The early Mycenaean army was one of the strongest of its time in the wider Eastern Mediterranean region. His main source of strength was his infantry trained to fight in dense formation with long spears and his light shock tanks.

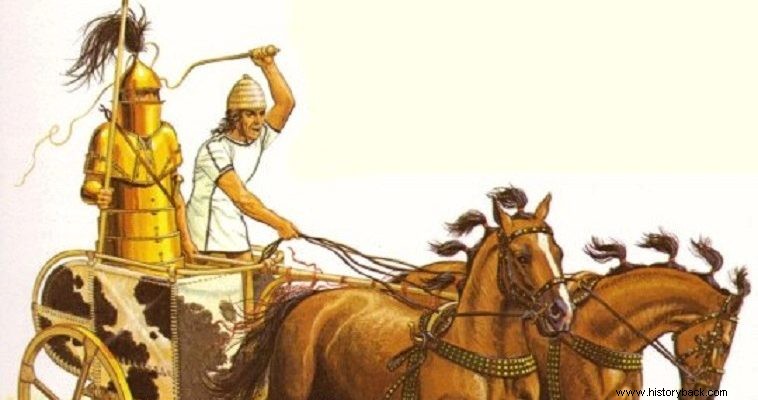

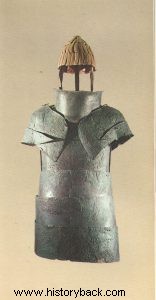

The chariots were two-wheeled, of light but sturdy construction and were usually drawn by two horses, sometimes by three. Each chariot was ridden by two men, the warrior and the charioteer . In the early Mycenaean period Epetis , the chariot warrior, wore heavy Tree-type armor , helmet, long lance (sound) and sword.

The charioteers could also carry weapons. They wore a helmet and a thick woolen tunic, which provided them with rudimentary protection from enemy projectiles. Epetis did not carry a shield . His armor was so strong and gave him such almost complete protection that it made the use of a shield unnecessary.

The tanks were lined up. The passage from the Iliad is indicative, in which the experienced old king of Pylos Nestora appears to guide the charioteers:"He commanded the horsemen first, ordering their horses to hold back and not shake the group. Let no one in chivalry and valor having conviction alone before others rush the Trojans to fight, do not retreat, for you will be more vulnerable.

"And whoever comes from his own vehicle to another should strike him with his spear, because it is much better that way. In this way the ancient cities and walls were built, having this mind and soul in their breasts" (Iliad, D 301-309).

Many useful conclusions can be drawn from this passage. It seems that maintaining the order of the formation was a matter of primary importance. Nestor exhorts the charioteers to maintain their yokes at all costs, without individual outbursts of heroism, without cowardice. All the chariots were to move in concert against the enemy and strike him with their spears, just as their fathers had successfully done in the past. In other words, it speaks of a massive, organized invasion.

Given that no oriental army of the time had a corresponding tank force or properly equipped and trained infantry to face the advance of the light but very fast Mycenaean shock tanks , it must be considered certain the deep psychological effect that their offensive against the wars had.

In that period (16th – 14th century BC) of the opponents of the Mycenaeans, only the Hittites and very few of their Syrian vassals or allies had shock chariots, that is, chariots whose mission, like the later knights, was to break the enemy line with their speed, momentum and weapons. Most Orientals and the Egyptians did not have impact chariots.

Their charioteers had as their main weapon the bow and secondarily the javelin. Also, no one brought such heavy armor similar to the Mycenaean Dendra-type armor, nor of course the terrifying spears, the 3-3.5 m long spears as experts estimate.

Mycenaean chariots were probably formed in two or more lines. Depending on the opponent, the tanks either sailed directly against him, or maneuvered and attacked the flanks of the enemy formation. The sight of the rush of hundreds of chariots, their riders literally clad in bronze, their huge spears throbbing, their men shouting, and the dust rising like a cloud behind them, must have been a most severe trial to the nervous system. of opposing pedestrians.

Considered the elite charioteers of the time, the Hittites were armed with shorter spears, although their chariots also carried a third crew member. They also used the tactic of quick selection to overthrow and destroy the opponent.

The long spears of the Greek charioteers, however, would certainly trouble them. Against the Syrian chariots, whose warriors were mainly armed with bows, the Greeks approached quickly, so as to have the smallest possible losses from the enemy's projectiles, and fought at close range, thus exploiting their superiority in melee weapons.

Rightfully so, some researchers called the Achaean charioteers knights (the word is phonetically not far from the word Epetis in use at the time). Like the Companions of Alexander and the Successors, so the Mycenaean knights marched impetuously, but not disorganized, against the enemy, with the aim of breaking him with their weight and momentum.

It is also very possible that the light infantry javelinmen, such as those depicted on the Pylos frescoes, were a special infantry division, which would have been tasked with the direct support and cover of the chariots. Similar infantry units - "chariot runners" - we know that the Egyptian Army had, in the New Kingdom period and the same role was served by the third crew member of the Hittite chariots.

But also the Greek armies of the classical era had developed special divisions of light infantry, the Amippus, which collaborated directly with the friendly cavalry. The practice was therefore not unknown and of course it was preserved even later, to the present day (mounted infantry, dragoons, motorized infantry, armored infantry).

Only in the late Mycenaean period do chariots become lighter and lose their role as shock weapons. The chariot warrior is now equipped with javelins, which he uses to strike down opponents from a distance, often leaving the chariot and fighting on foot.

In this period he wears a lighter breastplate similar to the bell shape of the geometric and archaic times and a shield. Tanks did not advance against regimental infantry unless it showed signs of a decline in morale.

The action of the tanks is now preceded by a struggle to wear down the friendly infantry. However, during this period, perhaps even earlier, the Greek cavalry, as we know it today, also began to develop. This regular use of chariots was preserved almost until the 7th century. BC

The famous brass armor discovered in Dendra. It offered absolute cover to the warrior who brought it.

Representation of a Mycenaean chariot. Casting Room Miniatures, 28mm.