Elephants were domesticated by humans and used like horses as draft animals. But early on it was realized that the great physical strength of the elephant could also be used for war purposes. In India war elephants evolved into the main parts of the war machines of the rulers of the region, but also the measure of comparison of the military and economic power of each kingdom. In Gaugamela in 331 BC. Darius III's army also had 15 Indian elephants, but he did not use them in battle.

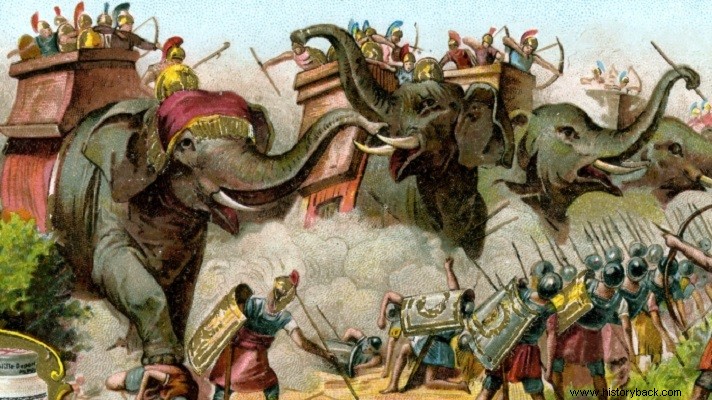

In the battle of Hydaspi in 326 BC. While fighting King Porus, Alexander was faced with 200 trained Asian war elephants. The Greeks finally neutralized the "beasts" using the sarissa and handguns. Then they realized that it was not necessary to kill an elephant. It was enough for them to injure or frighten him. The animal reacted on instinct and usually fled, trampling friend and foe indiscriminately. Despite this serious weakness, elephants as a weapon were immediately included by Alexander in the Greek army.

After his death they were used extensively in the continuous civil wars that followed. The world-historical and catalytic battle of Ipsos in 301 BC. won by allies Seleucus, Cassander and Lysimachus, thanks to 400 war elephants which they had against the 80 only of their opponents Antigonus and Demetrius Poliorkites. In this battle, Demetrius with his cavalry broke the left wing of the allied cavalry and pursued the fleeing rival horsemen. But when he tried to return to flank the enemy phalanx, he found the way blocked by the elephants of the opponents. The horses of his cavalry did not dare to approach the stout animals and thus the battle was won by the allied army.

However, during the civil wars, the Greeks accidentally discovered an antidote to the power of elephants, pigs. The Megarei were besieged during the Chremonid War (267 – 261 BC) by the troops of the Macedonian king Antigonus Gonatas. Antigonus Gonatas, like Polysperchon in 318 BC. in Megalopolis, he used elephants as living battering rams to batter down the city gates. But the Megarians anointed some pigs with tar, opened the gates and set them on fire. The unfortunate animals, being burned alive, uttered horrible screams and began to run like mad.

Antigonus' elephants, in turn, were terrified by the shouts and the flames and fled, trampling his soldiers underfoot. After that, Antigonus built a special alley, in which he placed pigs along with the elephants, so that the former could get used to the voices and smell of the latter. The same trick of syncretism was later followed by all the kings of the Hellenistic kingdoms, placing the elephants and cavalry horses together, so that the latter would cease to be afraid of the elephants. Pigs are said to have been used by Romeus against Pyrrhus, with less brilliant results.

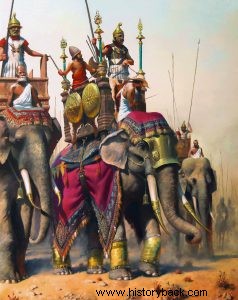

War elephants were usually used against enemy cavalry precisely because they frightened the enemy cavalry horses. In many cases, however, the entire tactical complex was formed around each elephant, as for example in the battle of Beit Zakaria when the Seleucids fought against the Maccabees organized in mixed "regiments", each of which included an elephant, 1,000 infantry and 500 cavalry. A little earlier anyway, in 190 BC. in the great battle of Magnesia, the Philian elephants and sickle chariots caused the defeat of the Seleucid army of Antiochus III, when, panicked by the blows received by the Roman and Parchment light infantry, they fled, breaking up the ranks of the Philian infantry.

The greatest Greek general of the time after Alexander, Pyrrhus, used his war elephants very wisely. In the battle of Heraklia (280 BC) Pyrrhus involved his elephants in its final stage, keeping them in reserve until then. The elephant charge did break up the already shaky Roman front, but it still almost led to disaster when an elephant was injured and began trampling friend and foe indiscriminately. The elephant's injury literally saved the Romans from total destruction. The Romans used special chariots to which they had attached large sickles against the Pyrrhic elephants.