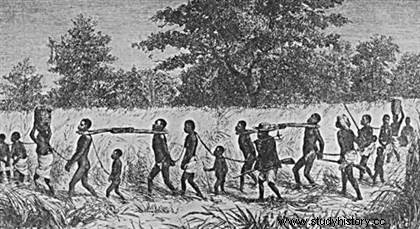

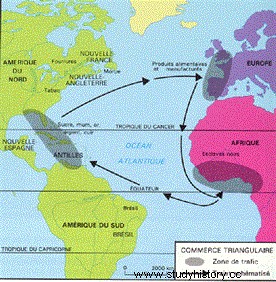

The Triangular Trade refers to the process of the slave trade from the end of the 17th century to the end of the 18th century between Europe, Africa and America (mainly the West Indies). The black slave trade represented a source of considerable profit for several European powers (in particular England, France and Portugal) and formed the basis of the economic development of the American colonies, then of the United States. Embarked on slave ships from Europe, the slaves were destined to be resold in America and the West Indies, where they were then used as labor on the plantations.

The Triangular Trade refers to the process of the slave trade from the end of the 17th century to the end of the 18th century between Europe, Africa and America (mainly the West Indies). The black slave trade represented a source of considerable profit for several European powers (in particular England, France and Portugal) and formed the basis of the economic development of the American colonies, then of the United States. Embarked on slave ships from Europe, the slaves were destined to be resold in America and the West Indies, where they were then used as labor on the plantations.

Triangular trade and slavery

For an introduction to the study of this slave trade, starting in the 15th century, before the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus, is necessary in order to place the Western slave trade in a global process, which will only end with the abolitions in the 19th century, and will have many consequences until today.

It is not always easy to find a precise definition of trafficking, and confusion with "classic" slavery is common. According to historian Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau, the slave trade can be distinguished from other forms of slavery according to five points:the slave trade requires the existence of significant logistics and supply networks, as well as an ideology for " legitimize » the company; to speak of trafficking, there must be a dissociation between the place of production and the place of use of the captive; the slave trade is perpetuated because of the high mortality of black slaves, and their demographic inability (for various reasons) “to remain in their place of importation”; the slave trade requires trade, an exchange of goods, which is different, for example, from the Arab or African raids, or the capture of slaves in Antiquity; as an extension, these important exchanges require the agreement and participation of political entities with converging interests.

Specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade (or transatlantic), it concerns the so-called “triangular” slave trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas.

The Portuguese slave trade in the 15th century

The origin of the Atlantic slave trade is generally seen in the slave trade practiced by the Portuguese during the 15th century. Mainly following the capture of Ceuta in 1415, seen as an extension of the Reconquista, a voluntarist policy of the Portuguese sovereigns, but also of the Orders of chivalry, encouraged adventurers (not only Lusitanians) to explore the western coasts of Africa. Cape Bojador was passed in 1434, Cape Verde ten years later, and Kongo reached in the 1480s, before obviously Bartolomeu Dias and then Vasco da Gama crossed the Cape of Good Hope.

The Portuguese penetrate very little inland, contenting themselves with setting up counters on the coasts. In some islands, such as the Azores, there are farmers who set up speculative crops, such as sugar cane plantations, requiring labor. The slave markets of Asia being more difficult to access because of the Ottoman conquests, the Portuguese turned to the African sovereigns with whom they came into contact as soon as their conquests in Morocco, which enabled them to bind themselves to the trafficking of slaves. trans-Saharan slaves, starting in the 1440s.

The Portuguese penetrate very little inland, contenting themselves with setting up counters on the coasts. In some islands, such as the Azores, there are farmers who set up speculative crops, such as sugar cane plantations, requiring labor. The slave markets of Asia being more difficult to access because of the Ottoman conquests, the Portuguese turned to the African sovereigns with whom they came into contact as soon as their conquests in Morocco, which enabled them to bind themselves to the trafficking of slaves. trans-Saharan slaves, starting in the 1440s.

This trade then began to slide westward, a level was reached with the development of the island of Sao Tomé in the 1480s, and the trading post of Sao Jorge de Mina, who became one of the hubs of the black slave trade . Meanwhile, other Europeans have joined this traffic, such as Genoese or Spaniards. The discovery of America, including Brazil, then the growing need for labor for the exploitation of the conquered territories, will cause the displacement of the slave trade towards the “New World”. This is how the transatlantic slave trade was born.

