe, in defiance of the wishes of the peoples, according to the principles of legitimacy, restoration and solidarity of princes, tempered by concern for a European balance in favor of the great powers.

The Order of Vienna will favor Austro-British options. To the requirements of balance of powers and the maintenance of the old order are sacrificed principles resulting from the French Revolution, including first and foremost, that of nationality. For the victors, the fall of Napoleon must substitute the era of the Holy Alliance for that of the Revolution. They therefore reorganized Europe, in defiance of the wishes of the peoples, according to the principles of legitimacy, restoration and solidarity of princes, tempered by concern for a European balance in favor of the great powers.

Between balls, hunts and concerts, the representatives of the main European powers present at the congress, who had worked in select committees, met only once in plenary session, on the 9 June 1815, to ratify in a single act all the treaties signed between the participating countries.

A new European balance

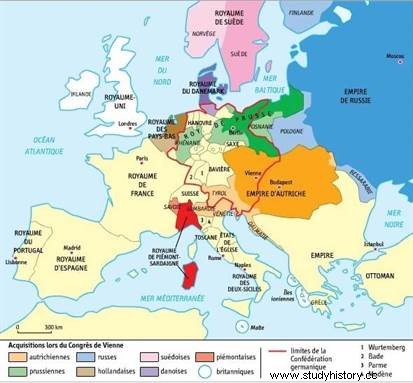

The final act of the Congress of Vienna (June 9, 1815) organized a chain of buffer states between France and the rest of Europe. Faced with a France reduced more or less to its 1791 borders, territories or states were erected which were supposed to limit any expansionism:the Kingdom of the Netherlands, made up of the former United Provinces and the former Austrian Netherlands ( Belgium); the Swiss Confederation, enlarged by four cantons (Geneva, Basle, Neuchâtel, Valais) and whose neutrality was guaranteed by the great powers; the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, which covered Nice and Savoy, expanded with the territory of the former Republic of Genoa.

Russia is expanding considerably to the East; it retained Finland and Bessarabia and annexed most of the former Grand Duchy of Warsaw, in the form of a Kingdom of Poland subject to the Tsar, although theoretically autonomous. Prussia abandoned the greater part of her former Polish domain, of which she kept only Posnania; but she received in compensation Swedish Pomerania, northern Saxony, Westphalia and most of the Rhine regions.

Russia is expanding considerably to the East; it retained Finland and Bessarabia and annexed most of the former Grand Duchy of Warsaw, in the form of a Kingdom of Poland subject to the Tsar, although theoretically autonomous. Prussia abandoned the greater part of her former Polish domain, of which she kept only Posnania; but she received in compensation Swedish Pomerania, northern Saxony, Westphalia and most of the Rhine regions.

Austria renounced Belgium but expanded on the side of Italy (annexing Lombardy and Veneto, which formed the "Lombard-Venetian Kingdom") and of the Adriatic (annexation or recovery of Illyria and Dalmatia); she recaptured the Tyrol and Salzburg from Bavaria. Germany is reorganized on the basis of a Germanic Confederation of thirty-nine states; the sovereigns of Bavaria, Wurtemberg and Saxony preserved the royal dignity which Napoleon had given them; Hanover, erected into a kingdom, returned to its sovereign, the King of England; Hamburg, Bremen, Lübeck and Frankfurt am Main were erected as free cities.

Italy, where Austrian influence was preponderant, remained divided into seven states (Papal States, Kingdom of Naples, Duchy of Tuscany, Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, Duchy of Parma, Duchy of Modena). Spain and Portugal returned to their legitimate sovereigns. Sweden retained Norway, annexed to the Treaty of Kiel. In compensation, the King of Denmark received in a personal capacity, in addition to Schleswig, which he already possessed, the duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg. England kept certain French and Dutch colonies (Guyana, Trinidad, Tobago, Saint Lucia, Mauritius, Ceylon) and important naval bases (Helgoland, Malta, Cape Town).

We owe the Congress of Vienna several other important decisions:the establishment of the principle of free navigation on the Rhine and the Meuse, the condemnation of the slave trade and slavery, and the recommendation of measures favorable to the improvement of the fate Jews.

Consequences of the Congress of Vienna

Refusing for his country such a cruel destiny, fearing for himself an exile more distant than the island of Elba, where he "reigned" from May 4, 1814 to February 26, 1815, Napoleon I attempted, during the Hundred Days (March 20-July 8, 1815), to call into question the work of the Congress of Vienna, even before it was validated by the Final Act of 9 June 1815. Consecrated on the 18th at Waterloo by the defeat of the Emperor, who embarked, on July 15, near Rochefort on the Bellerophon, this work of the Congress of Vienna established a balance of forces in Europe, which, for the essential, was not called into question before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919.

It has been said that the Congress of Vienna was the last of the 18th century. The territories were distributed there without any concern for the feelings of the people:the Polish people were divided between Russia, Austria and Prussia; the Belgians were submitted to the King of Holland; the Lombard-Venetians to the Emperor of Austria; the rest of Italy was divided in favor of reactionary rulers from the houses of Bourbon or Habsburg; the aspirations of the Germans were not satisfied by the creation of a Germanic Confederation whose links had been wanted by Metternich to be sufficiently loose in order to avoid the formation of a German unit against Austria.

In the end, the Treaty of Vienna seems to lay the foundations for a stable continental order, putting an end to post-revolutionary upheavals. Liberal ideas, condemned by almost all the powers of the time, were condemned to express themselves clandestinely, in particular through secret societies (such as the Charbonnerie). They will however return to the front of the stage barely fifteen years later, in 1830.

To go further

- The Congress of Vienna:Europe against France, 1812-1815 by Jacques-Alain de Sédouy. Perrin, 2003.

- The Congress of Vienna, by Thierry Lentz. Perrin, 2013.

- Talleyrand at the Congress of Vienna, 1814-1815 by Guglielmo Ferrero. Fallois, 1993.