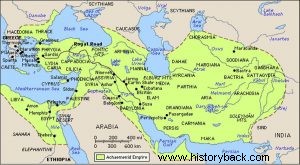

Having prevailed over his internal rivals, the Persian king Darius decided to continue the expansionist policy of his predecessors. The Persian Empire was de facto an expansionist power. Each subjugated people meant for the respective Persian king new taxes, thus income for the maintenance of the expensive state apparatus, thousands of new slaves, thus free labor, new additional military forces and new additional living space.

With this reasoning in mind, but also with the logic of ensuring a stable bridgehead on European soil, Darius decided to attack the Scythians. The various Scythian tribes then inhabited the fringes of the Persian Empire from the mouth of the Pruth, in present-day Romania and Moldavia, to present-day Afghanistan.

If, however, he simply wished to hurt the Scythians, limiting their predatory raids against his state, it would have been logical for him to attempt this through Armenia and Georgia and not through Hellespont and Thrace, as he eventually did.

On the contrary, Darius had included other factors in the upcoming campaign. Passing for the first time into Europe, he calculated to subjugate Macedonia and Thrace, securing there a firm base for further operations. His obvious goal was no other than the subjugation of the whole of Greece, since only the Greeks had remained free from all the nations neighboring the Persians.

According to Herodotus, Darius aspired to conquer all the countries from Byzantium to Lake Aral. In the early spring of 513 BC. , a Persian army of 100,000 men crossed the straits of the Bosphorus, via the floating bridge built by the Greek Mandrocles. At the same time, 600 warships sailed into the Black Sea, monitoring the army's movements from the sea.

Under the weight of the vast Persian power all cities and peoples submitted, and Darius reached the river Istro (Danube) without resistance. Only when his army crossed the river, aided by Ionian ships, did he first encounter resistance from the Thracian race of the Getae. Soon the Getae were defeated by the thousands of their opponents.

Subsequently, the sources do not mention anything about the continuation of the campaign. Herodotus only mentions that the Persians reached the river Oaros, which some identify with today's Volga. However, it is considered unlikely that they got that far. Because they were constantly harassed by the attacks of the fast Scythian horse archers and because they were marching in a completely unknown country with a non-existent road network, the Persians paid very dearly for any advances they made.

With his army suffering casualties and constantly harassed by the Scythians, Darius ordered the campaign to be abandoned and returned by the same route. This fact is an additional proof that the Persians had not reached the Volga even in their mind. Because simply if they had arrived they could have retreated by marching along the eastern shore of the Caspian and quickly found themselves in Persian land.

They would not have to make a full circle and return via Thrace and the Hellespont. Darius had left his Greek subjects as guards of the Danube bridges. It is easily understood that at the critical stage of the retreat, if the Greeks destroyed the bridges, the entire Persian army would be trapped on the eastern bank of the river and would be annihilated by the Scythians.

Herodotus even mentions that Scythian ambassadors approached the Greek guards and asked them to destroy the bridges. The head of the pro-Persian faction, however, the tyrant of Miletus Histiaeus, rejected the Scythian proposals and convinced the others to reject them as well. As he declared, any destruction of the Persians would result in the loss of power and of themselves, since they ruled as proxies of the Great King.

Only one ruler resisted the treacherous suggestions of Histiaios, Athenian by descent, ruler of Gallipoli Miltiades. Nevertheless, many Greeks of the region openly rebelled against the Persians. Byzantium, Perinthos, Chalcedon, the cities of Troas and the Oresivian Paeones, together with king Amyntas of Macedonia, rebelled against the Asians.

Darius did not bother to suppress the rebels. He left his general Megavasus, at the head of 80,000 men, to deal with the matter. He himself returned bitterly to his capital. Megavazos succeeded in bending the resistance of the Propontis cities. He even destroyed Perinthos.

However, he faced difficulties against the Macedonians and the Paeonians. He was therefore replaced by the general Otanis, who with fire and iron finally managed to force the enslaved Greeks of the North into submission. The Persians also captured Imbros and Lemnos. Although the campaign against the Scythians failed, Darius had succeeded in creating an extensive bridgehead in northern Greece.