The beginnings of the European Atlantic slave trade (16th-17th century)

Logically, it was the powers of the Iberian Peninsula that opened the transatlantic slave trade. By various treaties, such as that of Alcaçovas (1479) and especially that of Tordesillas (1494), Portugal and Spain share the territories to be exploited. Spaniards give asientos to private companies responsible for importing African captives. The first of these contracts was signed in 1518 by Charles V.

The real turning point, which truly introduced the Americas into the slave trade, came in the second half of the 16th century, when the Atlantic slave trade became more important than the trans-Saharan slave trade. The Portuguese mainly supplied themselves in Angola then, when Portugal was annexed by Spain in 1580, the places of supply diversified, as did the origin of the beneficiaries of the asientos , who come from all over Europe. If Hispañola was obviously the first American destination in the first decades of the 16th century, successive conquests made Cartagena, then Vera Cruz, the main places of arrival of African slaves. Brazil, which developed the cultivation of sugar cane, caught up in the importation of slaves at the end of the 16th century.

From the beginning of the 17th century, the Spaniards saw the arrival of otherEuropean powers as competitors. It was first the English, who began to settle in the Caribbean, in Bermuda (1609), in Barbados (1627), then in Antigua and Montserrat (1632). This is the tobacco culture which requires a lot of labor.

From the beginning of the 17th century, the Spaniards saw the arrival of otherEuropean powers as competitors. It was first the English, who began to settle in the Caribbean, in Bermuda (1609), in Barbados (1627), then in Antigua and Montserrat (1632). This is the tobacco culture which requires a lot of labor.

The Dutch then took more and more part in the slave trade , with for example the creation in 1621 of the Dutch West India Company , which obtains the monopoly of trade with Africa and America. The Dutch, already installed in counters in Manhattan, Curaçao or Saint-Eustache, went so far as to attack the Portuguese in the early 1640s, thus breaking their monopoly on traffic from Africa.

Finally, the French entered the slave trade from the political stabilization of France, especially with Louis XIII, even if there had been some premises in Africa from the 16th century century. The colonization of Guadeloupe and Martinique, then Guyana, are the real starting point, and Cardinal Richelieu plays an important role in the process.

Here again, despite the implementation of a system of committed workers, the workforce proved to be insufficient, and the French turned to the exploitation of slaves . At the end of the 17th century, we see French slave ships sent to the African coasts to buy slaves and resell them on the American continent. The system was set up in France and, faced with European rivals, Louis XIV regulated the slave trade, in particular through the Code Noir.

The French example of triangular trade

In France, the black slave trade was prosperous from the end of the 17th century to the end of the 18th century. The triangular trade was organized between France, Africa and the West Indies. The boats left from four ports:La Rochelle, Bordeaux, Le Havre and especially Nantes (1,427 slave expeditions from 1715 to 1789) which was the world's leading slave port in the 18th century. They embarked beads, weapons, jewelry. Arriving in Africa, most often in Senegal, the slave traders exchanged their cargo for black slaves. The journey continued towards the West Indies, where nearly 5,000 blacks were landed each year in exchange for sugar, vanilla and various tropical products (coffee, cocoa, etc.), brought back to France to be sold there.

In France, the black slave trade was prosperous from the end of the 17th century to the end of the 18th century. The triangular trade was organized between France, Africa and the West Indies. The boats left from four ports:La Rochelle, Bordeaux, Le Havre and especially Nantes (1,427 slave expeditions from 1715 to 1789) which was the world's leading slave port in the 18th century. They embarked beads, weapons, jewelry. Arriving in Africa, most often in Senegal, the slave traders exchanged their cargo for black slaves. The journey continued towards the West Indies, where nearly 5,000 blacks were landed each year in exchange for sugar, vanilla and various tropical products (coffee, cocoa, etc.), brought back to France to be sold there.

The shipowner could expect 800% profit; safety on the seas was rather better ensured than in the 17th century, and dynasties of slave traders thus ensured their fortune:the Nantais Antoine Walsh armed 28 slave ships alone. The slave revolts were quite frequent on board (17 for the 427 expeditions from La Rochelle) and the mortality, depending on the case, varied around 15% per trip, which was much more than on the Dutch ships.

The heyday of triangular trade (18th century)

The triangular trade is truly in place, and is intensifying, favoring the emergence of veritable "multinationals", to which European sovereigns delegate the slave trade, often granting monopolies to certain companies.

