The Gauls had attacked Greece, sowing terror and death. Nevertheless, they were eventually repulsed and forced to flee to Asia Minor. Crossing the Hellespont the barbarian Gauls began to plunder everything in their path. The Galatians poured out uncontrollably, destroying cities and villages. Someone had to stop them. The responsibility was assumed by the Seleucid king Antiochus I, the son of the founder of the Seleucid empire Seleucus I Nicator.

Antiochus was experienced in warfare, having fought alongside his father. However, at the time when the Gauls invaded, it had to face both the Egypt of the Ptolemies and Ariarathes of Cappadocia. Thus he could dispose of small forces against the vast bulk of the Gauls. Nevertheless he moved against them with a small army. There is no exact information about the strength of Antiochus, but it is estimated that he had no more than 20,000 men, of which half were peltasts and small men. The sarrisophores were no more than 4,000. But Antiochus also had 16 war elephants.

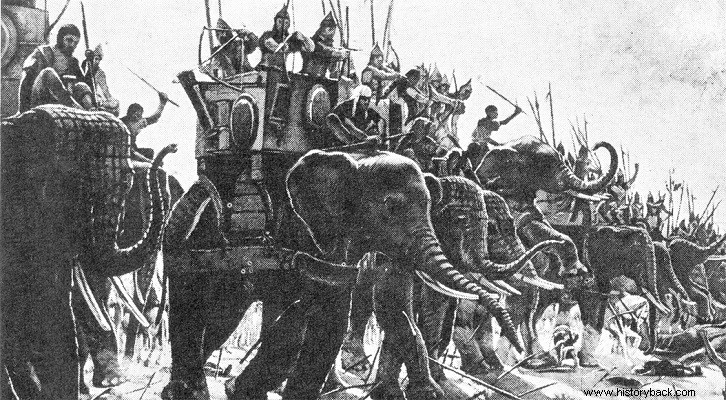

The king ordered the phalanx in the center of his line, flanking it with divisions of peltasts, right and left. He placed himself at the head of his heavy cavalry, at the right end of the line, with divisions of spearmen, javelinmen, and slingers, in front. On the left horn he sent his light cavalry, supported by light archers. With the help of the general of Theodotus, from Rhodes, Antiochus managed to hide, unknown how, his war elephants, which he divided into three divisions. One, with eight animals, lined up in the center, in front of the phalanx. Two others, with four beasts each, supported by light infantry, were placed at the two ends, so as to frighten the Galatian cavalry.

The Gauls, for their part, possessed enormous forces. According to ancient sources, their cavalry alone numbered 20,000 men. They also had 80 sickle chariots, which they sent into the center to break up the Seleucid phalanx, keeping another 160 common chariots in reserve. And if their cavalry numbered 20,000 men, their infantry would be at least twice as many, if not five times as many, as some sources state. The decisive battle was fought in 275 BC

Thus arrayed the two armies faced each other. Antiochus was waiting for the Galatians and they did not disappoint him. Calling upon their gods, they rushed forth in fierce war-yachs. The scythes raised clouds of dust as their blades flashed menacingly. So did the Galatian cavalry, charging forward to wipe out the far fewer Seleucid horsemen. But suddenly the elephants appeared. The Gauls' horses panicked. The scythe chariots stopped and turned back towards the Galatian infantry, out of control. So also the horses of the Galatian cavalry, panic-stricken, threw themselves upon their own infantry, with whom they mingled in a vast mass, unable to move.

Before long the Gallic army did not exist as an organized force. He was a mass unable to move, while thousands of his men were literally being cut to pieces by the blades of sickle chariots. Gallic footmen were cut in half, their body parts flying in the air. Thousands more were trampled by the cavalry, or by their panic-stricken colleagues, who were trying to escape. Antiochus' victory was absolute. His small army pursued the enemy mass, slaughtering thousands. The Gauls were also relentlessly hunted by the inhabitants of the areas they had plundered. For this great victory Antiochus was named by the subjects of Sotir. And to honor the elephants that gave him the victory, he minted coins and medals depicting an elephant trampling a Gallic warrior.