The apogee of the Atlantic slave trade therefore occurred in the 18th century, and the competition between the Europeans was such that we witnessed real court wars> e between competing countries. The various conflicts of the century (in particular the Seven Years War) obviously influenced the place of each in the slave trade, and the English, with the development of cotton plantations in North America, became the leaders with Portugal (Brazil plays a major role in trafficking). France and Spain follow, the latter mainly because it uses a lot of asientos and delegates most of the traffic to Cuba.

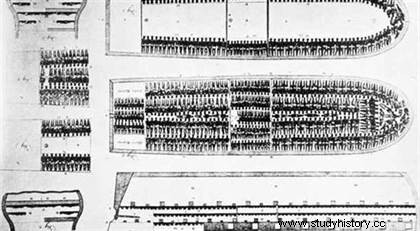

This traffic peaked also in terms of the number of deported slaves. If, in the middle of the 17th century, between 20 and 30,000 slaves were deported annually, the figure reached almost 100,000 per year at the end of the 18th century, with some drops due to European wars or the war of American independence. The loss rate during the crossing is around 15% and, if revolts are rare, they are feared by the slave traders.

This traffic peaked also in terms of the number of deported slaves. If, in the middle of the 17th century, between 20 and 30,000 slaves were deported annually, the figure reached almost 100,000 per year at the end of the 18th century, with some drops due to European wars or the war of American independence. The loss rate during the crossing is around 15% and, if revolts are rare, they are feared by the slave traders.

It was logically the period when the major European slave ports developed and grew rich. with, in England, Liverpool, Bristol or London and, in France, Nantes, Bordeaux, La Rochelle or Saint-Malo. However, a debate remains on the direct influence of the slave trade on the development of Europe. Profit rates are very variable and, while some European ship shipments can exceed 100%, others are loss-making.

The fact remains that capitalists invest in slave companies, and that the economic consequences are to be considered by broadening the spectrum. Indeed, the slave trade generates a number of highly profitable peripheral activities, and the slave trade is well integrated into the economies of European countries.

Towards the abolition of the slave trade (late 18th-19th century)

While philosophers of the late 17th and early 18th centuries had been relatively cautious, even ambiguous, about the slave trade, disputes mounted at the end of the 18th century , as did the slave revolts in the colonies.

In France, this led to the first abolition of slavery in 1793-1794, but a short-lived abolition since Napoleon reestablished the slave trade and slavery in 1802. The deposed emperor, the Congress of Vienna in 1815 again prohibited the slave trade for the French (but not only), but it continues clandestinely, and in a big way. The debates in France lasted throughout the first half of the 19th century, finally culminating in the abolition of 1848.

In the United Kingdom, the fight against slavery begins at the end of the 18th century and leads to the prohibition of the slave trade in 1807. English ships no longer transport slaves, but track down slave traders from other countries. Throughout the 19th century, however, the fight against the slave trade was a pretext used by Great Britain to promote its imperial expansion and the establishment of free trade on a global scale.

In the United Kingdom, the fight against slavery begins at the end of the 18th century and leads to the prohibition of the slave trade in 1807. English ships no longer transport slaves, but track down slave traders from other countries. Throughout the 19th century, however, the fight against the slave trade was a pretext used by Great Britain to promote its imperial expansion and the establishment of free trade on a global scale.

As for the rest of the world, the end of trafficking is progressive, and the abolitionist debates affect only very few countries like Spain or Holland. The independence of Latin American countries led to abolition in several stages, notably Chile in 1823, Venezuela in 1854, Cuba in 1886 and especially Brazil in 1888. As for the United States, it was of course the War of Secession which is decisive, and the general abolition is proclaimed from 1863. Then begins the long road for the equality of the rights…

The Atlantic slave trade thus lasted more than four centuries. Practiced mainly by the great European powers, it concerned between ten and thirteen million people, according to estimates. The other slave trade (African for example) continued (and for the most part had begun long before), and slavery, even if it took different forms, also continues.

Bibliography

- O. Pétré-Grenouilleau, The slave trade. Essay on global history, Gallimard, 2004.

- M. Dorigny, B. Gainot, Atlas of slavery, Otherwise, 2006.

- The triangular colonial trade, 18th-19th centuries, by Raymond-Marin Lemesle. PUF, 1998.

- M. Ferro (dir), The Black Book of Colonialism, Robert Laffont, 2003.